The golden era of American organized crime unfolded not in shadowy back alleys alone, but in broad daylight—through police mugshots, courtroom photographs, and news images that captured mobsters with an audacity that would seem unthinkable today.

These men built criminal empires that shaped cities, influenced politics, and left an indelible mark on the nation’s character.

From Murder, Inc. to the Chicago Outfit, the photographs preserved from this turbulent period reveal the early days of organized crime as they truly existed—raw, violent, and far more complex than Hollywood’s romanticized portrayals.

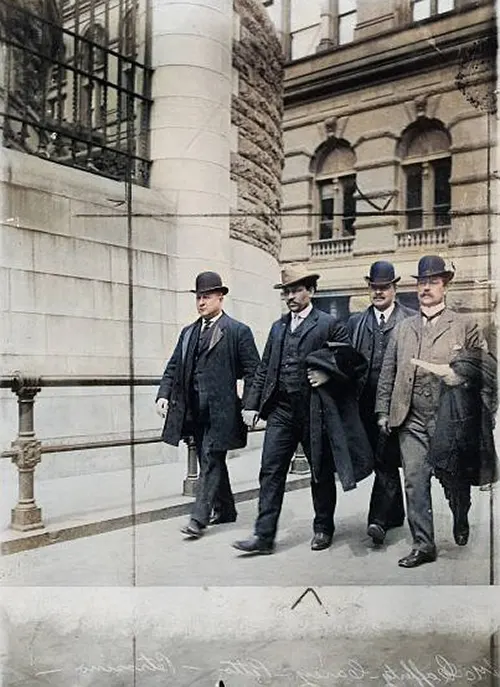

Tomasso Petto (second from left) under police escort in New York, 1903. A contract killer for the Morello organization, Petto represented the violent enforcement arm of one of America’s first established crime families.

While countless films, television series, and books have chronicled the Italian mob’s dominance in America’s criminal landscape, the authentic history of how the Mafia evolved into such a formidable force proves even more compelling than any fictional narrative.

Throughout the twentieth century, some of the era’s most influential and infamous personalities emerged from the underworld’s ranks.

These figures didn’t merely commit crimes—they fundamentally altered the trajectory of American society, leaving legacies that continue to resonate today, for better or worse.

Albert Anastasia earned his chilling nickname “Lord High Executioner” through decades of ruthless work. Rising through Joe Masseria’s operation during the 1920s, he eventually commanded Murder, Inc., the notorious contract killing enterprise that terrorized the underworld throughout the 1930s.

The American Mafia as we know it might never have existed without Salvatore Maranzano, a Sicilian immigrant who had once aspired to become a Catholic priest.

Instead of donning clerical robes, Maranzano found himself drawn to a vastly different calling.

His hunger for dominance earned him a nickname borrowed from his idol, Julius Caesar, and like that ancient Roman emperor, Maranzano possessed grand ambitions of conquest and control.

John “Sonny” Franzese maintained an extraordinary eight-decade criminal career, making him one of organized crime’s most enduring figures. Serving as underboss for New York’s Colombo family, he faced numerous arrests throughout his life and completed his final prison term at the remarkable age of 100 in 2017.

Already established as a criminal figure in Sicily, Maranzano’s move to New York following World War I transformed his career from local notoriety to underworld prominence.

He immersed himself in illegal gambling and bootlegging operations while strategically cultivating relationships with other gangsters, positioning himself for the power plays that would come.

The timing couldn’t have been more fortuitous for aspiring criminals. Prohibition had become the law of the land, and this nationwide alcohol ban created unprecedented opportunities for American mobsters to amass staggering wealth.

Raymond Patriarca dominated New England’s criminal landscape for generations. Beginning with bootlegging and armed robberies during Prohibition, he expanded his influence dramatically in the 1940s, allegedly controlling a vast network of illegal operations throughout the region.

While Maranzano methodically constructed his New York empire, a parallel criminal ecosystem flourished in Chicago, where bootleggers discovered equally lucrative prospects. Among them, one name would become synonymous with American organized crime itself: Al Capone.

Beginning as lieutenant to mobster Johnny Torrio, Capone demonstrated the ruthlessness and business acumen that would define his career.

When Torrio stepped aside in 1925, Capone inherited control of Chicago’s crime syndicate, commanding virtually all gambling, prostitution, and bootlegging operations throughout the city.

Members of the Mafia Commission gather in Cleveland, Ohio, 1928. These summit meetings allowed crime family leaders from across the country to negotiate territories, settle disputes, and coordinate their expanding criminal enterprises.

His legacy in the Windy City remains deeply contradictory. Capone wielded power as a wealthy crime boss overseeing a vast criminal network, yet he also established one of the nation’s first soup kitchens during the Great Depression’s darkest days.

This duality couldn’t mask his brutality, however—most notably demonstrated when he allegedly orchestrated the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, one of mob history’s bloodiest and most infamous executions.

The Millen-Faber gang from Massachusetts: Murton Millen, Irving Millen, and Abraham Faber. Their 1934 Needham bank robbery turned fatal when they gunned down two police officers, leading to their conviction as the first individuals found guilty of machine gun murder in Massachusetts. All three faced execution in 1935.

As Capone and his eventual successor Frank Nitti maintained their stranglehold on Chicago, New York’s criminal landscape descended into chaos. The city’s underworld had become a battleground where power-hungry leaders waged war for supremacy.

Initially, New York’s criminal enterprises operated without structure or hierarchy, creating a dangerous vacuum that demanded filling.

Two men emerged as primary contenders: Salvatore Maranzano and his rival Joe Masseria. Their competing ambitions ignited the Castellammarese War in 1930, plunging the city into violence.

Norma Brighton Millen stands beside her doomed husband Murton and his brother following their arrest. Though implicated in the deadly Needham bank robbery, she received a comparatively lenient sentence—just over a year in prison for serving as an accessory to the crime.

Both leaders commanded loyal factions within the underworld, with various gangsters aligning themselves according to personal allegiances and strategic calculations. The conflict seemed destined to continue until one side achieved complete victory.

The resolution came from an unexpected source. Charles “Lucky” Luciano, serving as Masseria’s trusted lieutenant, betrayed his boss by orchestrating his murder in 1931.

This calculated act ended the war and elevated Maranzano to the position of “boss of all bosses”—a title that inaugurated what historians would later call the Mafia’s “Golden Age.”

Frank Nitti (center) served as Al Capone’s most trusted lieutenant before ascending to lead the Chicago Outfit himself. His position as Capone’s successor made him one of the most powerful organized crime figures in American history.

Initially, Maranzano and Luciano appeared aligned in their vision for restructuring New York’s criminal enterprises.

Together they established the Five Families system, dividing the city into distinct territories controlled by separate organizations. This framework brought unprecedented order to what had been chaotic criminal competition.

The partnership proved short-lived. Power’s corrosive influence soon drove Luciano to eliminate yet another supposed ally.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel sits for questioning in 1940 following a gangland slaying in Hollywood. The charismatic mobster would later help transform Las Vegas into a gambling mecca before his own violent death in 1947.

He assembled a small assassination team that stormed into Maranzano’s office and executed him, clearing Luciano’s path to leadership of the entire Mafia network.

Luciano’s tenure brought a fundamental shift in operational philosophy. While violence remained a tool when necessary, he preferred resolving disputes between the Five Families through negotiation and compromise.

His primary objective centered on maximizing profits, and under his leadership, the Mafia’s influence expanded relentlessly, seemingly beyond anyone’s capacity to stop.

Charles Binaggio controlled Kansas City’s criminal underworld throughout much of the 1940s. His reign over the city’s illegal gambling, vice operations, and political corruption made him one of the Midwest’s most powerful crime bosses.

The empire’s invincibility proved illusory. Luciano’s deportation to Italy in 1946 created another destabilizing void.

The subsequent power struggle brought Vito Genovese to prominence, but the very event Genovese orchestrated to cement his authority would instead mark the end of the Mafia’s Golden Age, ushering in a new era of scrutiny, prosecution, and eventual decline.

Charles “Mad Dog” Gargotta served as chief enforcer for Kansas City’s crime family during the 1940s. His reputation for violence made him an essential weapon in the organization’s territorial battles and internal discipline.

In 1957, Vito Genovese summoned more than 100 fellow mob figures to the rural estate of his associate, Joseph Barbara, in Apalachin.

The meeting was intended to solidify Genovese’s authority and settle key business matters within the organization.

Their plans began to unravel when a line of luxury Cadillacs parked along a quiet country road drew the attention of New York State Police investigator Edgar Croswell, who had monitored Barbara’s activities for years. .

Louis Clementi (left), a triggerman in Al Capone’s Chicago operation, photographed alongside Philip Mangano, a member of New York’s powerful Five Families syndicate, 1920s. The image captures the era’s cross-city criminal connections.

Seeing license plates from several states and learning that large quantities of food had been delivered to the property, Croswell suspected a major gathering was underway. He quickly called for backup, set up roadblocks, and moved in.

The raid resulted in more than 60 arrests. Although many of the convictions were later overturned, the incident publicly confirmed the nationwide reach of the Mafia—contradicting earlier dismissals by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Genovese himself avoided lasting legal consequences from the meeting, but the intense publicity weakened his standing and marked a turning point for his leadership and the broader era of mob dominance

Chicago gangsters await processing in custody, 1920s. From left: Mike Bizarro, Joe Aiello, Joe Bubinello, Nick Manzello, and Joe Russio. Their arrests represented just a fraction of the city’s sprawling organized crime problem during Prohibition.

New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello (center) arrives at the city’s Masonic Building for proceedings with U.S. Immigration officials, 1961. Born in Tunisia to Sicilian parents and never naturalized, Marcello spent decades fighting deportation efforts while maintaining his criminal empire.

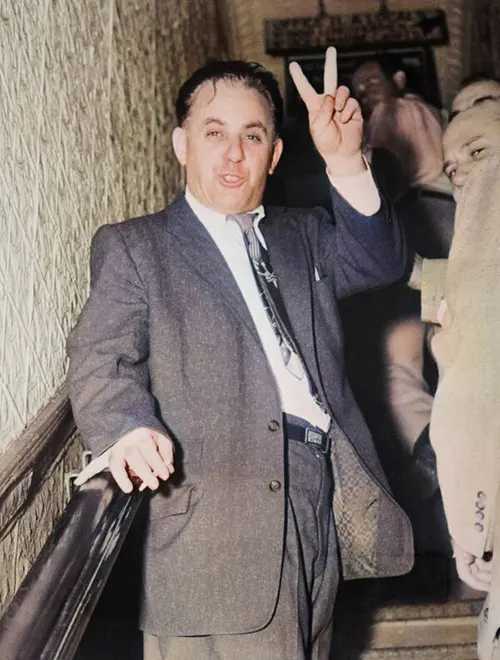

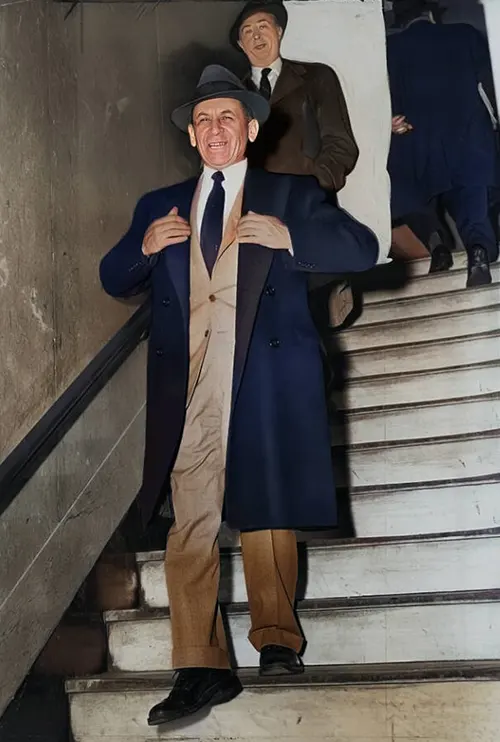

Brooklyn waterfront boss Tony Anastasia signals victory as he ascends the stairs to a pier union meeting, 1954. His control over the docks gave organized crime immense power over shipping, labor, and commerce along New York’s waterfront.

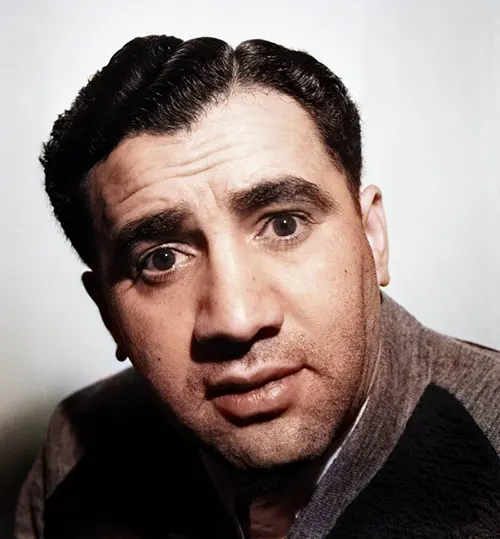

Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, one of Murder, Inc.’s most prolific contract killers, photographed at the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office in November 1941. His decision to become a government informant would expose the inner workings of organized crime’s assassination bureau.

Stephanie St. Clair, known as the “Numbers Queen,” built a lucrative gambling empire in Harlem during the 1920s. Her 1929 arrest became legendary when she retaliated against corrupt officers by testifying before a commission, resulting in the suspension of thirteen police officers who had been shaking down her operation.

Louis “Lepke” Buchalter (center) founded Murder, Inc., transforming contract killing into a sophisticated business enterprise. His organization carried out hundreds of murders on behalf of crime families across the country.

A lifelong criminal, Buchalter had already completed two prison sentences by age 22. Born and raised in New York’s Lower East Side, he entered organized crime as a teenager and never looked back.

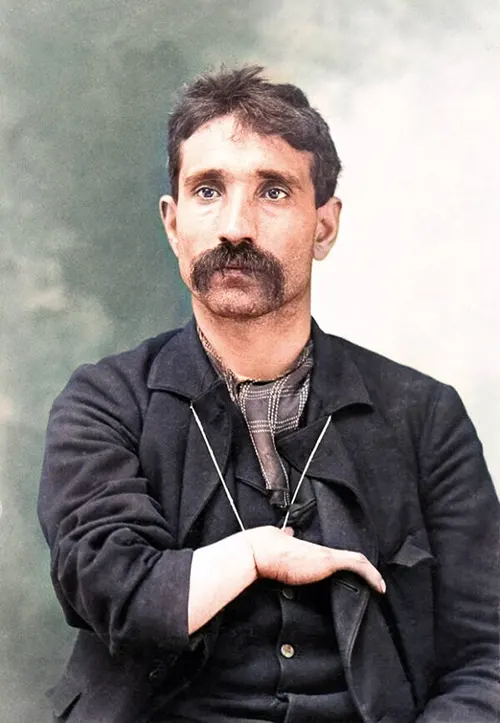

Giuseppe Morello, known as “The Clutch Hand” due to a congenital deformity of his right hand, established New York’s first major Italian crime family. Later serving as consigliere to Joe Masseria, he became an early casualty of the brutal Castellammarese War in 1930.

The Magaddino family, sometimes called the Buffalo Mafia, allegedly extended their criminal reach across Western New York, parts of Pennsylvania, and into Ontario, Canada. While some investigators claim the family’s influence waned in the late twentieth century, others suggest their operations continue in more subtle forms.

Meyer Lansky earned the title “Mob’s Accountant” through his financial brilliance and skill at concealing organized crime’s profits. Rising to prominence in early twentieth-century New York alongside Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano, Lansky became instrumental in creating the national crime syndicate during the 1930s.

Mickey Cohen ruled Los Angeles’s underworld with an iron fist while cultivating a peculiar celebrity status. Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, he controlled the city’s drug trade, prostitution, gambling, and even political machinery, all while socializing with Hollywood stars and dating actresses.

Joe Masseria dominated New York’s early organized crime landscape until ambition led to his downfall. His 1930 declaration of war against rival Salvatore Maranzano resulted in dozens of deaths before his own lieutenant, Lucky Luciano, orchestrated his assassination in 1931.

Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll carved out a violent reputation in 1920s New York through his audacious kidnapping schemes. The Irish American gangster became particularly notorious after a child was killed in the crossfire during one of his botched ransom operations.

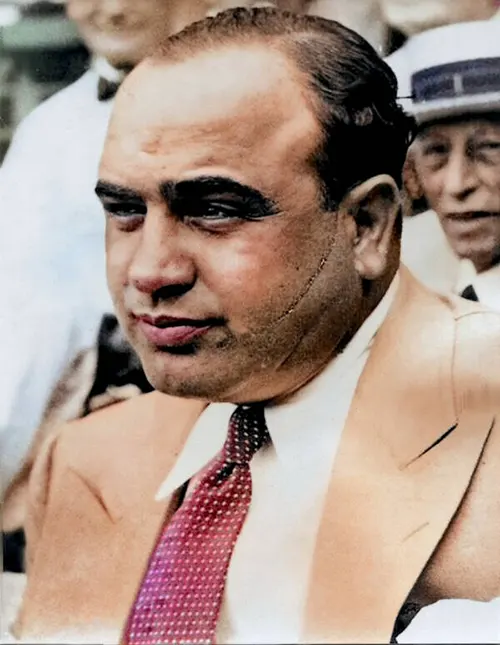

Al “Scarface” Capone despised the nickname derived from the facial scars he received in a bar fight, preferring to be called “The Big Fellow” or “Snorky.” Despite his personal preferences, the moniker stuck and became synonymous with Chicago organized crime.

Dutch Schultz awaits the jury’s decision in his 1935 tax evasion trial in New York. Though acquitted, the Jewish American gangster was murdered shortly afterward when his plan to assassinate a prosecutor reportedly angered other crime bosses who feared increased law enforcement scrutiny.

Frank Costello defied convention by testifying at a Senate hearing on organized crime in the early 1950s without invoking Fifth Amendment protections. The New York boss, known for never carrying a weapon, survived an assassination attempt and died of natural causes at 82.

Spectators shield their faces while attending Al Capone’s 1931 tax evasion trial. Their anonymity protected them from potential retaliation by Capone’s extensive network of associates and enforcers throughout Chicago.

Lucky Luciano was negotiating with producer Martin Gosch to create a film about his legendary criminal career when fate intervened. In 1962, the 65-year-old mobster suffered a fatal heart attack at a Naples airport just before authorities could arrest him in connection with an international drug trafficking operation.

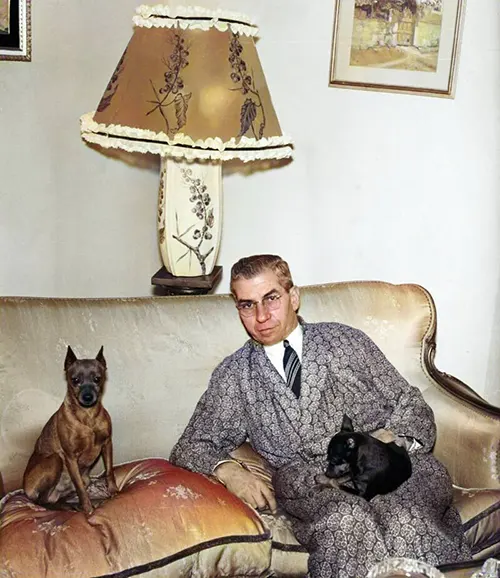

Tony “Big Tuna” Accardo maintained control of the Chicago Outfit for over four decades while spending just one night behind bars. Beginning as a low-level Capone associate, he rose to become Scarface’s bodyguard, built his own crew, and ultimately assumed command of the entire organization, earning recognition as Chicago’s true godfather.

John Adonis was an associate of Lucky Luciano, with whom he ran a bootlegging operation in Manhattan. He was later deported back to Italy, where he died.

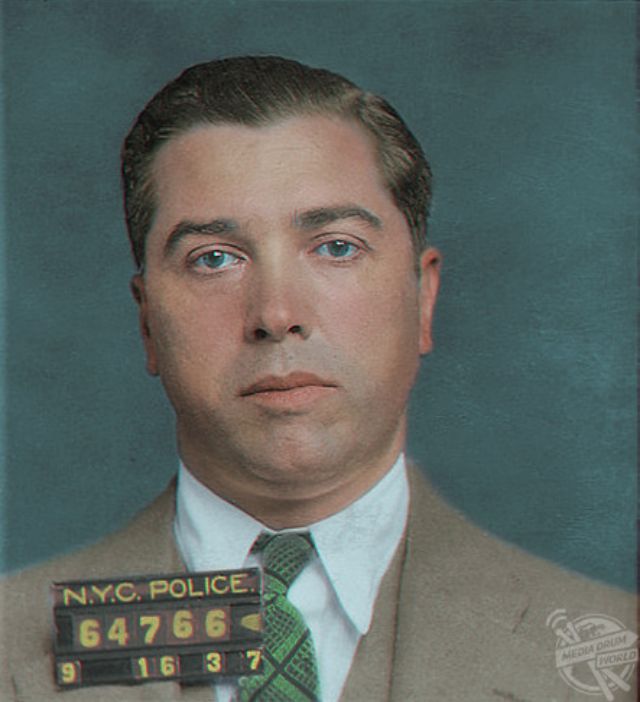

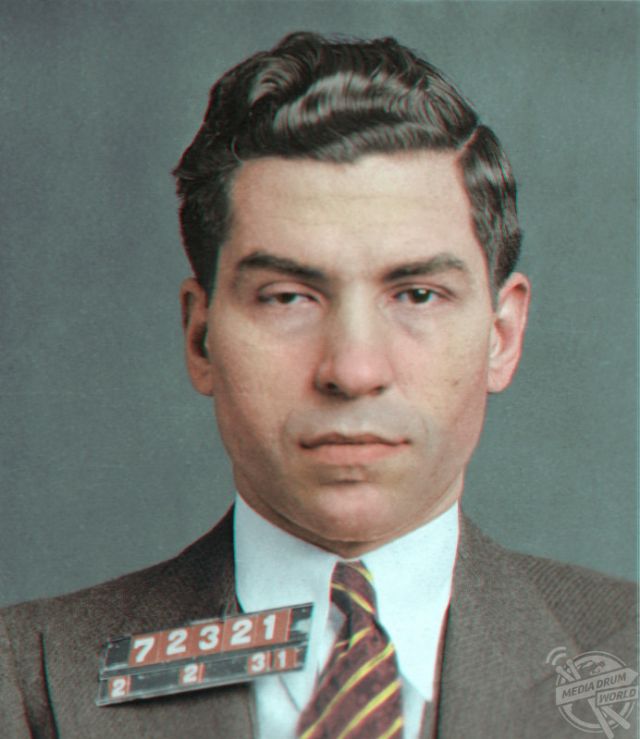

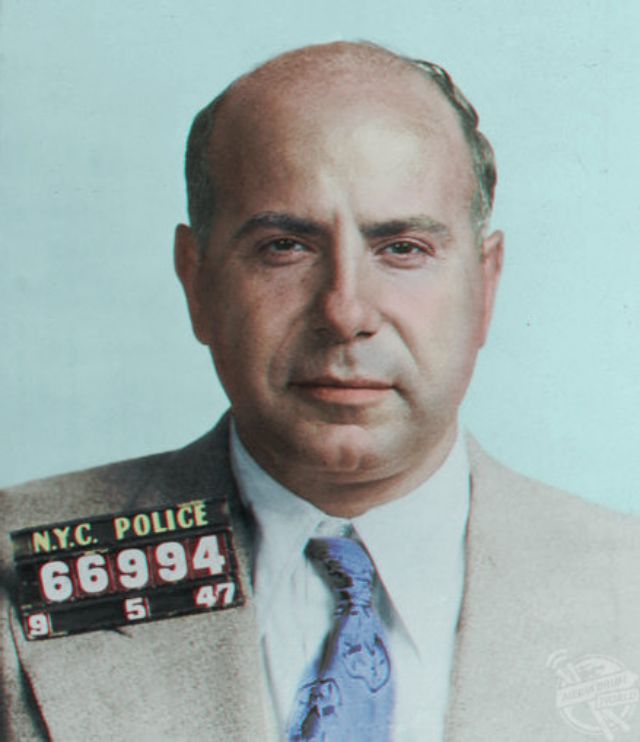

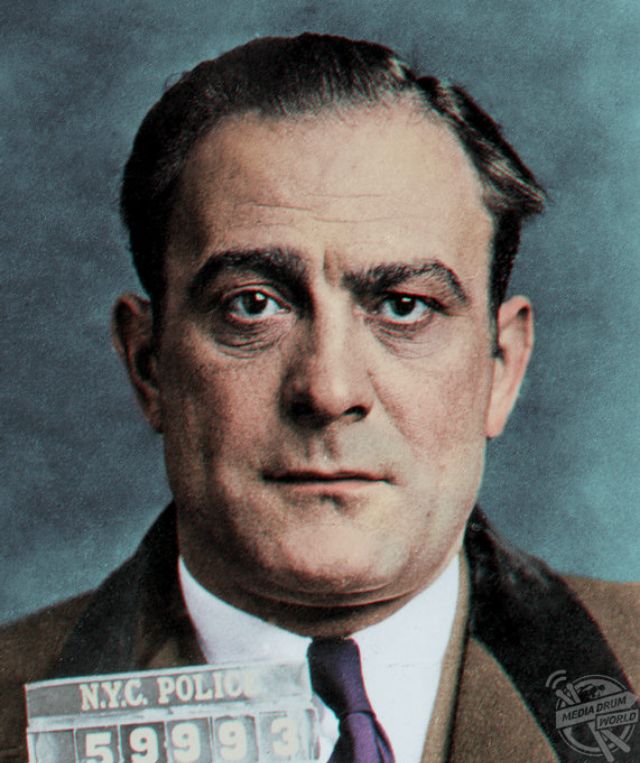

Lucky Luciano is considered the father of modern organized crime in the United States. He was also the first official boss of the modern Genovese crime family.

Carmine Galante was a feared and ambitious mobster who was once the acting boss of the Bonanno crime family.

Vito Genovese rose to power a Mafia enforcer during the 1930s and later went on to be ‘Boss of Bosses’.

Fred Barker, one of the founders of the Barker-Karpis gang, which committed numerous robberies, murders and kidnappings during the 1930s.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress / Mafia Days via Flickr).