The acrid smoke hung thick in dimly lit basements across America’s cities, where customers from society’s highest and lowest rungs sought refuge in clouds of vaporized opium.

These haunting photographs capture a shadowy chapter of American history when underground dens became gathering places for those chasing escape through the narcotic haze, ultimately forcing the nation to confront its first major drug crisis.

Chinese immigrants brought opium culture to American shores during the mid-1800s, with the earliest establishments appearing in San Francisco’s Chinatown between the 1840s and 1850s.

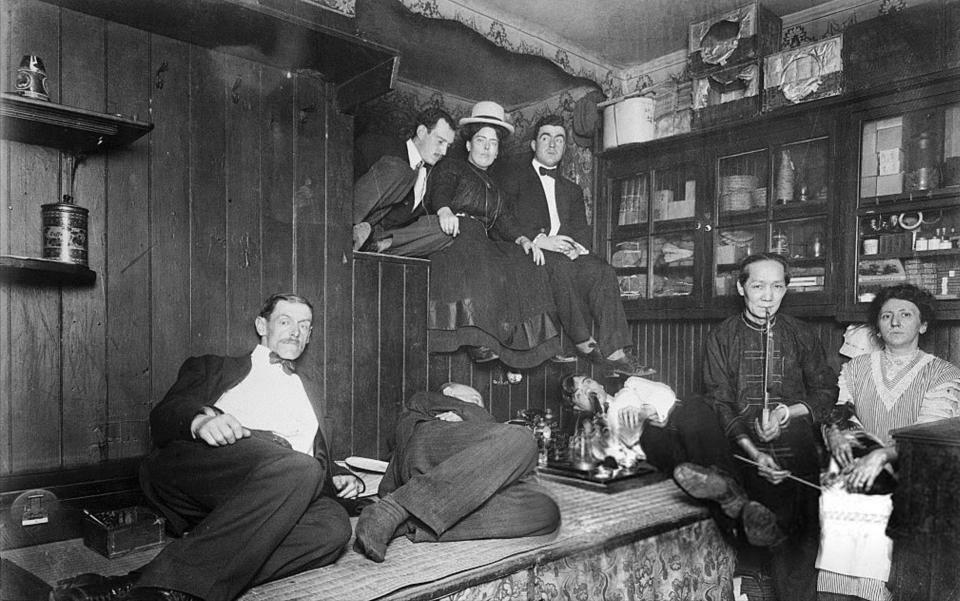

Two women and a man smoking in an opium den in Chinatown, San Francisco, circa 1890.

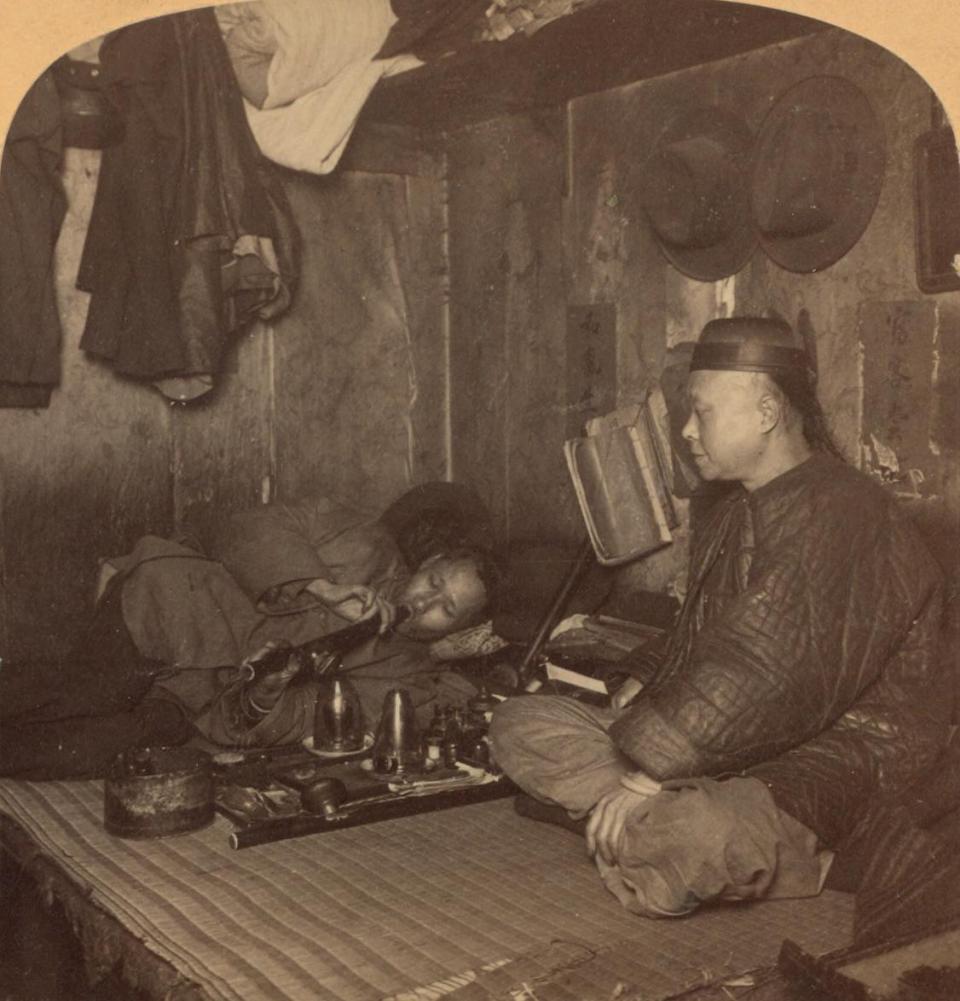

As ships arrived from Asia carrying both people and their customs, these smoking parlors quickly evolved from ethnic enclaves into cross-cultural meeting grounds that drew patrons regardless of social standing.

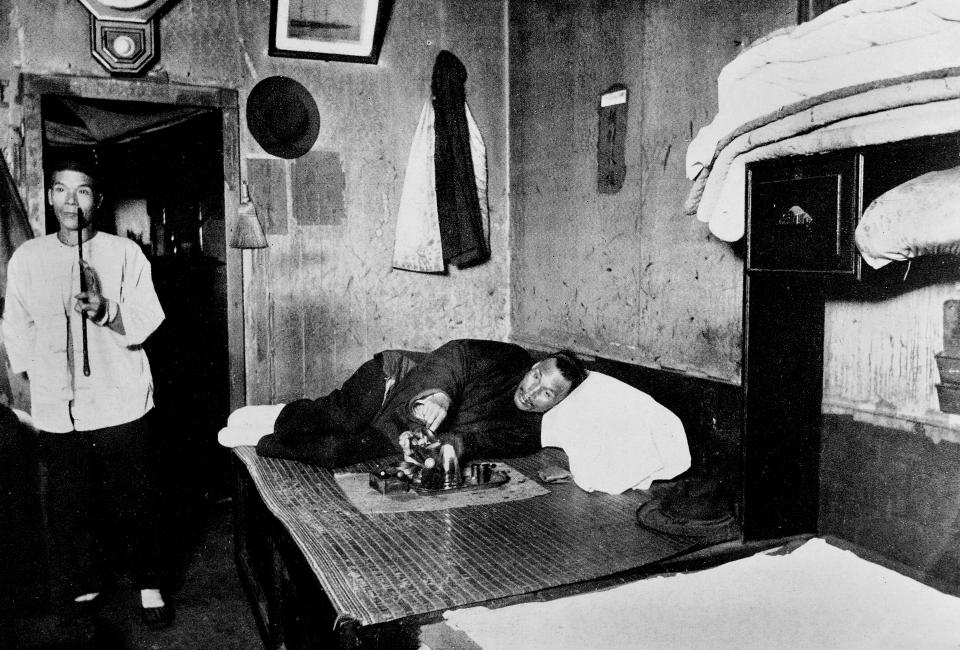

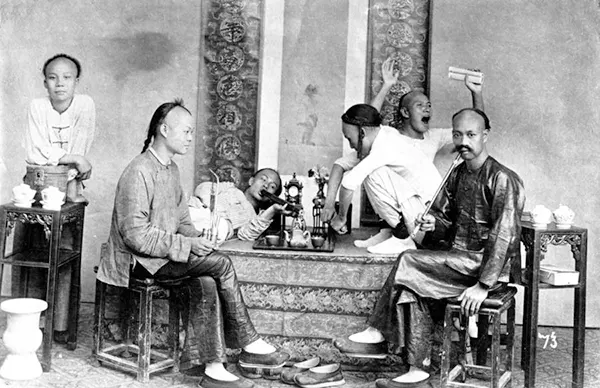

Inside these establishments, visitors would find specialized equipment essential to the smoking ritual.

Users reclined on bunk beds, positioning elongated pipes over flickering oil lamps that heated the opium until it transformed into inhalable vapor.

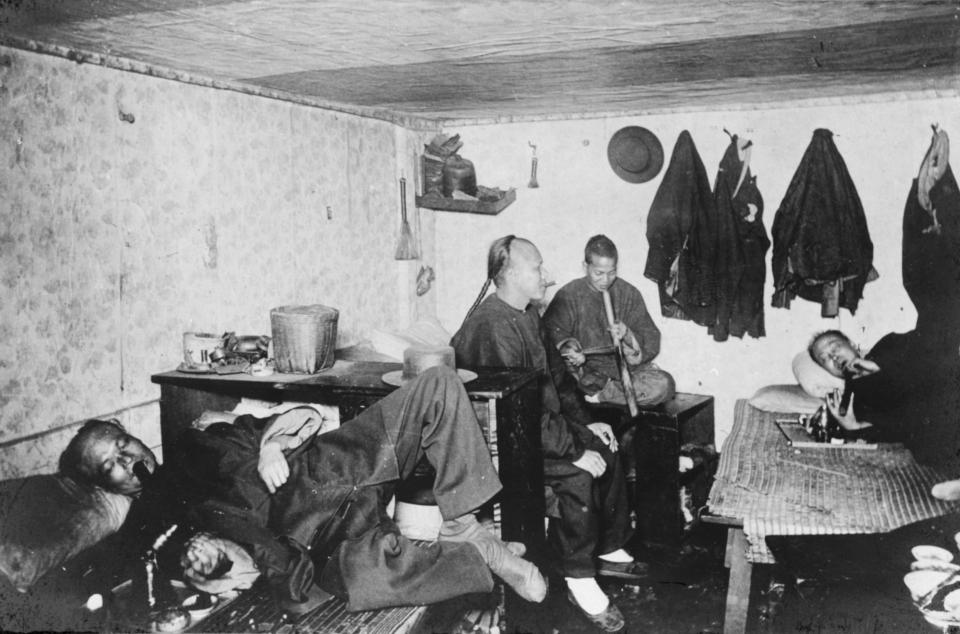

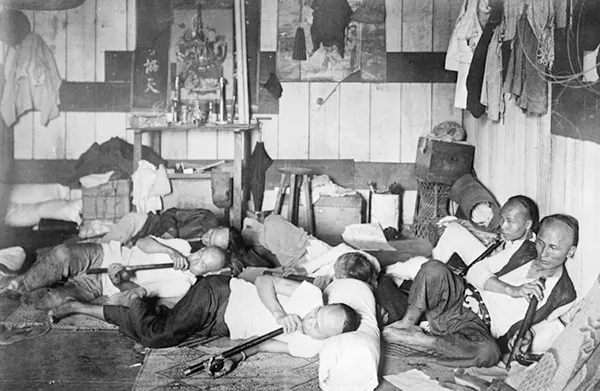

Chinese migrants smoke opium at a boarding house in San Francisco in the late 19th century.

The process required patience and specific paraphernalia, which den operators kept readily available for their clientele.

The phenomenon reached its zenith during the 1880s and 1890s, a period that paradoxically coincided with the temperance movement’s crusade against alcohol.

San Francisco became ground zero for this cultural collision, as the city served as the primary gateway to California’s gold fields.

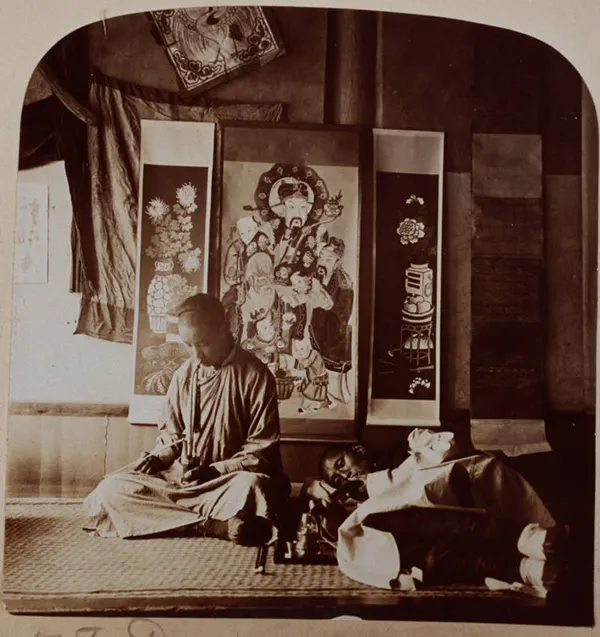

An opium den in San Francisco circa 1890, one of many such establishments that opened in the city’s Chinatown.

Chinese immigrants arriving around 1850 established Chinatown as the epicenter of opium culture, with many turning to the drug as psychological refuge from the isolation and discrimination they faced in their adopted homeland.

Municipal authorities responded in 1863 with anti-vice regulations that outlawed both opium rooms and prostitution, though enforcement proved inconsistent.

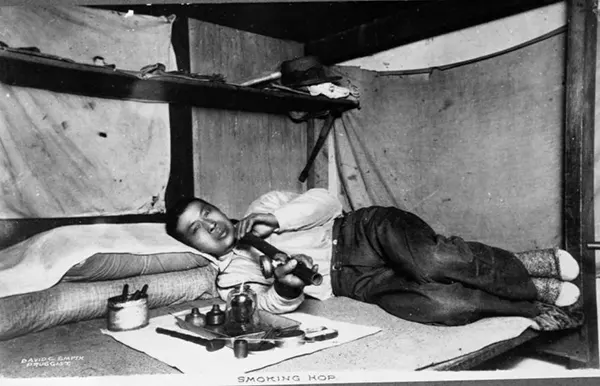

A rare photo showing a close-up of a user preparing a ‘pill’ of opium for the pipe.

By the 1870s, curiosity and addiction had drawn significant numbers of non-Chinese residents into Chinatown’s smoking parlors.

This demographic shift alarmed civic leaders enough to prompt the nation’s first anti-drug legislation: an 1875 city ordinance specifically targeting opium dens.

The typical San Francisco establishment often operated covertly within legitimate businesses—a Chinese laundry might conceal a smoking room in its basement or upper floor, carefully sealed against drafts that could disturb the lamps or allow telltale fumes to drift into the streets.

An adolescent smokes opium in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1880s, one of thousands of addicts in the USA at the time.

Literary accounts sometimes embellished these spaces as labyrinthine networks sprawling beneath ordinary storefronts.

When an undercover reporter for San Francisco’s The Examiner investigated a local opium den for herself in 1882, she was taken aback by how casual and pervasive the drug had become. She was even more appalled by the sophisticated backgrounds of the drug users she came across.

“Two white girls, neither of whom were over 17 years of age, dressed in clothes usually reserved for a Sunday picnic,” she wrote. The experience made her realize just how commonplace the new drug had become.

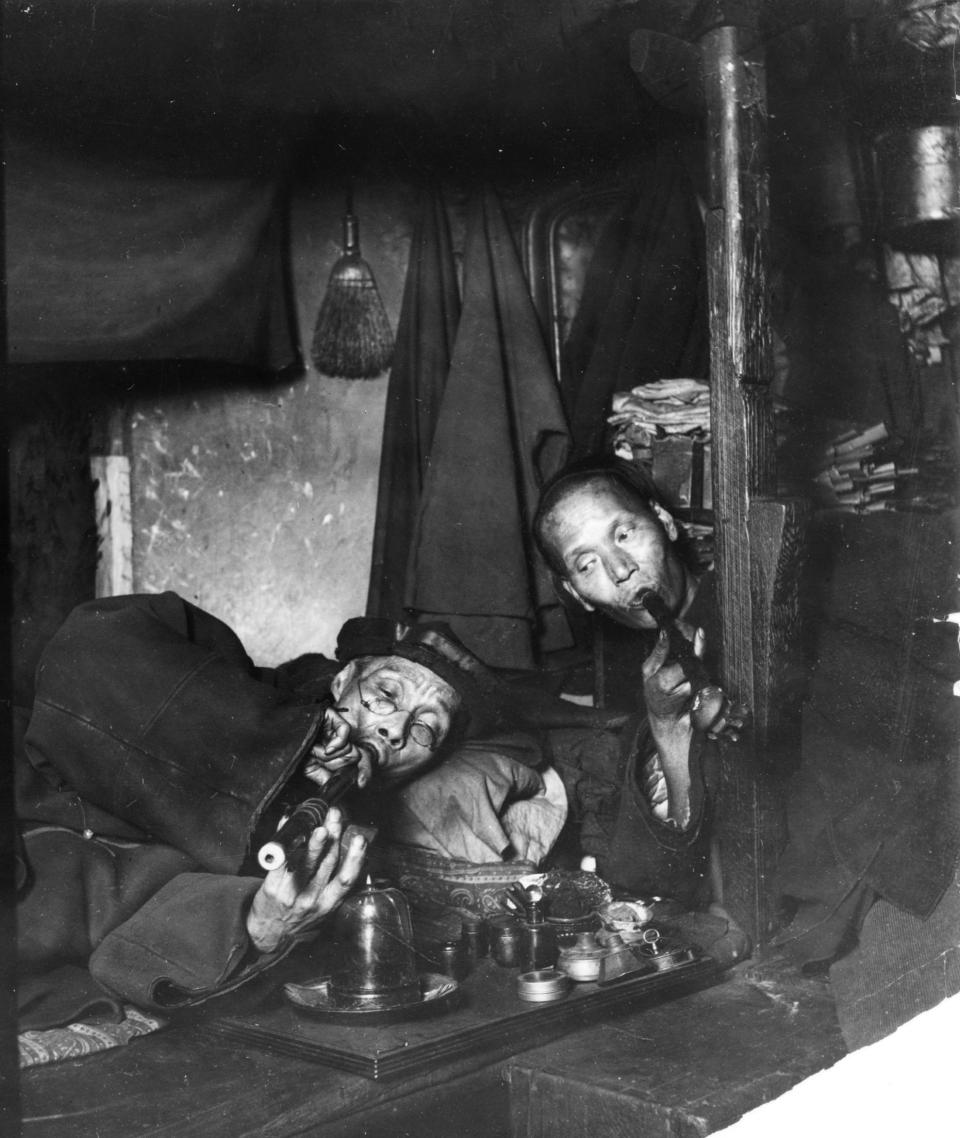

Opium smoking was brought to America by the rush of migrants during the California Gold Rush. These two men were pictured in San Francisco in 1898.

While photographer I.W. Taber documented one luxurious San Francisco den in 1886, this captured glimpse represented an exception rather than the norm.

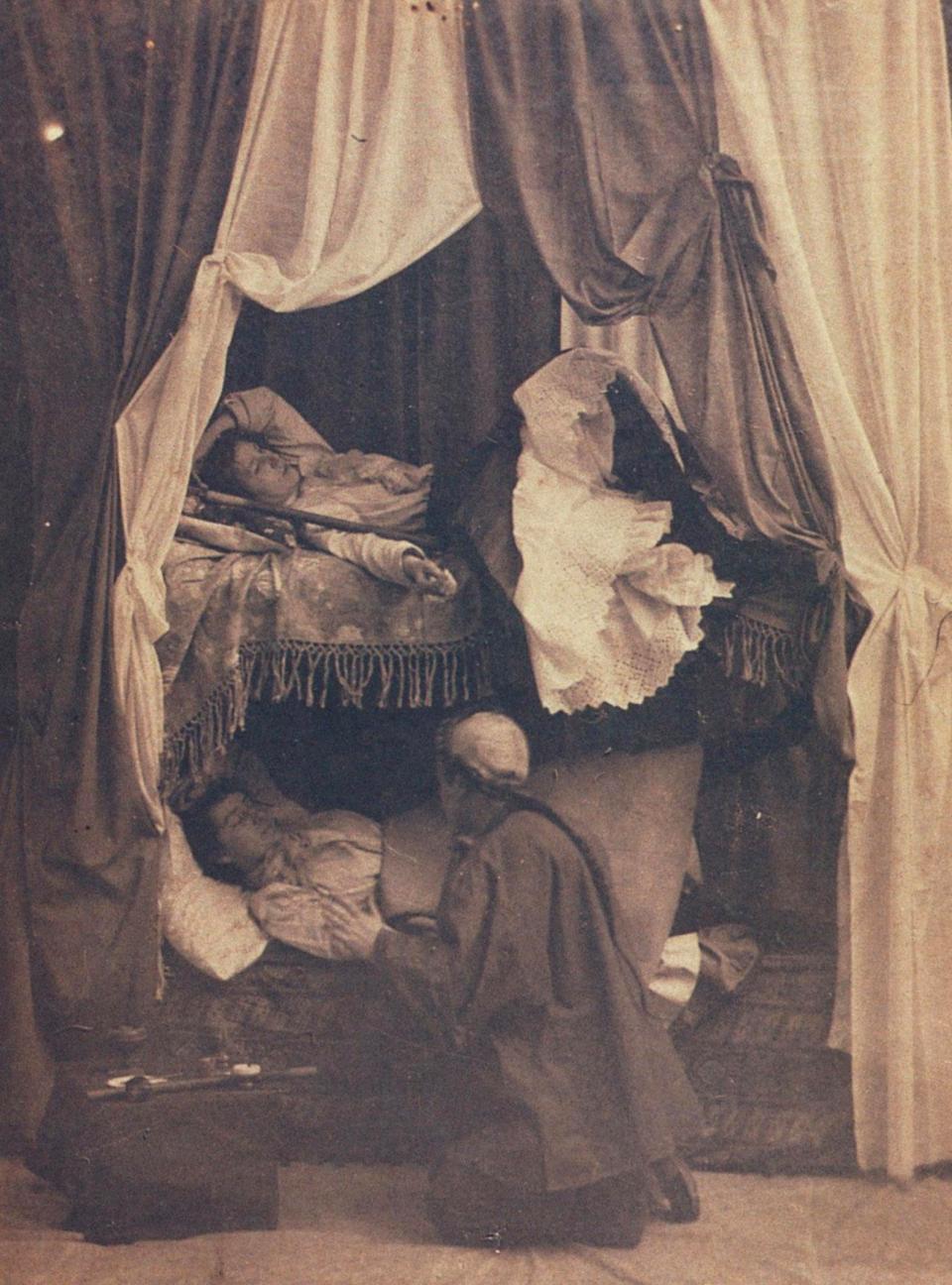

Wealthy opium users, both Chinese and white, typically avoided public venues entirely, preferring the discretion of private consumption in their own residences.

As establishments began infiltrating respectable neighborhoods, however, communal smoking gained momentum, and participation among middle and upper-class white Americans surged.

Two women are tended to as they lie in beds in one of the more upmarket dens in New York in around 1899.

The opium landscape in New York City’s Chinatown presented a starker contrast to West Coast luxury.

Dr. H.H. Kane, who conducted extensive research into opium use throughout the 1870s and 1880s, identified Mott and Pell Streets as home to the city’s most frequented joints.

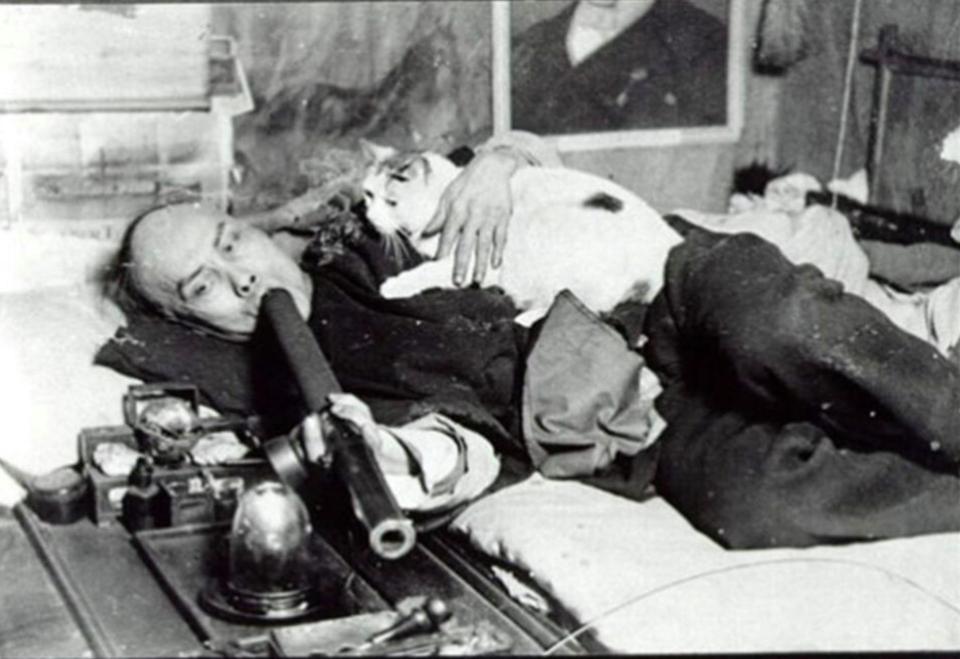

A Chinese immigrant puffs on a pipe while holding a cat in a 1900 image that became a best-selling tourist postcard in San Francisco.

Chinese proprietors operated nearly all of these establishments, with one notable exception on 23rd Street run by an American woman and her daughters.

Kane observed these dens as rare democratic spaces where “all nationalities seem indiscriminately mixed,” creating an unlikely social melting pot beneath the city’s surface.

A pair of Chinese men pose for the camera while smoking opium in New York in 1909.

The growing epidemic eventually forced governmental intervention through a succession of legislative actions.

Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, followed by the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act in 1909, marking the federal government’s first concerted efforts to combat what had become a nationwide addiction crisis threatening American society across all boundaries of class and ethnicity.

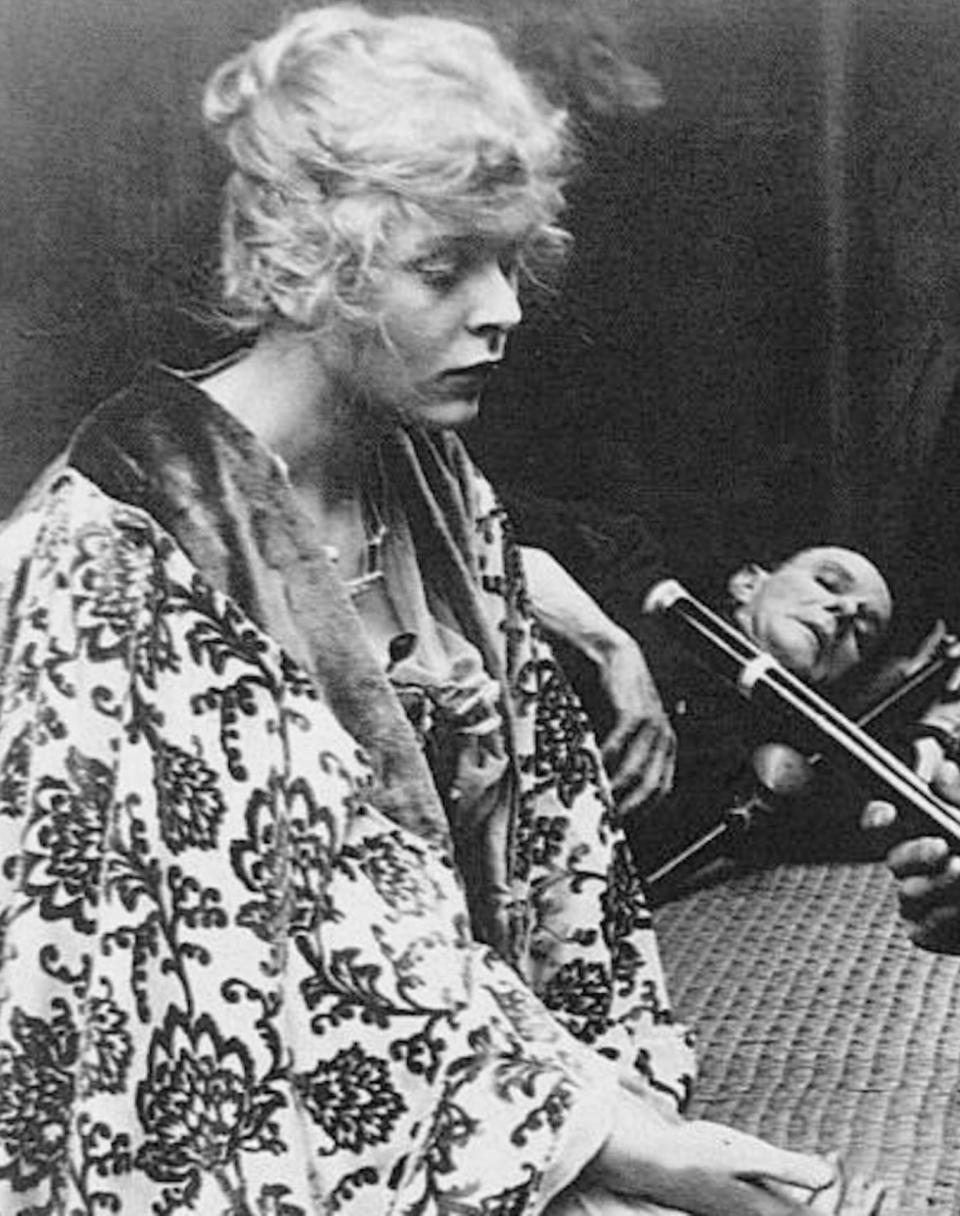

A forlorn-looking white woman stares at an opium pipe in New York in around 1910.

In the end, changing public attitudes did more to diminish opium’s presence than any single law ever could.

As the nation approached the Second World War, the once-notorious opium dens were already fading, and regular use of the drug had declined significantly across the country.

A Chinese-American man hangs an elaborate scroll with Chinese characters on a wall in a den in Hop Alley in Denver, Colorado, in around 1912.

A lone den at 295 Broome Street in Manhattan continued operating until 1957, but it was an outlier in a scene that had largely disappeared.

By the mid-20th century, Americans—and much of the Western world—had turned away from what had long been portrayed as an exotic Eastern indulgence.

Instead, everyday social life centered on bars, taverns, and cigarette smoke, reflecting a broader shift in habits and cultural identity.

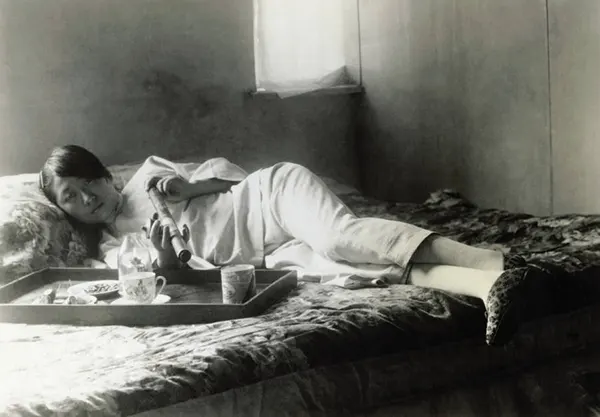

The craze swept the nation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, This woman smokes opium in her own home in San Francisco circa 1920.

Western men and women of upper and middle class means began to frequent dens like this one in New York in 1923.

Smartly dressed opium smokers lounge around in an opium den in New York in 1925 as the drug craze swept the country.

Four well-to-do white women lie around a Chinese man, all clearly intoxicated, in New York in 1926.

One of the many opium dens of New York in the 1920s. Chinatown, New York. April 12, 1926.

Opium dens were sure to provide their customers with the right equipment, including pipes, hookahs, vases, and the like. 1800s.

Opium dens could be opulent and luxurious spaces to cater to their affluent clientele. Others were cluttered and low-end, like this one. 1892.

Two women entranced in an opium den. New York, 1902.

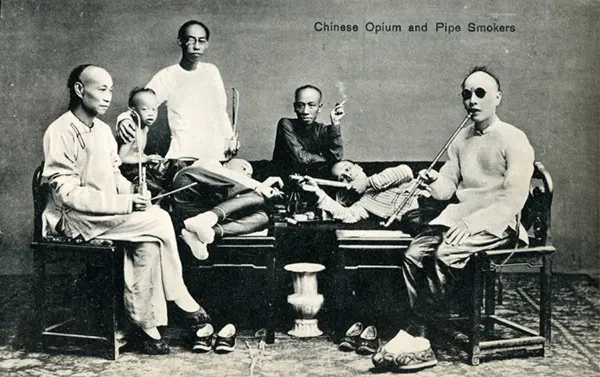

Opium smokers in China in the early 20th century.

Opium comes from the sap of a specific “opium” poppy. China, 1900s.

Chinese people smoking the “evil poppy” in an opium den.

Dr. Hamilton Wright, the Opium Commissioner of the United States, told The New York Times in 1911 that “Opium, the most pernicious drug known to humanity, is surrounded, in this country, with far fewer safeguards than any other nation in Europe fences it with.” This photo is dated 1874.

An opium den in the Chinese district in Paris, France. 1930.

Opium Den in Hong Kong, China, 1920.

“It is a wretched hole…so low that we are unable to stand upright,” reported a French journal of an English opium den in 1868.

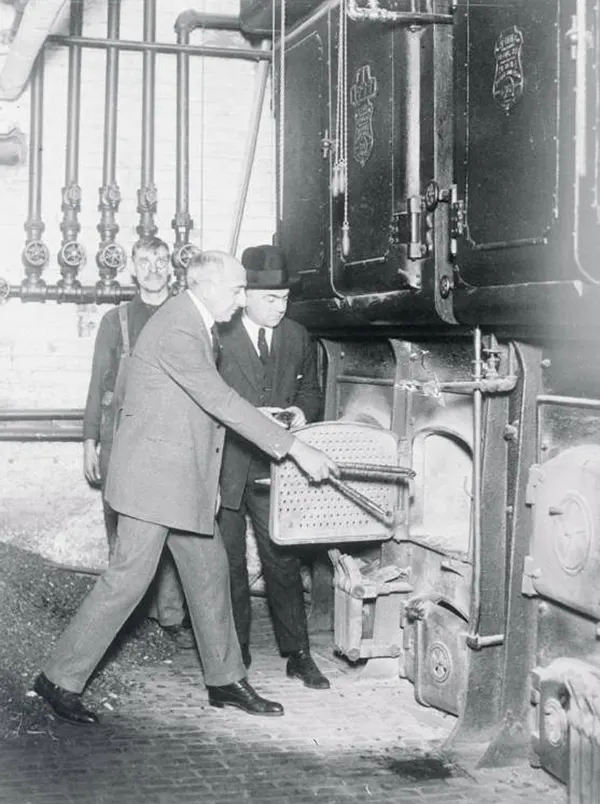

Deputy Commissioner Dr. Carleton Simon in the midst of destroying opium pipes. New York. Feb. 10, 1922.

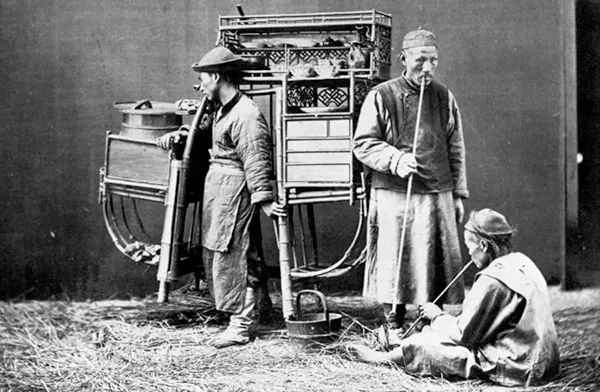

An opium dealer with his cart and some customers. China, 1900s.

A conference on the influx of opium and prevalence of dens in the U.S. (1900s).

Middle Eastern opium sellers weighing the drug in an open market place. Persia, 1900s.

Opium pipes worth several thousand dollars are burned at a public dumping ground.

Opium smokers in China, 1880.

A group of opium smokers joke and pose in their den. Shanghai, China. 1898.

A postcard featuring a group of opium smokers. Shanghai, China, 1910.

Smokers in China, 1867.

American women protesting the opium trade outside a government building, 1920.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Daily News / Pinterest / Flickr).