In the summer of 1978, a routine helicopter flight over the dense forests of southern Siberia turned into one of the most extraordinary discoveries in modern Russian history.

A pilot, tasked with scouting landing zones for a group of geologists near the Mongolian border, was surveying the unforgiving terrain when something unexpected caught his eye near the basin of the Abakan River—a small, hand-built structure nestled between the trees.

It was a startling sight. The area was more than 150 miles from the nearest settlement, deep within a remote stretch of wilderness considered uninhabited.

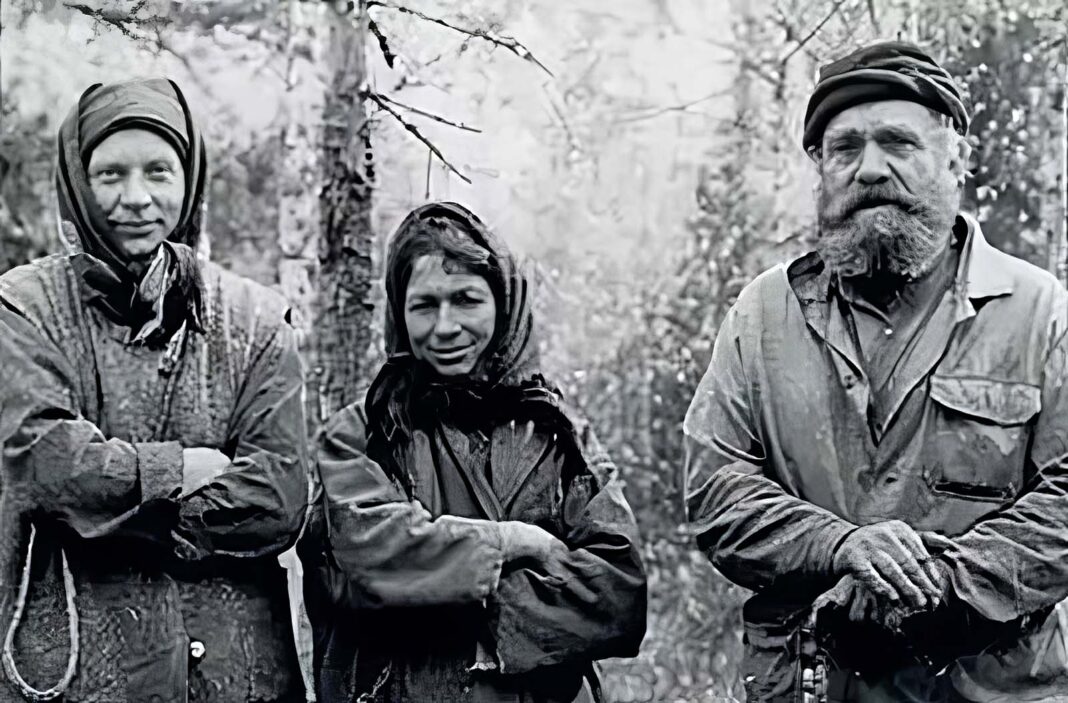

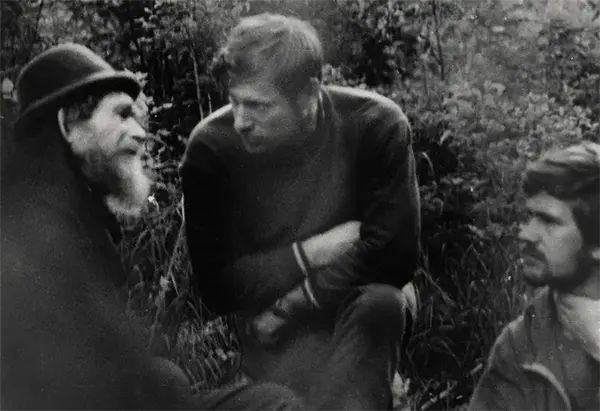

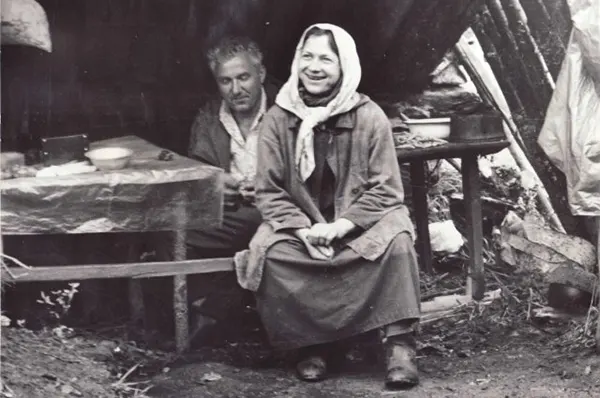

Agafia and Karp, with a journalist.

The land itself was wild and unwelcoming, a patchwork of thick forests, steep ridges, and icy streams. Yet, there it was—a lone hut standing against the odds.

Intrigued, the geologists convinced the pilot to set down nearby. Once on the ground, they hiked for hours through dense taiga and up a steep mountain slope, half-expecting the hut to vanish as a trick of the light.

But the structure was real, and signs of life surrounded it: a modest garden with sparse crops and the faint sound of voices from within.

A Russian press photo of Karp Lykov (second left) with Dmitry and Agafia, accompanied by a Soviet geologist.

The hut was crudely constructed from logs, earth, and whatever materials could be scavenged from the forest. Inside, the air was heavy with the scent of decay and damp wood smoke.

A small fire burned in one corner, casting flickering shadows across the soot-darkened walls. The floor was littered with potato peels and pine-nut shells—remnants of hard living far removed from the conveniences of Soviet life.

As the geologists took in the scene, five figures emerged from the shadows. An elderly man with a long grey beard stepped forward and calmly said, “Well, since you have travelled this far, you might as well come in.” His name was Karp Lykov.

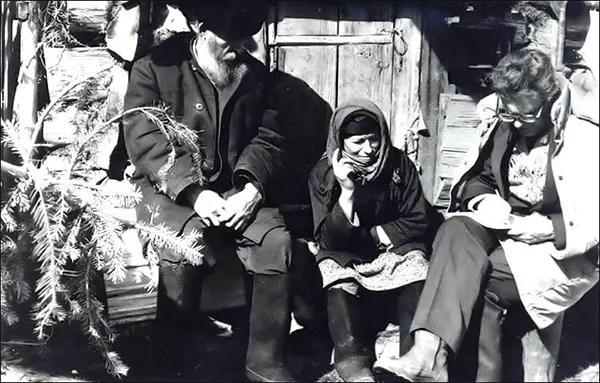

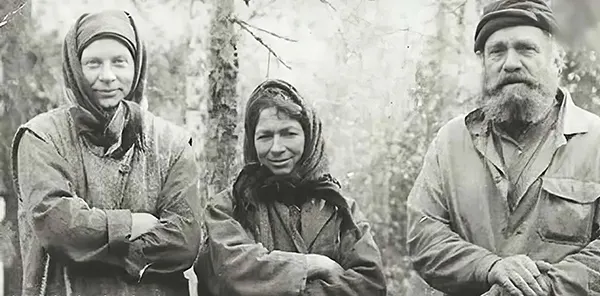

Agafia (center) and her father, Karp, 1982.

Karp introduced his four children: Savin, Natalia, Dmitriy, and Agafia. They were thin, dressed in rags, and wary of the visitors.

In the background, a woman’s voice trembled with prayer, whispering that the strangers’ arrival was punishment for their sins. The scene was surreal—like stepping into another century.

While Karp seemed willing to talk, his children kept their distance. The women, especially, appeared frightened and distraught.

The geologists, unsure how their presence might affect the family, approached the situation with care, making short, respectful visits over the next several days.

The geologists, unsure how their presence might affect the family, approached the situation with care, making short, respectful visits over the next several days.

Gradually, trust began to form. During one of these encounters, Karp began to explain how his family had ended up living in isolation, completely cut off from the outside world.

It was a story shaped by faith, fear, and survival—one that had begun decades earlier in a very different Russia.

Why the Lykovs Chose a Life of Complete Isolation

The story of how the Lykov family vanished into the Siberian wilderness begins long before that summer day in 1978.

Their disappearance was not an accident, but a deliberate act of escape—rooted in faith, fear, and a desperate need for freedom.

The Lykovs were part of a devout religious sect known as the Old Believers, an offshoot of Russian Orthodoxy that had resisted liturgical reforms dating back to the 17th century.

Since the reign of Peter the Great, they had endured waves of persecution, viewed as heretics by the Russian state and official church alike.

For centuries, many Old Believers had sought refuge in remote areas to preserve their traditional ways, far from the prying eyes of authorities.

For centuries, many Old Believers had sought refuge in remote areas to preserve their traditional ways, far from the prying eyes of authorities.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the pressure intensified. The newly formed Soviet regime took an even harsher stance toward religion, and many Old Believer communities scattered to the edges of the Russian empire to avoid harassment and violence.

But the most brutal period came in the 1930s during Stalin’s Great Purge, when practicing Christianity became not only dangerous but illegal. Worship was criminalized, churches were destroyed, and believers were arrested or killed.

Agafia (center) and her father, Karp, 1982.

Karp Lykov, a young man at the time, experienced this crackdown firsthand. One day, while working in the fields, he watched in horror as a Soviet patrol shot his brother in cold blood for their religious beliefs.

That single moment changed the course of his life. With the threat closing in and no hope for safety within the borders of Soviet society, Karp made a life-altering decision—to flee.

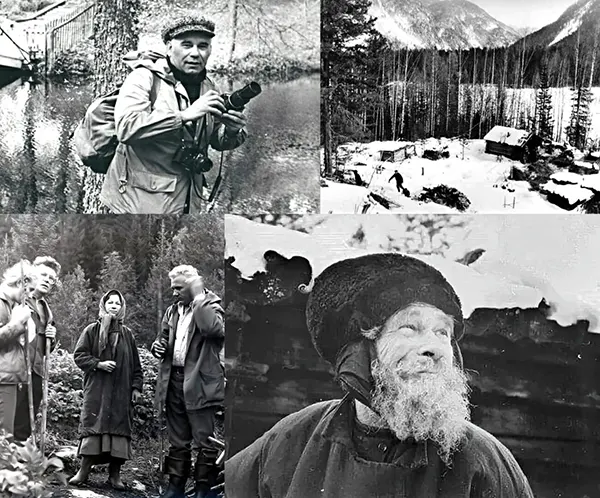

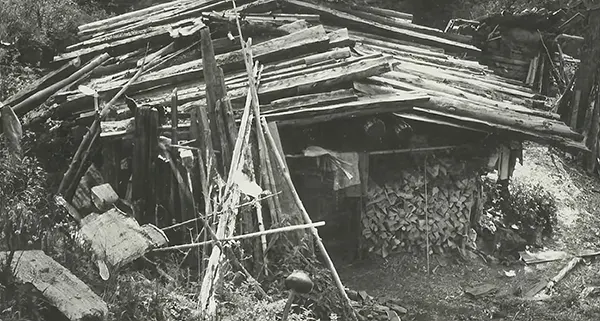

The hut where the Lykov’s lived.

In 1936, Karp gathered what little he had: his wife, Akulina, their nine-year-old son Savin, two-year-old daughter Natalia, a few household items, and a handful of seeds.

Together, they disappeared into the Siberian taiga. What began as an escape turned into a lifelong exile.

Year by year, the family pushed farther into the forest, avoiding all contact with the outside world.

The Lykovs’ homestead seen from a Soviet reconnaissance plane, 1980.

They built makeshift cabins along the way, gradually learning how to survive off the land.

Eventually, they settled in a remote and forbidding location, more than 6,000 feet above sea level on a mountainside near the Yerinat River in the Abakan River basin.

The spot was so remote that it lay 250 kilometers—about 160 miles—from the nearest human settlement.

The Lykovs’ graves.

A Life Carved Out of the Wilderness

With only a few metal pots and basic tools brought from the outside world, the Lykovs relied entirely on their surroundings for survival.

Their diet was meager—mostly potatoes, rye, berries, and the rare animal they managed to catch. Hunting was limited, and foraging became a daily necessity.

When their clothing wore out, they crafted replacements from hemp and birch bark. These materials offered minimal protection against the freezing temperatures, but it was all they had.

As the years passed, even their cooking vessels began to fail. Akulina, ever resourceful, fashioned new containers from bark and whatever else she could find, but without metal, cooking became impossible. The fire in their cabin served only to keep them from freezing.

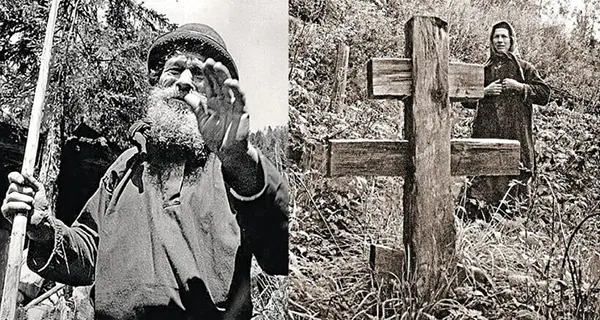

Karp, Agafia, and Natalia Lykov, 1978.

Amid the hardship, there were also moments of joy. Dmitry and Agafia were born in the wilderness, wrapped in handmade cloth and fitted with tiny bark shoes.

Karp devoted himself to teaching his children the skills they needed to survive—how to gather clean water, cut firewood, and maintain the fragile shelter that protected them from the elements.

But in 1961, disaster struck. An unseasonal snowfall in June wiped out their crops, leaving the family without food reserves.

Their staple potatoes had frozen in the ground, and with winter approaching, the outlook was grim. F

aced with the suffering of her children, Akulina made a devastating choice. She chose to go without food so they might live, ultimately sacrificing her life for theirs.

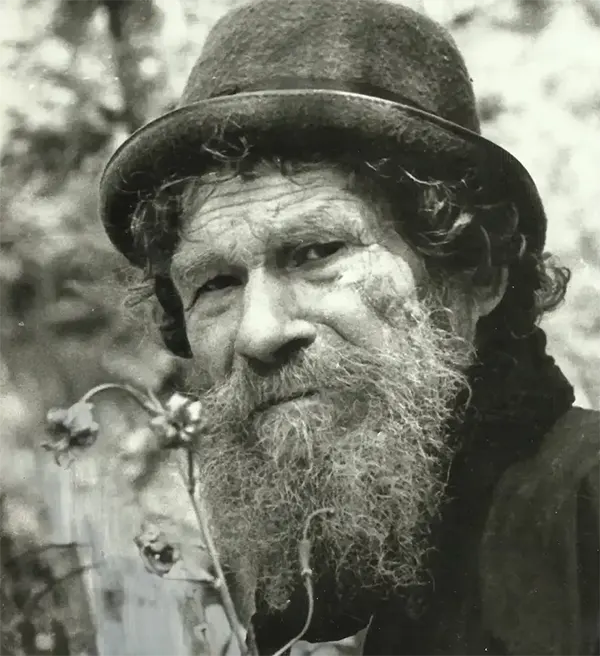

Photograph of Karp Lykov after relocating to the Siberian wilderness.

When the geologists learned of her death, they were visibly shaken. They offered to bring the family back to civilization—where warm homes, medical care, and food awaited—but the Lykovs declined.

The children knew almost nothing about the outside world. They had been raised to believe cities were places of sin and suffering, and the idea of leaving their home was deeply unsettling.

The family was unaware of the Second World War, of the nuclear age, or of the sweeping changes that had transformed the world in their absence. Time, for them, had stood still.

Although the geologists respected their wishes, they left the family with a few essentials: salt, grain, knives, forks, paper, a torch, and pens.

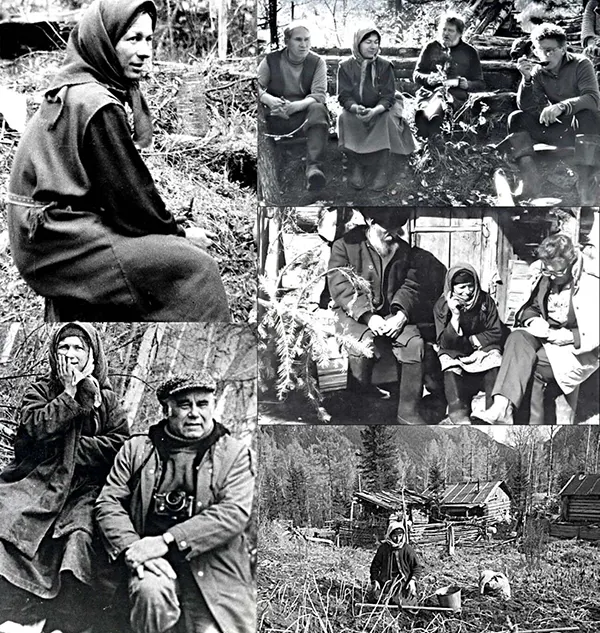

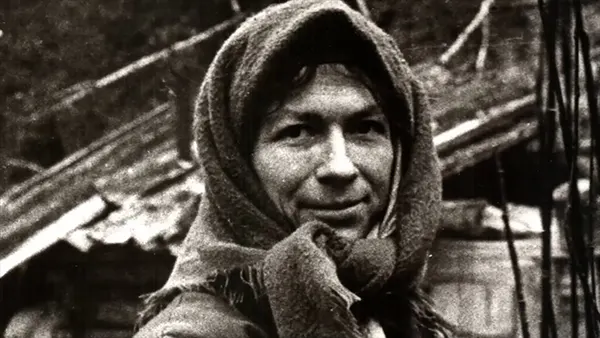

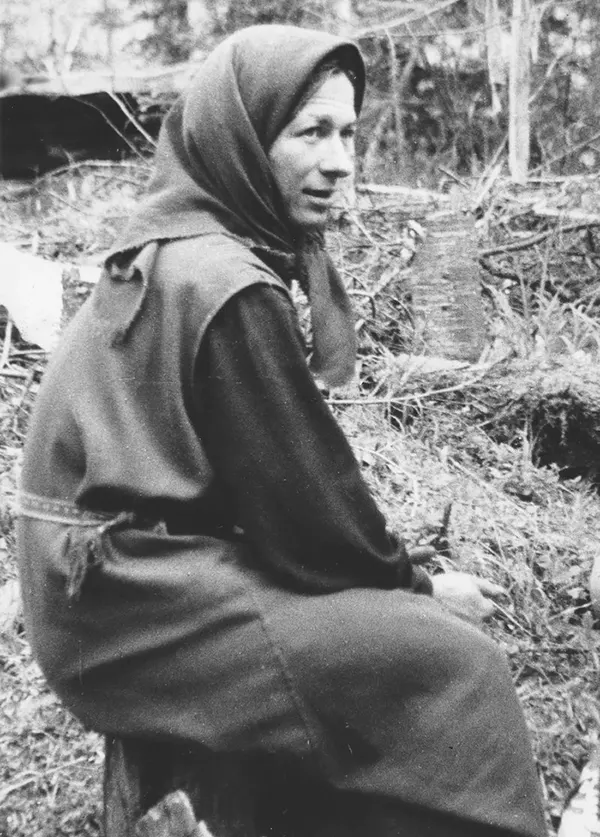

Photograph of Agafia Lykov.

Life After Discovery

The geologists resumed their mission but made regular visits to the Lykovs, who had grown close to them.

Multiple invitations to relocate were extended, yet the family chose to remain in their earthen cabin, where temperatures often stayed near freezing.

As mentioned above, in 1981, Savin, Natalia, and Dmitry passed away within days of each other. Karp and Agafia lived peacefully in the cabin until Karp died in 1988.

Photograph of Agafia Lykov.

After her father’s death, Agafia remained at the homestead, raising goats and tending to the small plot. She shared the cabin for 18 years with Yerofei Sedov, one of the geologists.

In an interview with VICE News, Agafia bluntly noted his lack of help and that she had to fetch water for him. Sedov died on May 3, 2015.

That same year, Agafia was joined by Georgy Danilov, a 53-year-old man from Orenburg who answered her public request for assistance. He moved to her remote dwelling and offered support where needed.

Agafia (left) and Natalia Lykov.

In 2016, Agafia was airlifted from her remote home to a hospital in Tashtagol due to severe joint issues in her legs, brought on by years of hard living.

She received treatment and later returned to the forest, where she remains as of 2024.

When asked her thoughts on city life, Agafia replied simply—there were “too many people” and “too many cars.”

Photograph of Agafia Lykov.

Photograph of Agafia Lykov.

Peskov’s report in Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper.

Agafia Lykova and journalist Vasily Peskov going across the Yerinat river, 2004. Photo by Vladimir Shelkov/TASS.

Photograph of Agafia Lykov.

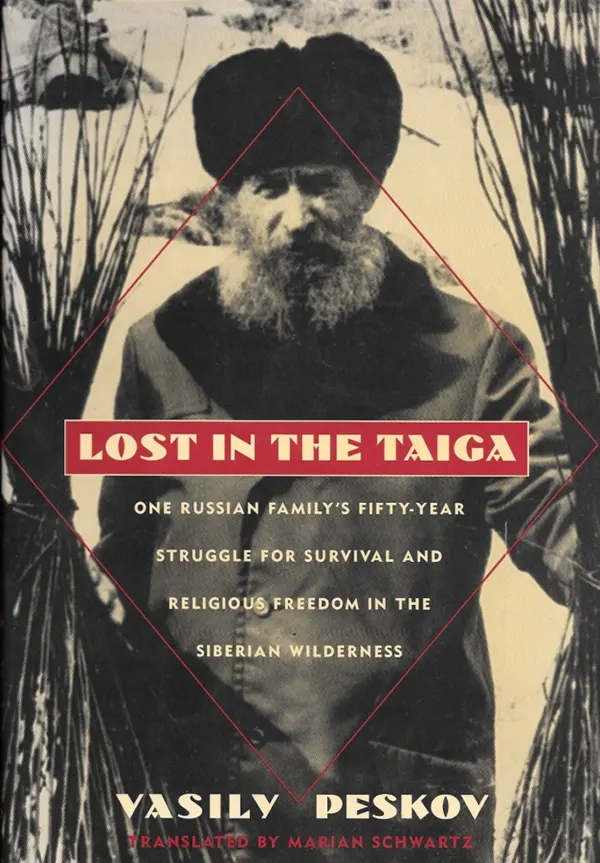

Lost in the Taiga. A Russian journalist provides a haunting account of the Lykovs, a family of Old Believers, or members of a fundamentalist sect, who in 1932 went to live in the depths of the Siberian Taiga.

(Photo credit: TASS / Wikimedia Commons / Yandex.ru / RHP).