The counterculture revolution that swept through America from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s gave birth to a youth movement that would forever alter the social landscape.

What began in the United States quickly spread across the globe, establishing pockets of resistance in cities from London to Amsterdam to Tokyo.

This subculture, known as the hippie movement, emerged from the bohemian enclaves of New York City’s Greenwich Village, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon, and Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood.

The term “hippie” itself evolved from “hipster,” originally used to describe beatniks who had migrated into these urban sanctuaries.

San Francisco writer Michael Fallon helped cement the word in the public consciousness through his printed work, though variations of the tag had surfaced in other contexts before gaining widespread media adoption.

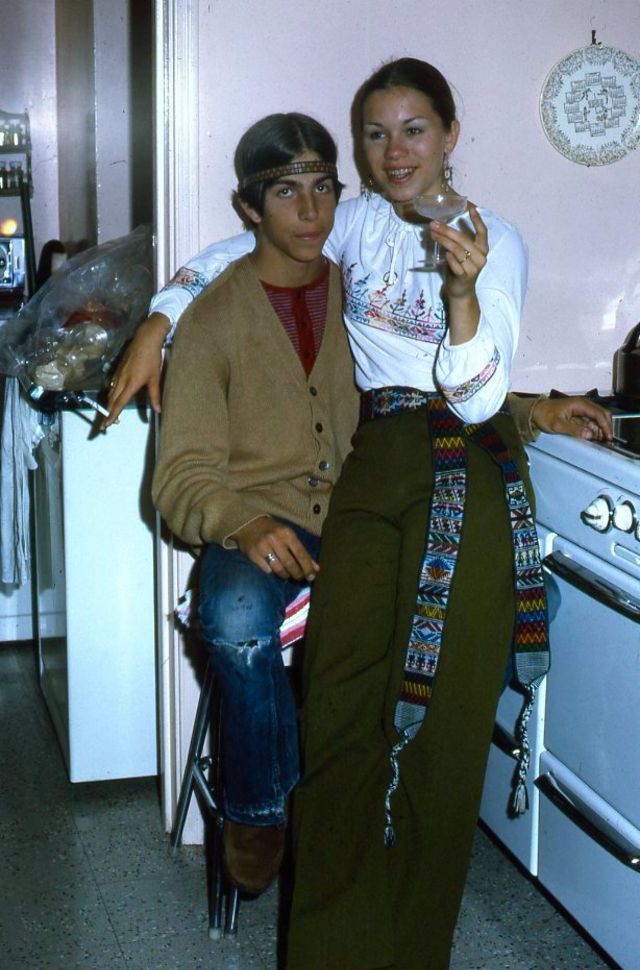

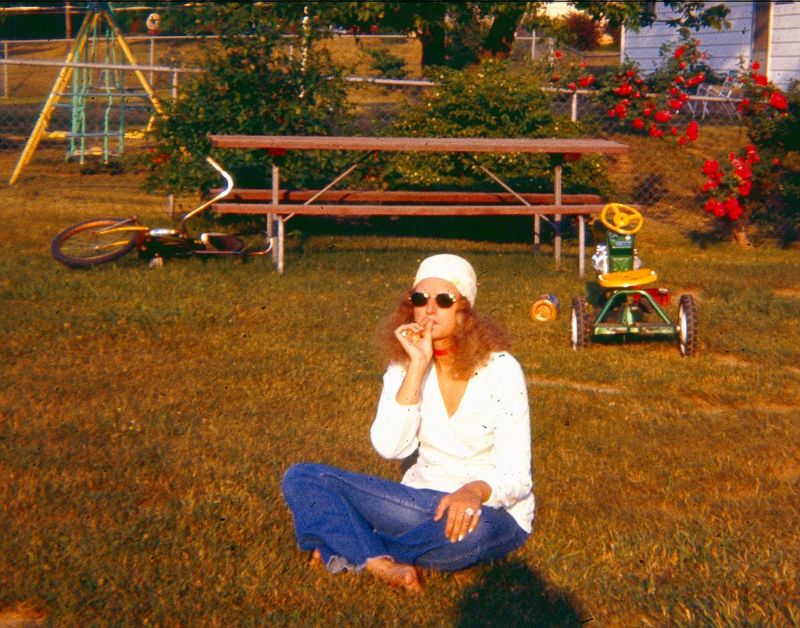

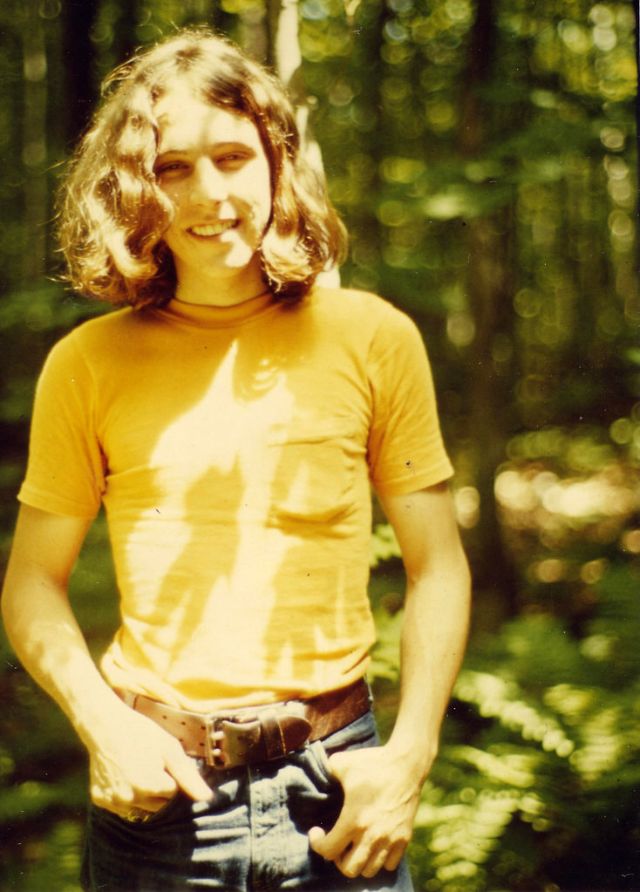

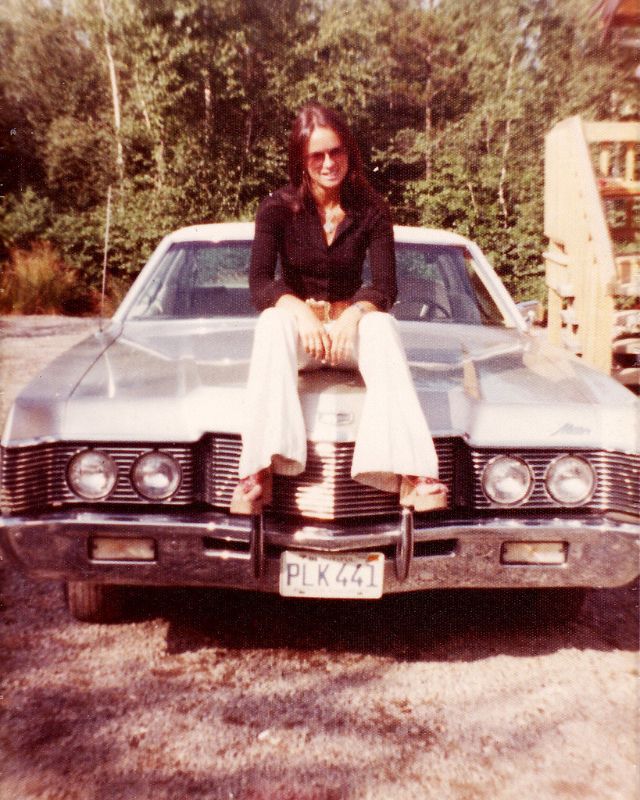

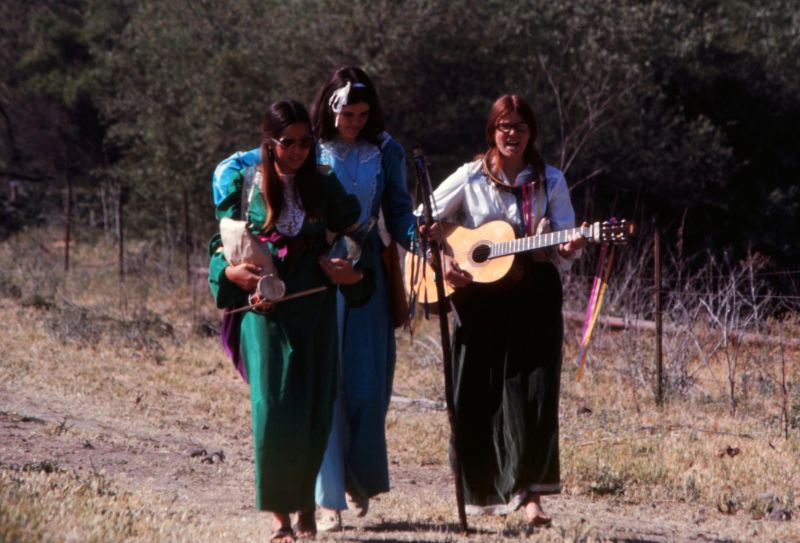

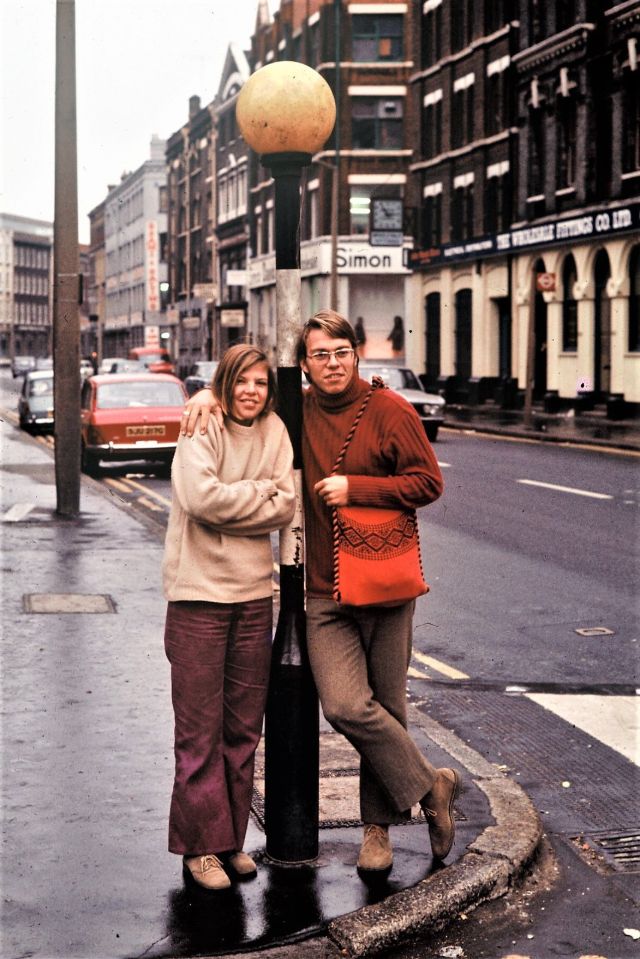

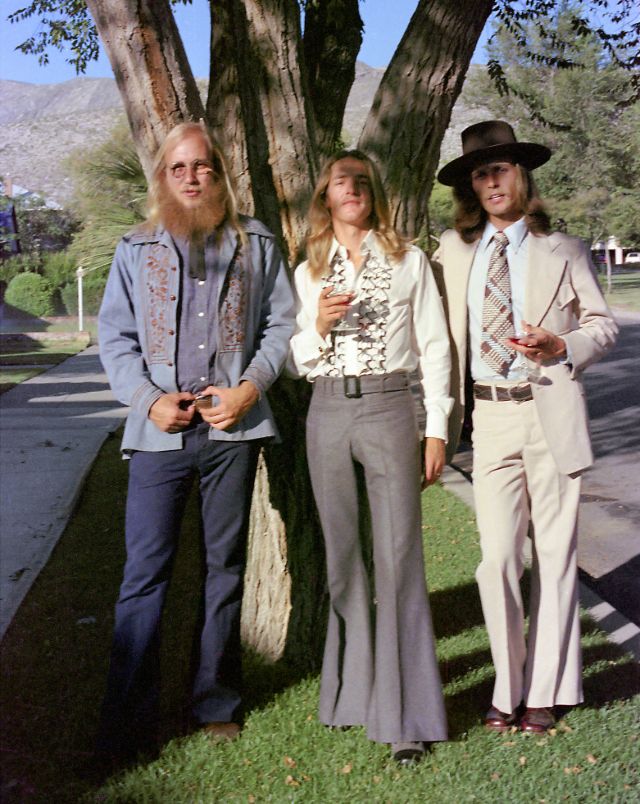

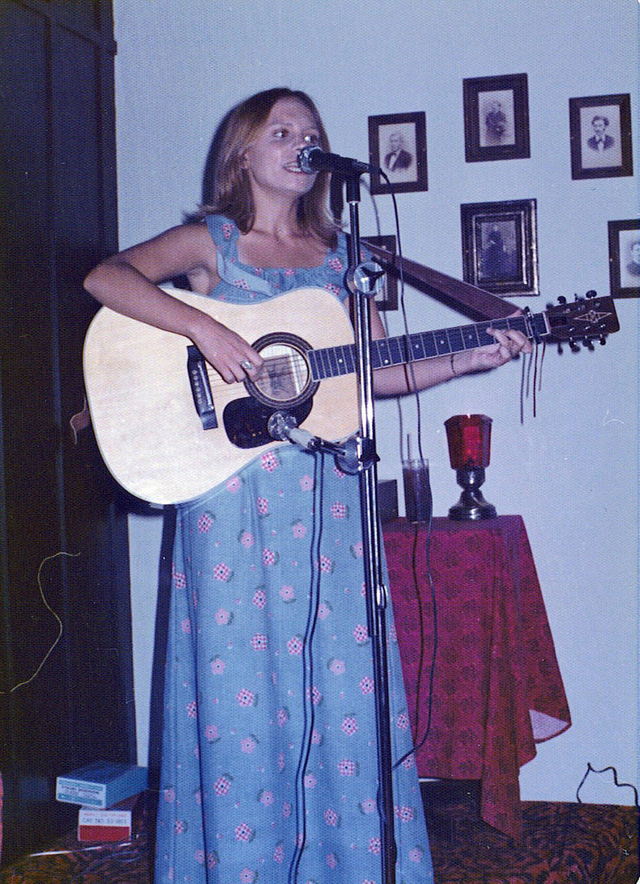

The aesthetic choices of hippies reflected their deliberate rejection of mainstream values.

Drawing inspiration from what dominant culture deemed “low” or “primitive” societies, the movement crafted a visual identity that announced its defiance.

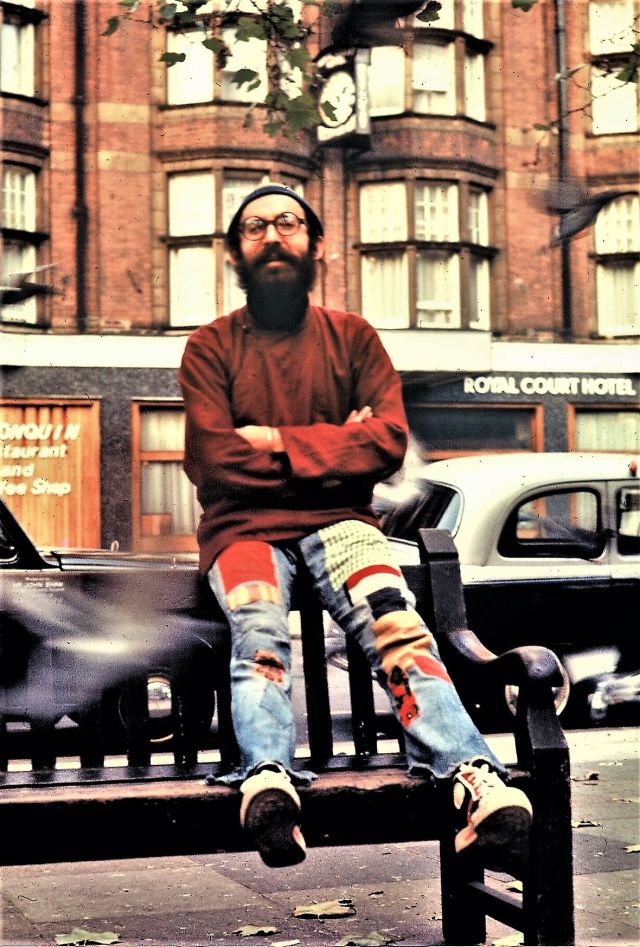

Like the Beat Generation before them and the punk movement that would follow, hippies embraced a disorderly, sometimes vagrant appearance that stood in stark opposition to conventional standards.

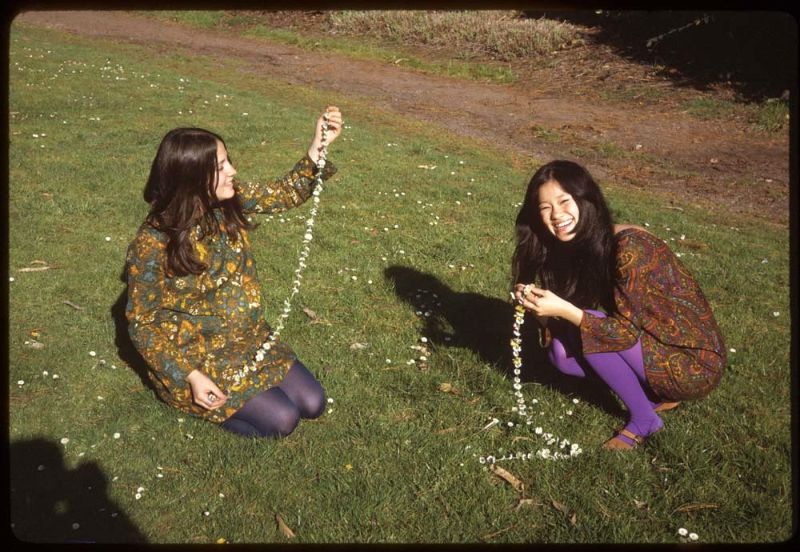

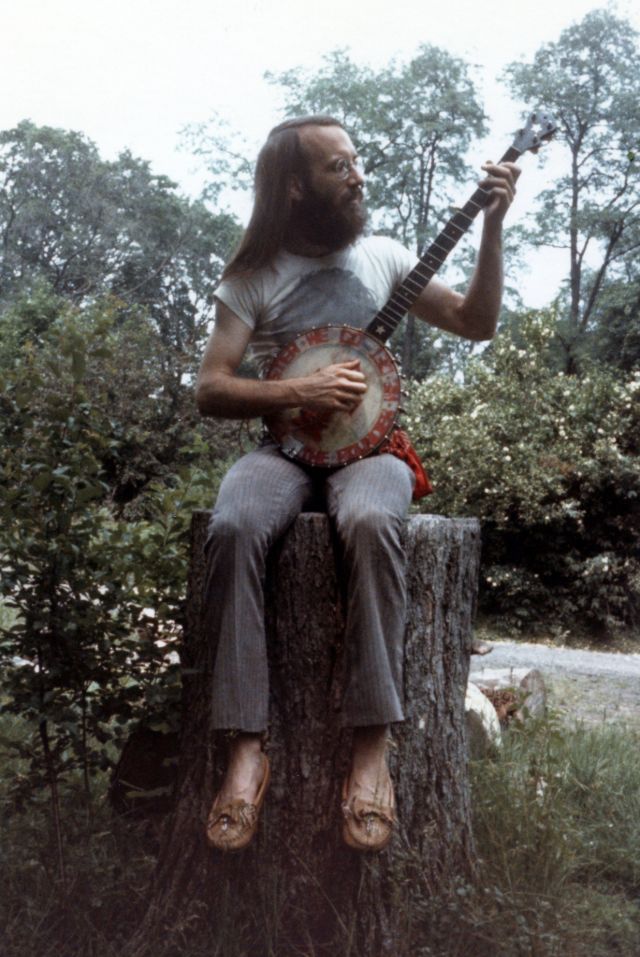

Their fashion sense became a form of cultural warfare, with vibrant, handcrafted garments replacing the manufactured uniformity of corporate America.

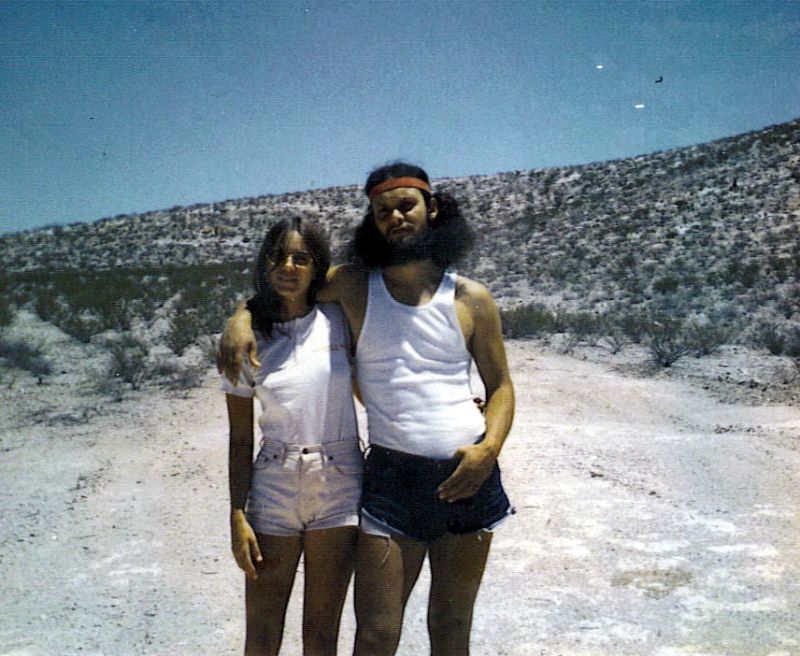

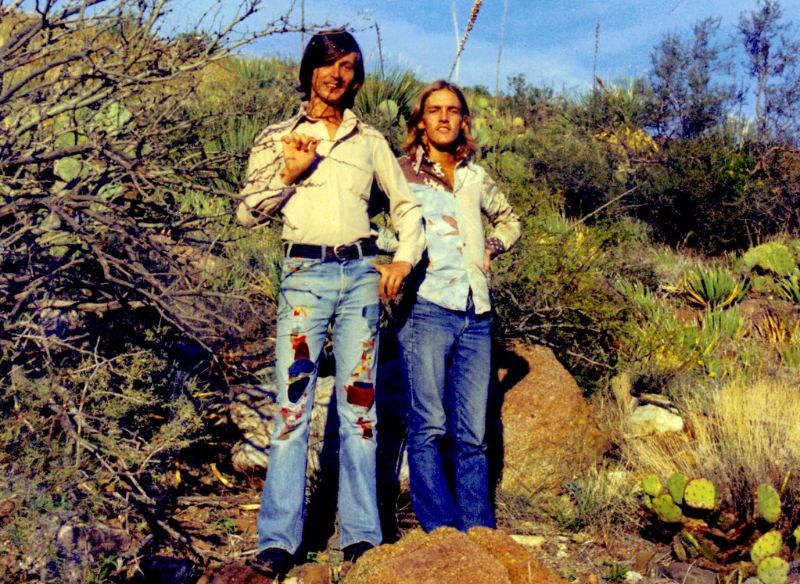

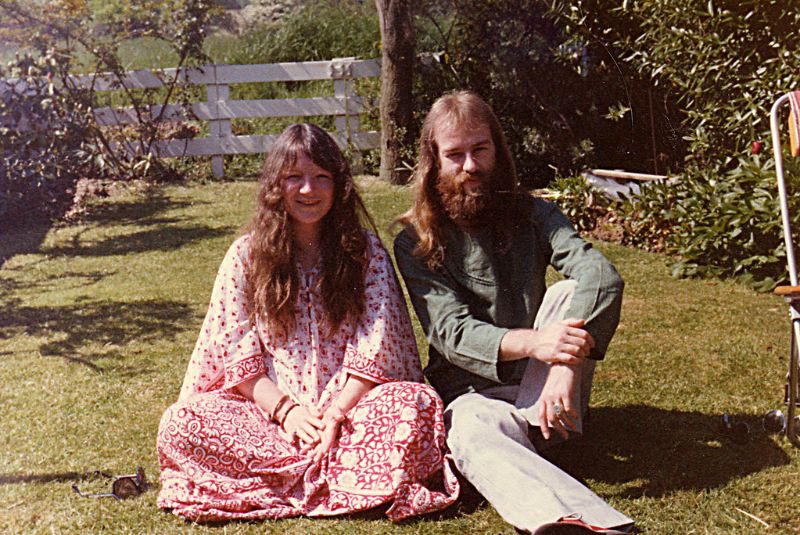

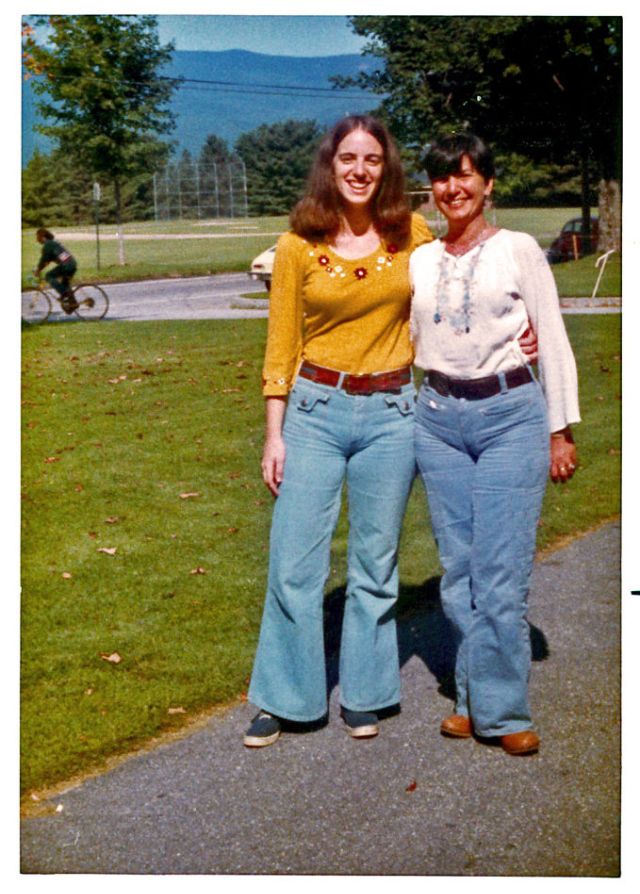

Gender boundaries, rigidly enforced in previous decades, blurred within hippie communities. Both men and women adopted denim jeans and cultivated long hair, challenging the strict grooming codes that had defined earlier generations.

Footwear became optional or minimal—sandals and moccasins were common, though many chose to go barefoot entirely, reconnecting with the earth beneath their feet.

Footwear became optional or minimal—sandals and moccasins were common, though many chose to go barefoot entirely, reconnecting with the earth beneath their feet.

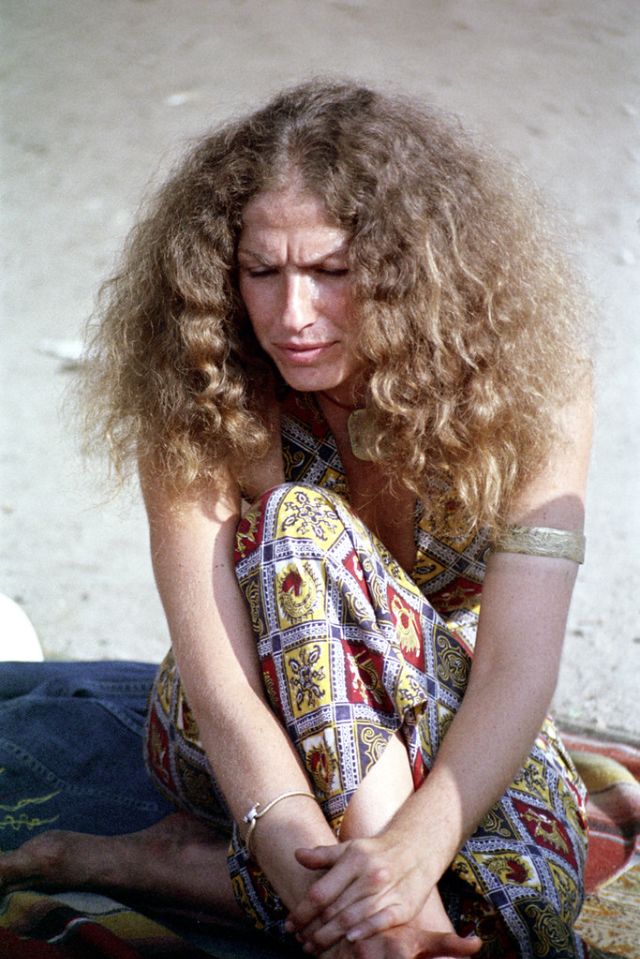

Men grew beards with pride, while women abandoned makeup and brassieres, reclaiming bodily autonomy from beauty industry dictates.

These choices weren’t merely cosmetic; they represented fundamental challenges to the prevailing gender norms of their era.

The hippie wardrobe burst with color and cultural fusion. Bell-bottom pants swayed with each step, while tie-dyed garments transformed ordinary fabric into swirling galaxies of hue.

The hippie wardrobe burst with color and cultural fusion. Bell-bottom pants swayed with each step, while tie-dyed garments transformed ordinary fabric into swirling galaxies of hue.

Vests, dashikis, peasant blouses, and flowing skirts created silhouettes that rejected the restrictive tailoring of the 1940s and 1950s.

Non-Western influences permeated hippie fashion, with Native American, Latin American, African, and Asian motifs woven into their daily dress.

This wasn’t appropriation born of ignorance but rather a conscious embrace of global perspectives that mainstream American culture had marginalized or ignored.

This wasn’t appropriation born of ignorance but rather a conscious embrace of global perspectives that mainstream American culture had marginalized or ignored.

Self-sufficiency defined hippie material culture. Rather than purchasing mass-produced clothing from department stores, many hippies sewed their own garments or scoured flea markets and second-hand shops for unique pieces.

This handcraft approach served multiple purposes: it rejected corporate consumerism, promoted individual creativity, and fostered self-reliance.

Accessories completed the look—both men and women adorned themselves with Native American jewelry, wrapped head scarves and headbands around their brows, layered long beaded necklaces over their chests, and peered through circular John Lennon-style glasses that became synonymous with the movement.

Accessories completed the look—both men and women adorned themselves with Native American jewelry, wrapped head scarves and headbands around their brows, layered long beaded necklaces over their chests, and peered through circular John Lennon-style glasses that became synonymous with the movement.

Even their living spaces embraced this aesthetic philosophy, with homes, vehicles, and personal possessions decorated in psychedelic art that transformed everyday objects into canvases of consciousness.

Mainstream society reacted to hippie attitudes toward love and sexuality with moral panic and wild exaggeration.

Mainstream society reacted to hippie attitudes toward love and sexuality with moral panic and wild exaggeration.

Stereotypes painted hippies as promiscuous hedonists engaged in wild orgies, corrupting innocent teenagers and practicing every conceivable sexual deviation.

These caricatures, while largely unfounded, reflected the broader cultural anxiety surrounding the sexual revolution unfolding simultaneously.

The hippie movement emerged during a period when long-held assumptions about sexuality, monogamy, and relationships faced unprecedented scrutiny.

The hippie movement emerged during a period when long-held assumptions about sexuality, monogamy, and relationships faced unprecedented scrutiny.

Traditional values regarding intimacy were being questioned and reimagined, and hippies stood at the forefront of this transformation, advocating for authentic connections and personal freedom over societal obligation.

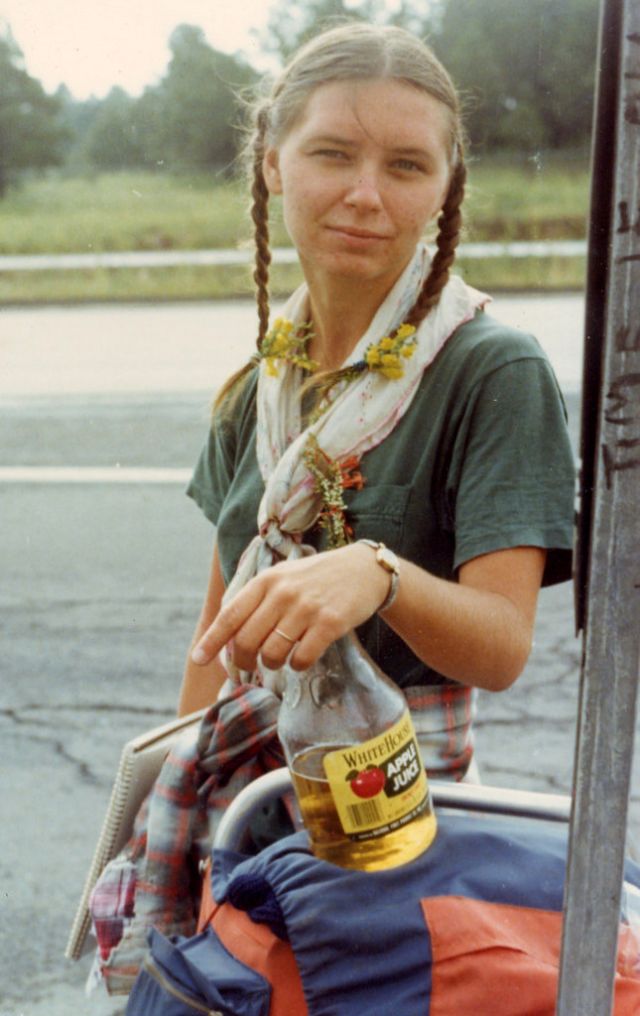

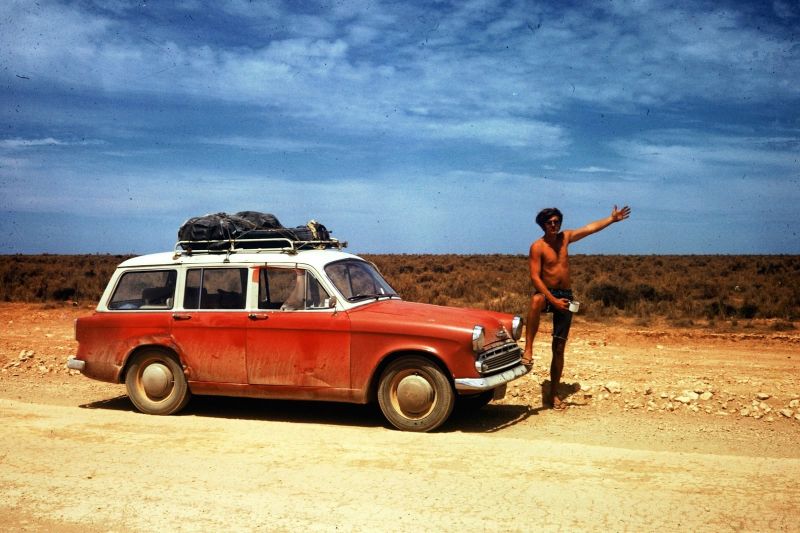

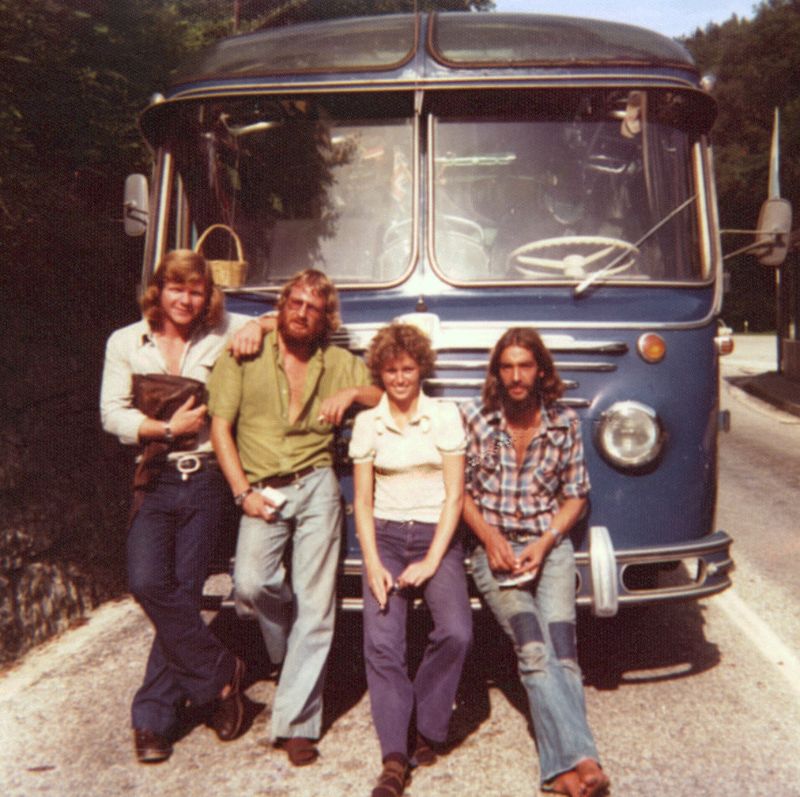

The hippie approach to movement and travel embodied their philosophy of spontaneity and communal trust. Unencumbered by material possessions, they maintained a readiness to relocate at any moment.

The hippie approach to movement and travel embodied their philosophy of spontaneity and communal trust. Unencumbered by material possessions, they maintained a readiness to relocate at any moment.

Whether gathering for a love-in on the slopes of Mount Tamalpais overlooking San Francisco Bay, protesting the Vietnam War on Berkeley’s streets, or attending one of Ken Kesey’s legendary Acid Tests, hippies remained perpetually mobile.

If the energy felt wrong or curiosity beckoned elsewhere, they simply moved on without hesitation or elaborate preparation.

Traditional travel logistics held no sway over hippie wanderers. They rejected rigid itineraries and advance planning, preferring instead to stuff a few essential items into backpacks, extend their thumbs toward passing traffic, and hitchhike to wherever the road might lead.

Traditional travel logistics held no sway over hippie wanderers. They rejected rigid itineraries and advance planning, preferring instead to stuff a few essential items into backpacks, extend their thumbs toward passing traffic, and hitchhike to wherever the road might lead.

Concerns about money, hotel reservations, or other conventional travel necessities rarely troubled them. Hippie households operated with open-door policies, welcoming overnight guests without prior arrangement or formal invitation.

Hippie households operated with open-door policies, welcoming overnight guests without prior arrangement or formal invitation.

This reciprocal hospitality created an informal network that stretched across cities and continents, enabling extraordinary freedom of movement.

Strangers became friends through shared meals and conversations; communities formed and reformed organically as travelers passed through.

People cooperated instinctively to meet collective needs, creating support systems based on mutual aid rather than monetary exchange.

People cooperated instinctively to meet collective needs, creating support systems based on mutual aid rather than monetary exchange.

This culture of generosity and spontaneous cooperation flourished throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, though it would gradually fade as the decade progressed and the movement’s idealism confronted harsher economic and social realities.

(Photo credit: spysgrandson / flickr.com/photos/18878095@N07 / Flickr / Pinterest).