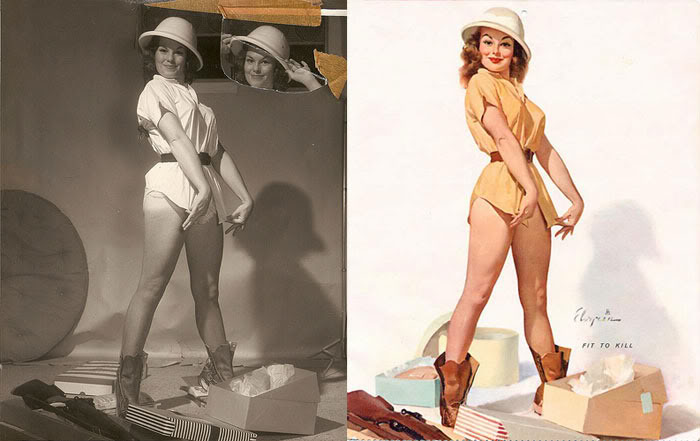

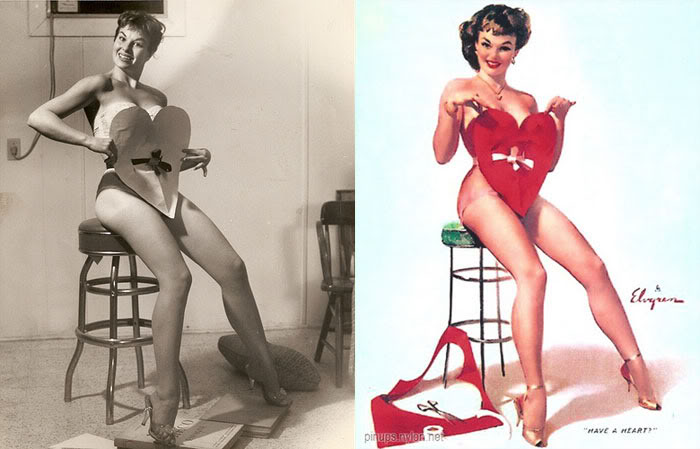

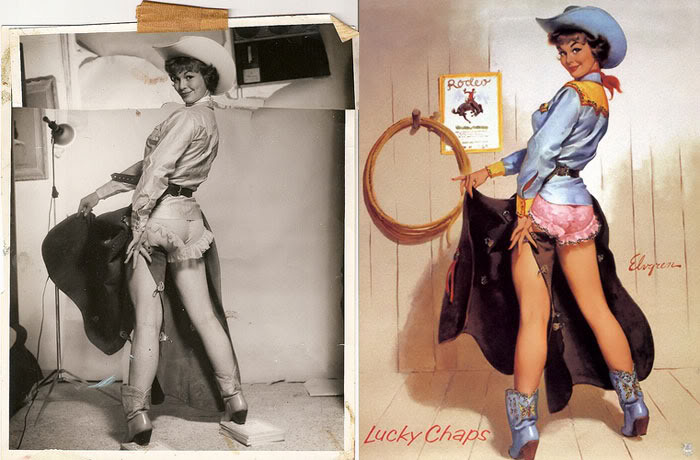

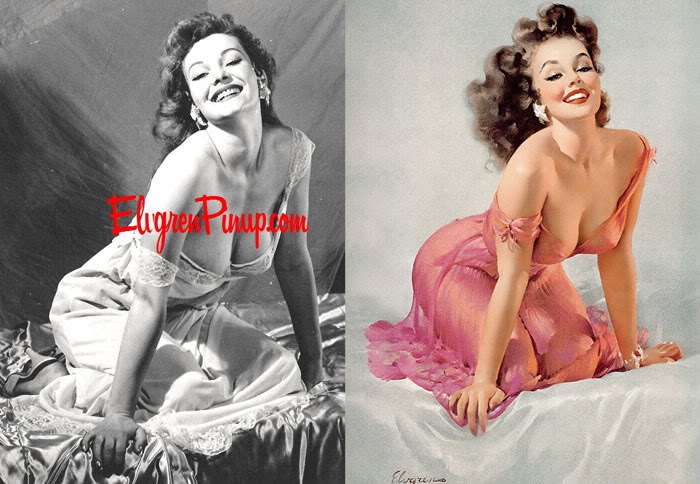

Long before Photoshop and digital touch-ups, the art of seduction was perfected with paint.

In the 1940s and 1950s, pin-up girls became cultural icons, their images gracing bomber planes, barracks walls, and magazine pages.

They weren’t just pictures; they were carefully crafted fantasies that boosted morale and embodied an idealized version of beauty.

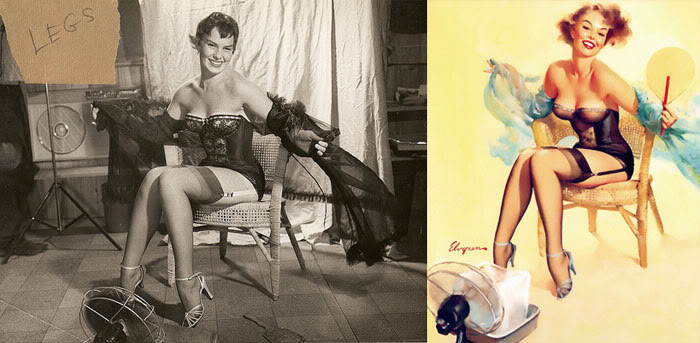

At the center of this golden era stood Gil Elvgren, an artist whose playful, exaggerated depictions of women turned everyday scenes into irresistible works of art.

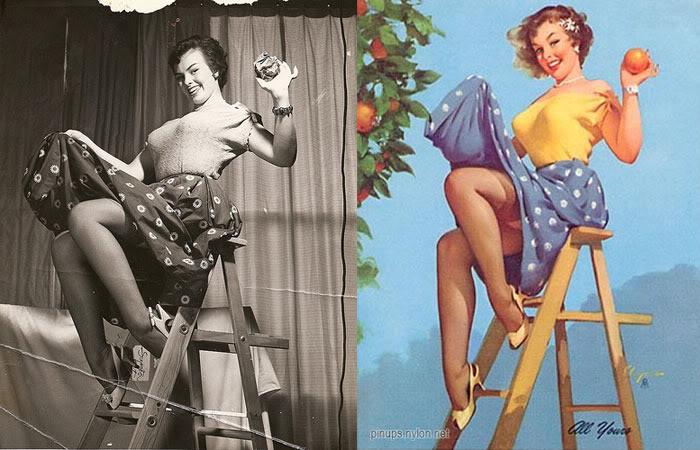

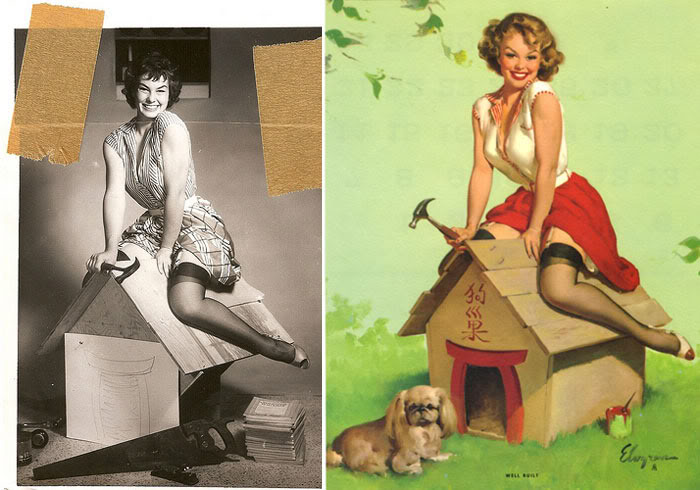

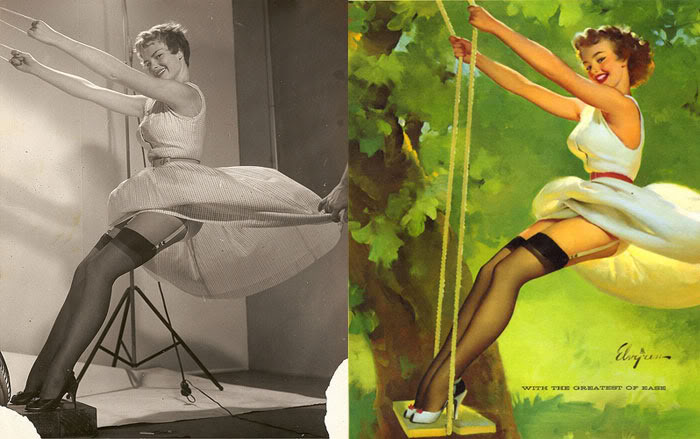

Elvgren’s paintings often portrayed women in lighthearted, sometimes mischievous situations—lifting a skirt on a windy day, caught in a moment of surprise, or striking a pose that blurred the line between innocence and allure.

Elvgren’s paintings often portrayed women in lighthearted, sometimes mischievous situations—lifting a skirt on a windy day, caught in a moment of surprise, or striking a pose that blurred the line between innocence and allure.

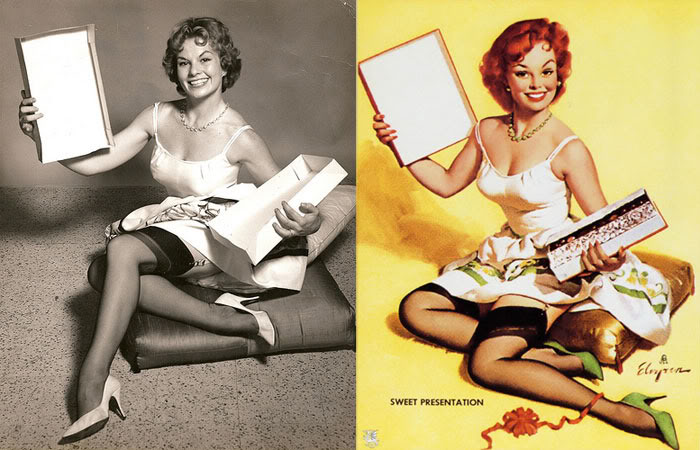

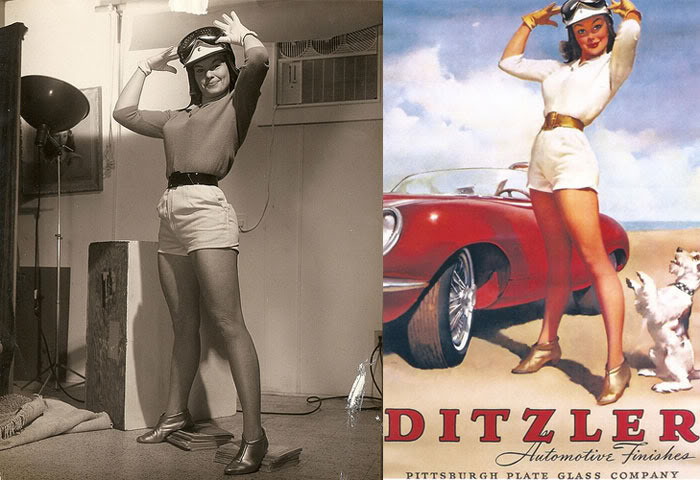

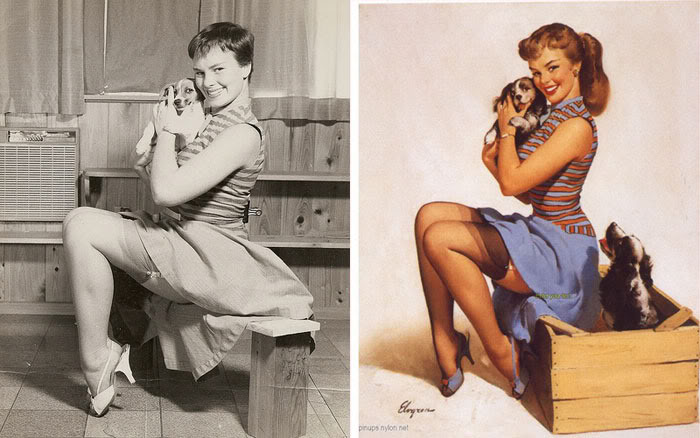

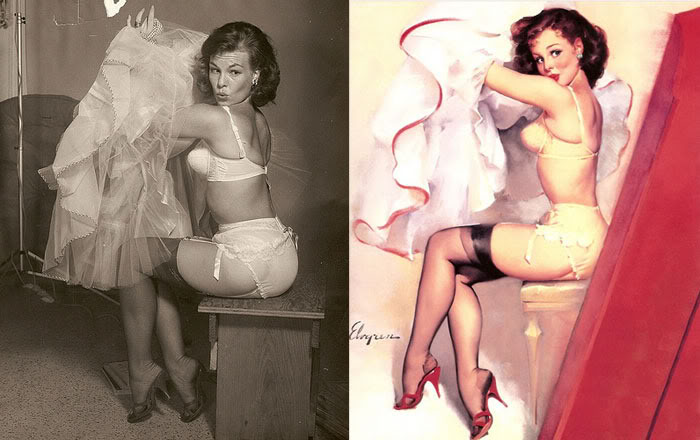

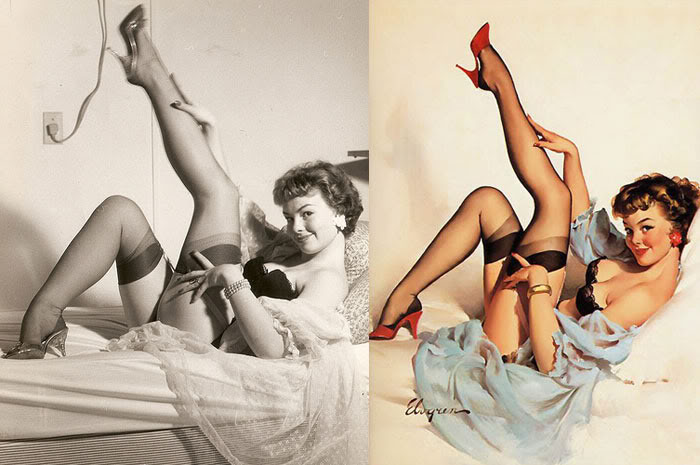

The women were based on real models, but once Elvgren’s brush touched the canvas, they became something more.

Legs grew longer, waists slimmer, expressions brighter, and every detail leaned toward an unattainable perfection.

These before-and-after transformations reveal how much artistry, not photography, shaped the era’s most iconic visions of femininity.

The phenomenon of the pin-up had deep roots in American culture. A pin-up model was typically a glamorous actress, dancer, or fashion model whose photographs or paintings were mass-produced for casual display, often tacked to lockers or bedroom walls.

The phenomenon of the pin-up had deep roots in American culture. A pin-up model was typically a glamorous actress, dancer, or fashion model whose photographs or paintings were mass-produced for casual display, often tacked to lockers or bedroom walls.

By the 1940s, the term “cheesecake” became a popular American slang for these alluring yet playful images.

Their appeal lay in their accessibility—they suggested desire without descending fully into the risqué, offering fantasy with just enough modesty to feel acceptable for the times.

The word “pin-up” itself entered the English language in 1941, and from then on, these images appeared everywhere: magazines, newspapers, postcards, calendars, and lithographs.

The word “pin-up” itself entered the English language in 1941, and from then on, these images appeared everywhere: magazines, newspapers, postcards, calendars, and lithographs.

They quickly became a cultural language of glamour and longing, shaping how beauty and femininity were imagined in the mid-20th century.

Hollywood celebrities also played a key role in popularizing the pin-up. Film stars who captured the public’s imagination were not only photographed but often transformed into posters or paintings for personal keepsakes.

Hollywood celebrities also played a key role in popularizing the pin-up. Film stars who captured the public’s imagination were not only photographed but often transformed into posters or paintings for personal keepsakes.

One of the most famous examples was Betty Grable, whose iconic swimsuit poster became a fixture in G.I. lockers during World War II.

She wasn’t just a screen siren; she became a symbol of hope and charm carried across oceans to soldiers far from home.

Pin-ups weren’t limited to photographs or film stills—art gave illustrators the freedom to exaggerate, to create women who reflected not only beauty but cultural ideals.

Pin-ups weren’t limited to photographs or film stills—art gave illustrators the freedom to exaggerate, to create women who reflected not only beauty but cultural ideals.

A notable early example was the “Gibson Girl,” created by Charles Dana Gibson in the late 19th century.

She represented the “New Woman”—independent, fashionable, and symbolic of changing attitudes toward gender and sexuality.

Unlike earlier photographed figures, artistic renderings allowed for endless reinvention, letting the image of womanhood evolve alongside society itself.

By the 1930s and 1940s, magazines such as Esquire helped cement the popularity of pin-up art. Among its most famous creations were the “Vargas Girls,” drawn by Alberto Vargas. Initially admired for their elegance and beauty,

By the 1930s and 1940s, magazines such as Esquire helped cement the popularity of pin-up art. Among its most famous creations were the “Vargas Girls,” drawn by Alberto Vargas. Initially admired for their elegance and beauty,

Vargas’s pin-ups became more provocative during World War II, often depicted in playful military attire and flirtatious poses.

Their popularity was immense—between 1942 and 1946, over nine million copies of Esquire, stripped of advertising and distributed free of charge, were sent to American troops overseas.

Their popularity was immense—between 1942 and 1946, over nine million copies of Esquire, stripped of advertising and distributed free of charge, were sent to American troops overseas.

For many soldiers, these images became a cherished connection to home, blending nostalgia with fantasy.

Gillette Alexander Elvgren (March 15, 1914 – February 29, 1980) was an American painter known for his work in pin-up art, advertising, and illustration.

Gillette Alexander Elvgren (March 15, 1914 – February 29, 1980) was an American painter known for his work in pin-up art, advertising, and illustration.

He gained widespread recognition for his pin-up paintings created for Brown & Bigelow.

Elvgren studied at the American Academy of Art in Chicago and drew inspiration from earlier “pretty girl” illustrators such as Charles Dana Gibson, Andrew Loomis, and Howard Chandler Christy. He was also influenced by the Brandywine School of illustration, founded by Howard Pyle.

(Photo credit: Gil Elvgren / Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Pinterest).