In October 1963, a small tuxedo cat from the streets of Paris was chosen to do something no feline had ever done before. Her name was Félicette, and she would become the first cat launched into space.

At just five and a half pounds, she hardly seemed like the face of cutting-edge science. Yet her calm nature and light build made her the perfect candidate for a mission that would mark France’s bold entry into the Space Race.

For 15 dizzying minutes, Félicette soared into the skies aboard a French rocket, experiencing weightlessness before safely returning to Earth.

But while animals like Laika the dog and Ham the chimpanzee became symbols of the era, Félicette’s story faded into obscurity.

Today, her legacy is being rediscovered, thanks to rare photographs and a growing recognition of her unique place in history.

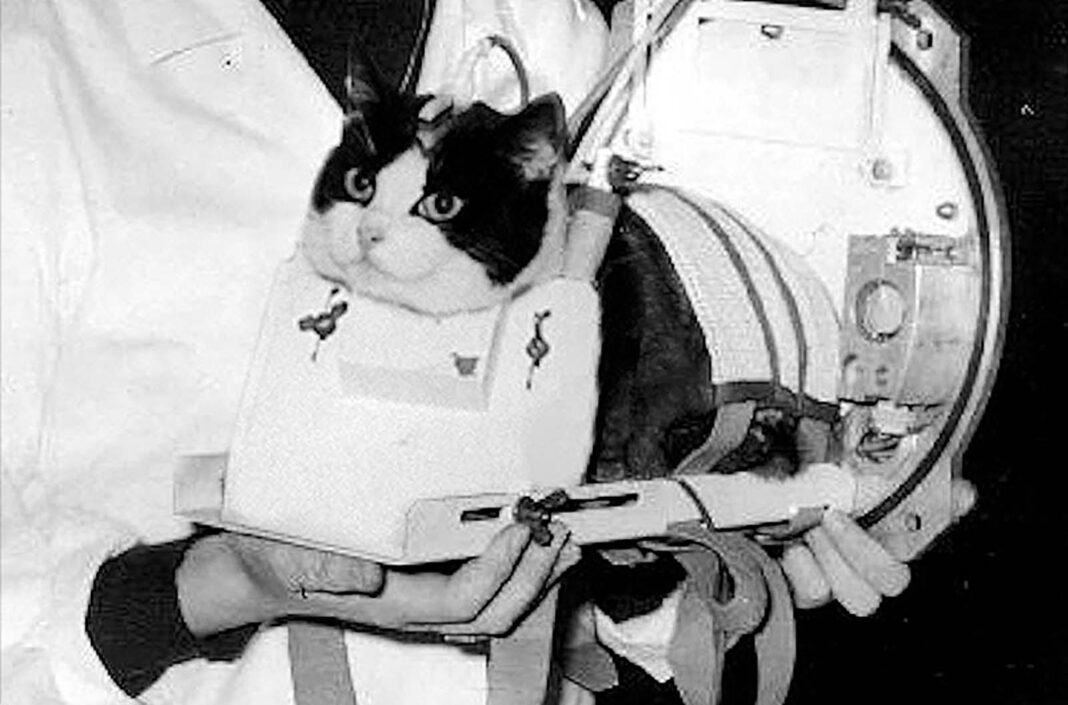

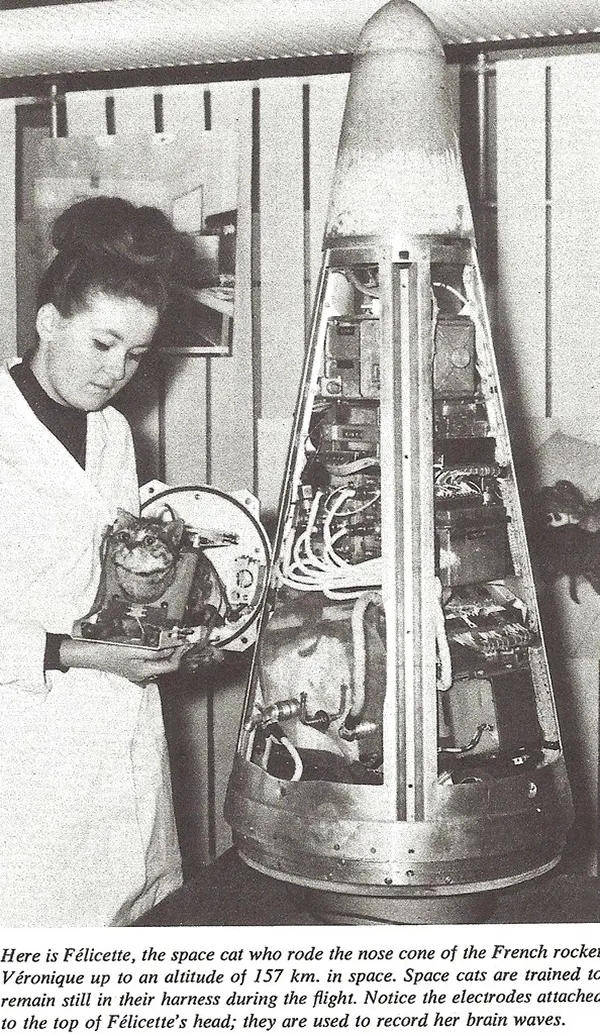

Félicette ready to launch into space.

Why France Chose Cats for Spaceflight

By the early 1960s, the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union had transformed space exploration into a global spectacle.

The Soviets had already sent Laika the dog into orbit in 1957, while the Americans followed with Ham the chimp in 1961.

France, meanwhile, had launched only rats—an achievement that felt modest compared to the feats of the superpowers.

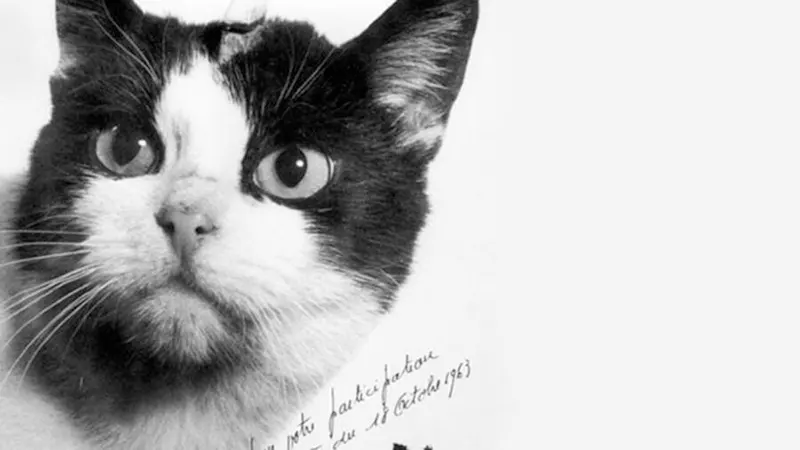

Image of Félicette with the implanted electrode visible on her forehead. Inscription: “Thank you for your participation in my success of 18 October 1963”

French scientists knew they needed test subjects that could provide better insights into human physiology during spaceflight.

Cats, already well-studied in neurological and behavioral research, seemed an ideal choice. In pursuit of this new direction, researchers at the CERMA acquired 14 female cats and began preparing them for the unknown.

One of them, identified only as “C 341,” would later be remembered by a very different name: Félicette.

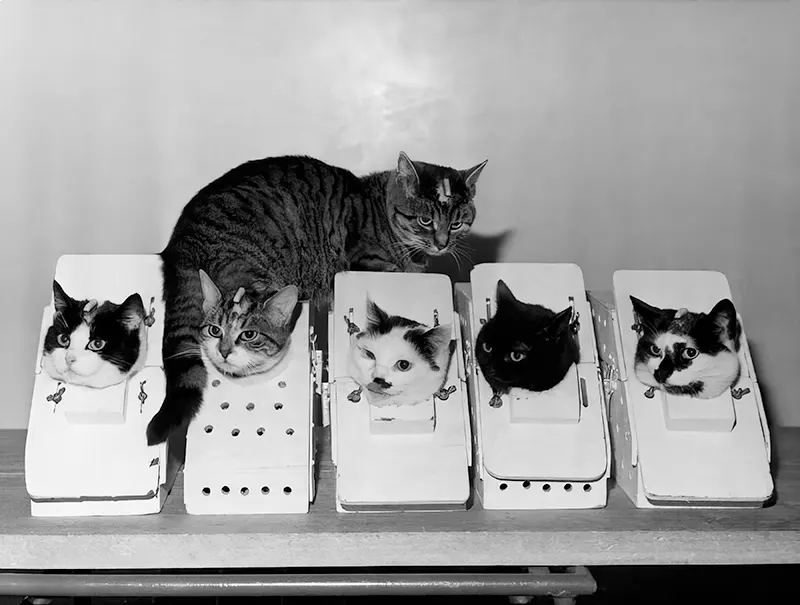

Several of the cats “trained” to go to space, including Félicette at far left.

Training the Feline Astronauts

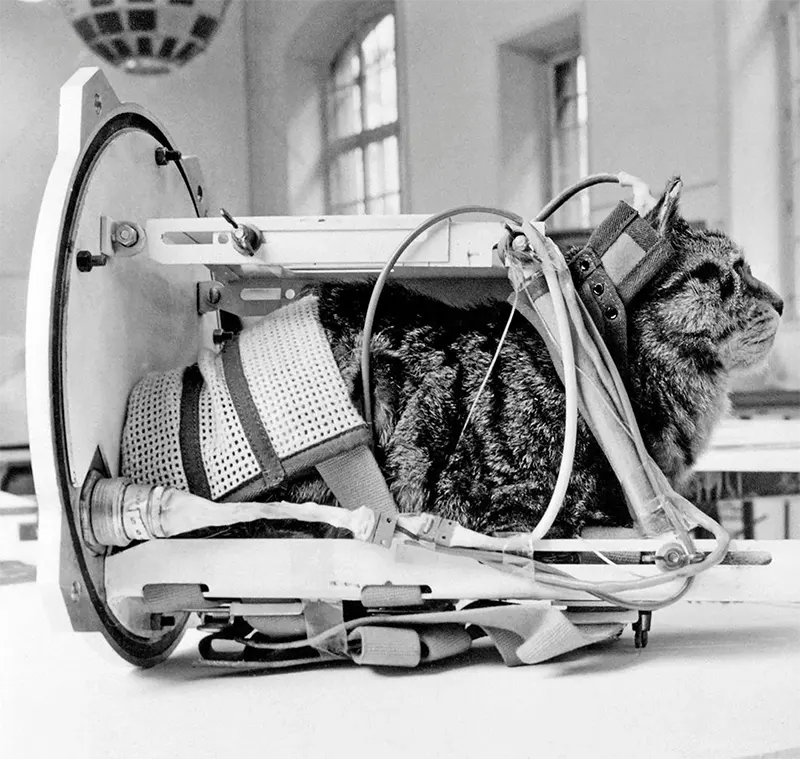

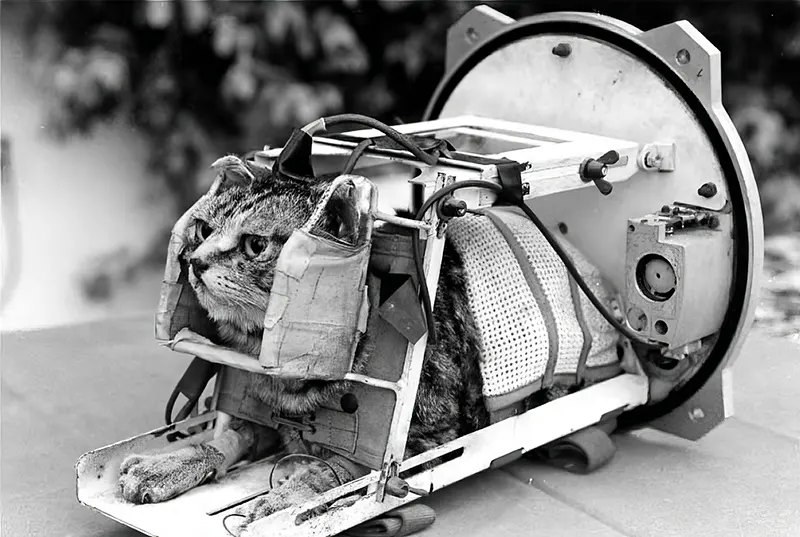

The training program for France’s feline astronauts was rigorous and, at times, unsettling. Electrodes were surgically implanted in the cats’ brains to allow scientists to monitor neurological activity.

Over several months, they were subjected to confinement, loud rocket simulations, and high-G centrifuge rides that mimicked the crushing acceleration of launch.

The cats also endured specialized exercises, such as sitting in restraint cloths and being placed in containers designed to simulate the capsule environment.

These conditions mirrored, in scaled-down fashion, the training human astronauts faced at the time.

These conditions mirrored, in scaled-down fashion, the training human astronauts faced at the time.

Scientists deliberately refrained from naming the animals to avoid attachment, though this detachment would not last.

Among the group, one tuxedo cat distinguished herself with calmness and resilience—qualities that would secure her place on the mission.

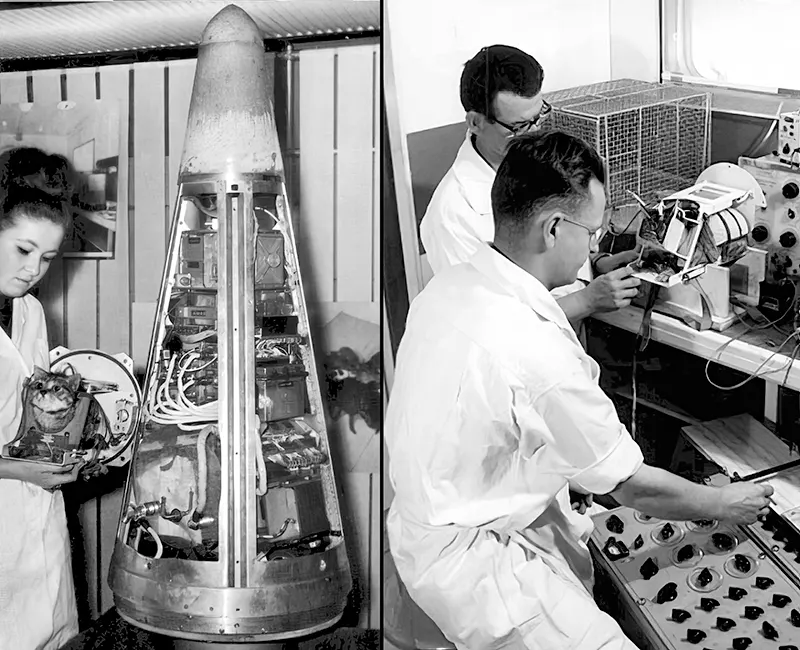

Training and preparing the equipment. A cat can be seen in one of the containers.

Launching Félicette Into Space

By mid-October 1963, six cats remained in the final pool of candidates. On October 17, researchers selected C 341—soon to be known as Félicette—as the primary astronaut, with another feline as her backup.

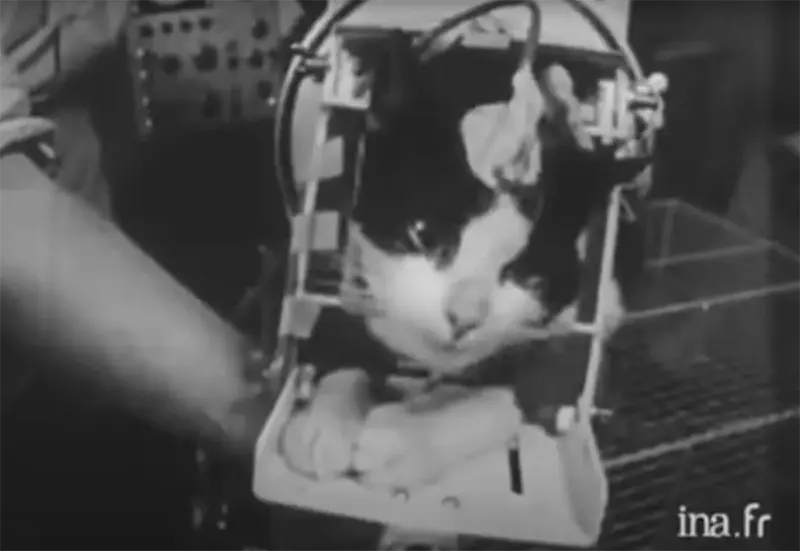

At 8:09 a.m. on October 18, 1963, a Véronique AGI 47 sounding rocket lifted off from a launch site in Algeria, carrying Félicette on a suborbital mission.

The rocket’s engine burned for 42 seconds, subjecting her to nearly 10 times the force of gravity.

Félicette after landing back on Earth.

After separating from the main body, her capsule continued upward to an altitude of 152 kilometers (94 miles), where she floated in weightlessness for about five minutes.

During the flight, sensors monitored her heart rate, breathing, and brain activity through implanted and external electrodes, while microphones inside the capsule captured the sounds of her respiration.

The mission lasted 13 minutes in total before the capsule descended under parachute and was safely recovered. Against all odds, Félicette returned alive, officially securing her place in space history.

Scientists load a container with Félicette into the capsule.

The Aftermath of the Mission

Despite her success, Félicette’s story took a tragic turn. Two months after her return, scientists euthanized her to study her brain and analyze the effects of spaceflight in greater detail.

While her data provided useful insights, it also raised ethical questions. Of the 14 cats originally trained, 11 were ultimately euthanized at the conclusion of the program.

One exception was a cat affectionately nicknamed Scoubidou, who became a mascot for the researchers after complications forced the removal of her electrodes.

Legacy and Recognition

Félicette’s flight marked a major milestone for France, which had just established the world’s third civilian space agency, behind only the Soviet Union and the United States.

Her mission helped elevate French contributions to space research, but her fame never reached the level of other spacefaring animals.

The sight of photographs showing electrodes implanted in her skull, combined with the growing animal rights movement, likely contributed to her quiet place in history.

A cat from the program fitted into the monitoring container.

Yet her contribution was not forgotten entirely. Several nations, including former French colonies such as Comoros, Chad, and Niger, later issued postage stamps depicting Félicette—though many mistakenly labeled her as “Félix.”

For decades, however, there was no official monument honoring her sacrifice. That changed in 2017, when a crowdfunding campaign spearheaded by Matthew Serge Guy successfully raised funds for a memorial.

British sculptor Gill Parker created a bronze statue of Félicette, which was unveiled in December 2019 at the International Space University in Strasbourg, France.

One of the many cats shortlisted for the flight, strapped to a restraining apparatus that would be used on rocket flight.

Félicette in her container. Still from the official video.

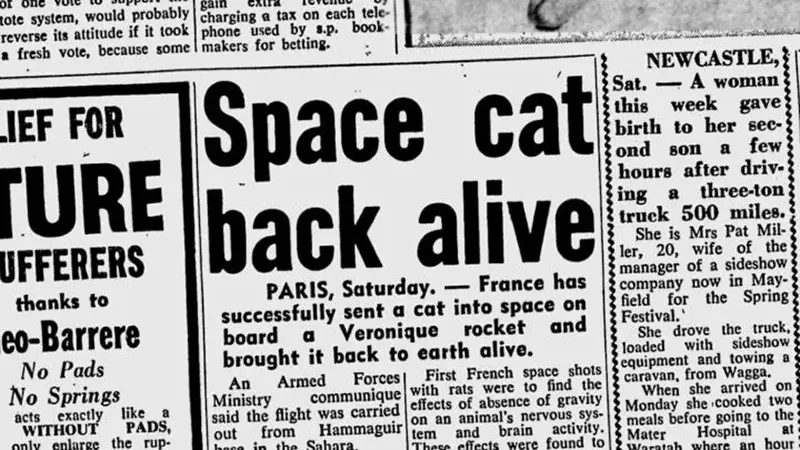

A screenshot taken from a newspaper.

The Sydney Morning Herald (October 20, 1963).

A stamp erroneously honoring “Félix” the cat.

(Photo credit: RHP / Wikimedia Commons / Pinterest / Flickr).