Standing tall for centuries in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan, the colossal Buddha statues were awe-inspiring monuments to the region’s rich Buddhist heritage and its role as a crossroads of ancient civilizations.

Carved directly into the cliffs during the 6th century, these towering figures once symbolized harmony and cultural exchange along the Silk Road.

Their serene presence echoed a time when art, religion, and trade flourished in the heart of Central Asia.

Tragically, this legacy was violently erased in 2001, when the Taliban carried out their destruction, reducing these masterpieces to rubble and leaving behind a cultural void.

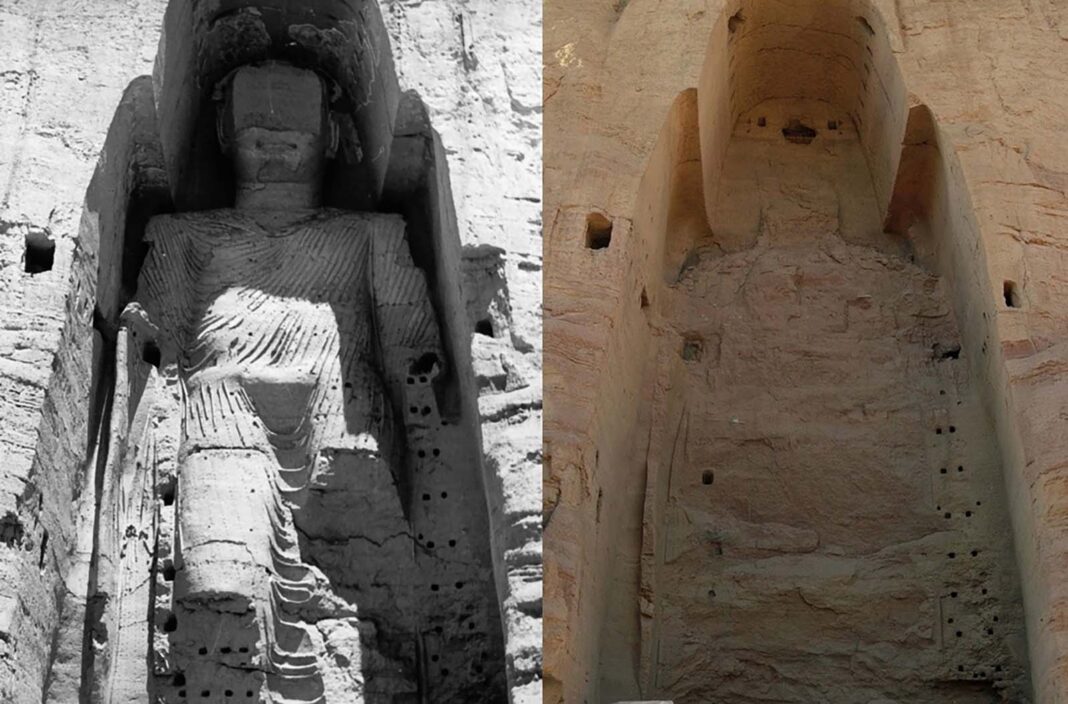

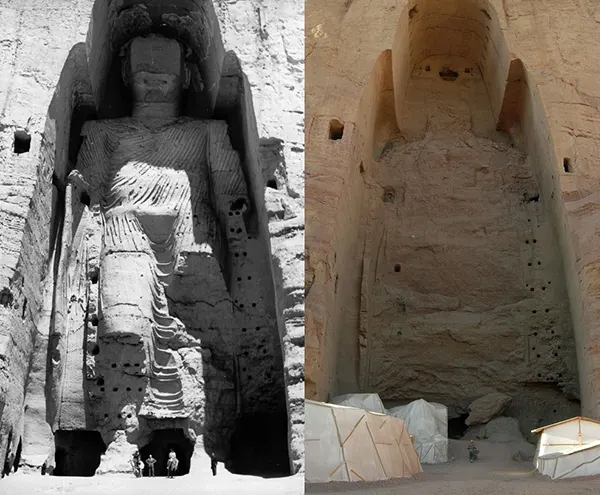

Smaller, 38 meter Buddha, before and after destruction. The paintings of Hepthalite royal sponsors on the ceiling have also disappeared.

Nestled 130 kilometers (81 miles) northwest of Kabul at an altitude of 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), the Bamiyan Buddhas were monumental carvings that stood as silent witnesses to Afghanistan’s rich Buddhist heritage.

Carbon dating reveals that the smaller “Eastern Buddha,” measuring 38 meters (125 feet), was constructed around 570 CE, while the larger “Western Buddha,” at 55 meters (180 feet), was completed around 618 CE.

These dates place their creation during the Hephthalite rule, a period when Buddhism flourished in the region.

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the statues served as a sacred site for pilgrims traveling the Silk Road, connecting cultures and spiritual practices across continents.

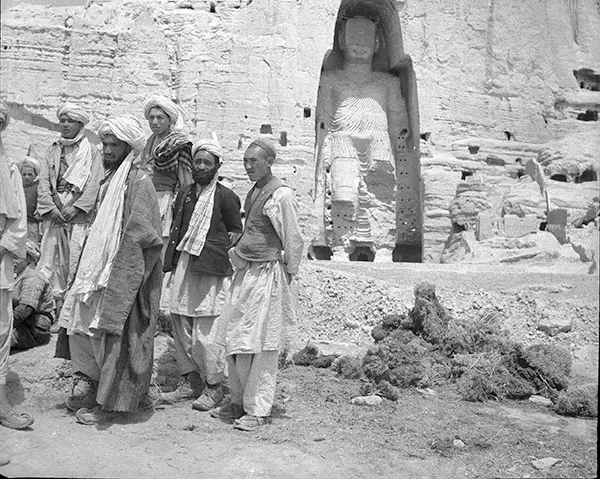

Smaller, 38 meter Buddha in 1977.

The Buddhas embodied a sophisticated blend of Greco-Buddhist art that evolved from the Gandhara tradition.

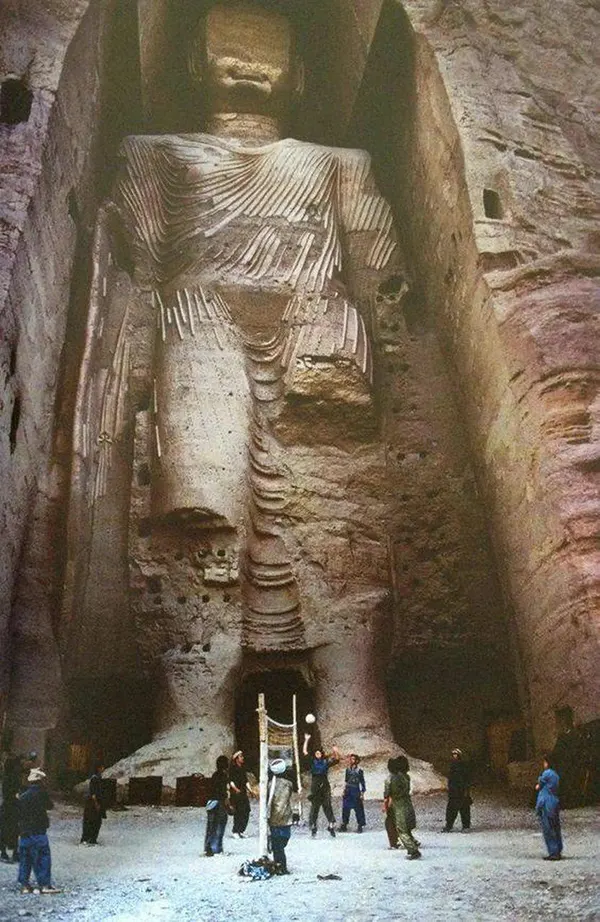

The larger figure, called “Salsal,” meaning “the light shines through the universe,” was regarded as male, while the smaller, known as “Shah Mama,” or “Queen Mother,” was seen as female.

Both statues were reliefs, merging seamlessly into the sandstone cliffs from which they were carved.

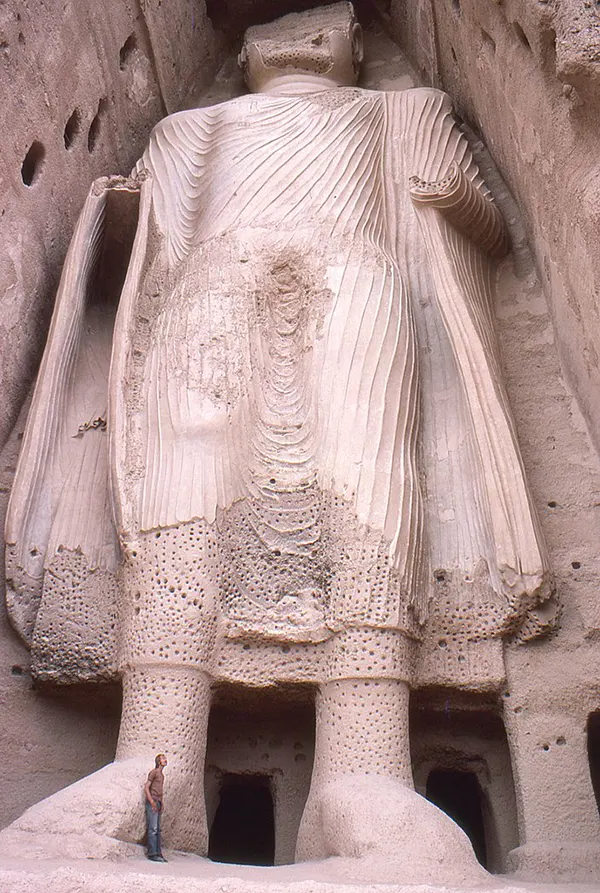

Larger 55-metre (180 ft) “Western Buddha”.

The figures’ bodies were sculpted directly from the cliffs, with details like faces, hands, and robes modeled in a mixture of mud and straw, coated with stucco, and painted for added depth and expression.

Salsal was adorned with a carmine red hue, while Shah Mama was painted in vibrant multicolored tones.

Their arms and facial features, crafted separately using wooden frameworks and masks, added intricate dimensionality to the sculptures.

Local men standing near the larger “Salsal” Buddha statue, c. 1940.

Bamiyan had been a center of Buddhist devotion since the 2nd century CE under the Kushan Empire, thriving along the Silk Road.

This continued until the region fell under Islamic rule after the conquests of 770 CE, culminating in Turkic Ghaznavid control by 977 CE.

Despite political upheavals, the Buddhas endured, even surviving the devastation wrought by Genghis Khan in 1221, which obliterated much of the valley’s population.

Smaller, 38 meter Buddha in 1977.

In the 17th century, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb attempted to destroy the statues with artillery, inflicting some damage, though the Buddhas largely remained intact.

Surrounding the statues were intricate caves and walls adorned with vivid paintings, most of which date to the 6th to 8th centuries CE and had come to an end with the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan.

Possible reconstitution of the original appearance of the Western Buddha (Vairocana).

In August 1998, the Bamiyan Valley found itself entirely encircled by the Taliban. Among the militants was a local commander who had long declared his intent to destroy the iconic Buddha statues.

He began by drilling holes into their heads, intending to load them with explosives. However, his plans were temporarily halted by Mohammed Omar, the Taliban’s de facto leader.

Despite this intervention, others damaged the smaller Buddha’s head using dynamite, targeted the larger Buddha’s groin with rocket fire, and set tires ablaze at its head, leaving visible scars on these ancient monuments.

On March 1, 2001, the Taliban officially announced a directive to destroy all statues depicting human forms in Afghanistan, declaring them un-Islamic.

On March 1, 2001, the Taliban officially announced a directive to destroy all statues depicting human forms in Afghanistan, declaring them un-Islamic.

The systematic destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas began the next day and continued for several weeks in a grim sequence of calculated assaults.

The process unfolded in stages. Initially, the statues were bombarded with anti-aircraft guns and artillery fire over several days, causing significant damage but failing to fully destroy them.

Mural of the Sun God riding his golden chariot and rows of royal donors along the sides, over the head of the smaller 38 meter Eastern Buddha (carbon-dated to 544–595 CE).

Taliban Information Minister Qudratullah Jamal acknowledged the complexity of the task, stating, “The destruction work is not as easy as people would think.

You can’t knock down the statues by dynamite or shelling, as both of them have been carved in a cliff. They are firmly attached to the mountain.”

Site of the larger statue after it was destroyed.

To overcome these challenges, the Taliban escalated their efforts, placing anti-tank mines at the base of the niches. These mines were triggered by falling rock fragments from artillery fire, amplifying the destruction.

Finally, men were lowered down the cliff face to insert explosives directly into holes drilled into the statues. Even then, complete obliteration proved elusive.

When one explosion failed to destroy the face of one of the Buddhas, a rocket was fired, leaving a gaping hole in the remnants of its stone visage.

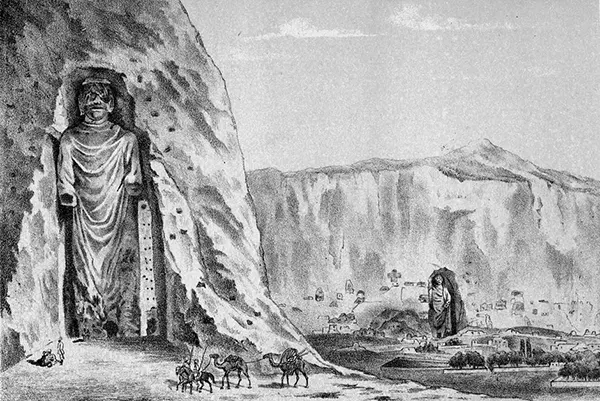

Engraving of the Buddhas, 19th century.

Various theories have sought to explain what prompted Taliban leader Mullah Omar to order the destruction of the statues, further complicated by seemingly shifting narratives of the events as relayed by Omar and senior Taliban officials.

On 6 March 2001, British newspaper The Times quoted Omar as stating “Muslims should be proud of smashing idols. It has given praise to Allah that we have destroyed them.”

Taller Buddha, after destruction.

In 2004, following the American invasion of Afghanistan and his exile, Omar explained in an interview: I did not want to destroy the Bamiyan Buddha.

In fact, some foreigners came to me and said they would like to conduct the repair work of the Bamiyan Buddha that had been slightly damaged due to rains. This shocked me.

I thought, these callous people have no regard for thousands of living human beings—the Afghans who are dying of hunger, but they are so concerned about non-living objects like the Buddha.

This was extremely deplorable. That is why I ordered its destruction. Had they come for humanitarian work, I would have never ordered the Buddha’s destruction.

Smaller Buddha, after destruction.

The destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas despite protests from the international community has been described by Michael Falser, a heritage expert at the Center for Transcultural Studies in Germany, as an attack by the Taliban against the globalizing concept of “cultural heritage”.

The UNESCO Director-General Kōichirō Matsuura called the destruction a “…crime against culture. It is abominable to witness the cold and calculated destruction of cultural properties which were the heritage of the Afghan people, and, indeed, of the whole of humanity.”

View of the rock where monasteries and Buddhas are carved.

Destruction of the site by the Taliban.

Smaller 38-metre (125 ft) “Eastern Buddha”.

Taller, 55 meter Buddha in 1963 and in 2008 after destruction.

Panorama of the northern cliff of the Valley of Bamyan, with the Western and Eastern Buddhas at each end (before destruction), surrounded by a multitude of Buddhist caves.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Upscaled and enhanced by RHP).