Before the internet made it effortless to delete a name, block a profile, or erase a face from the digital record, “unfriending” looked very different.

It was a messy, physical act that required scissors, ink, or whatever tools were at hand. A falling out with a friend, the end of a romance, or a bitter family dispute could all leave their mark not just on memories, but directly on the photographs that preserved them.

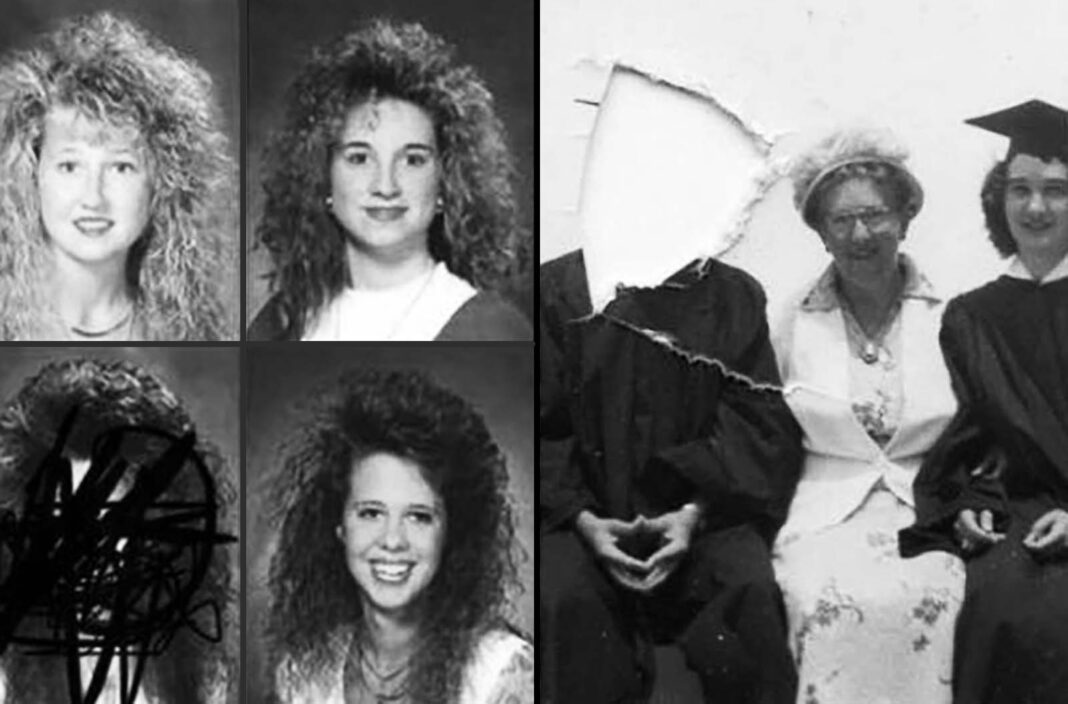

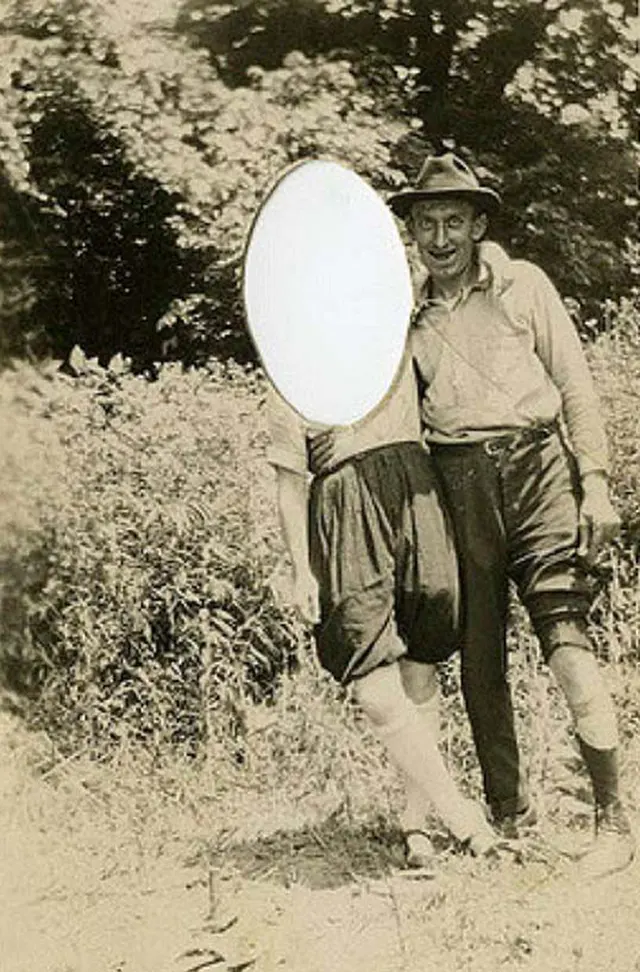

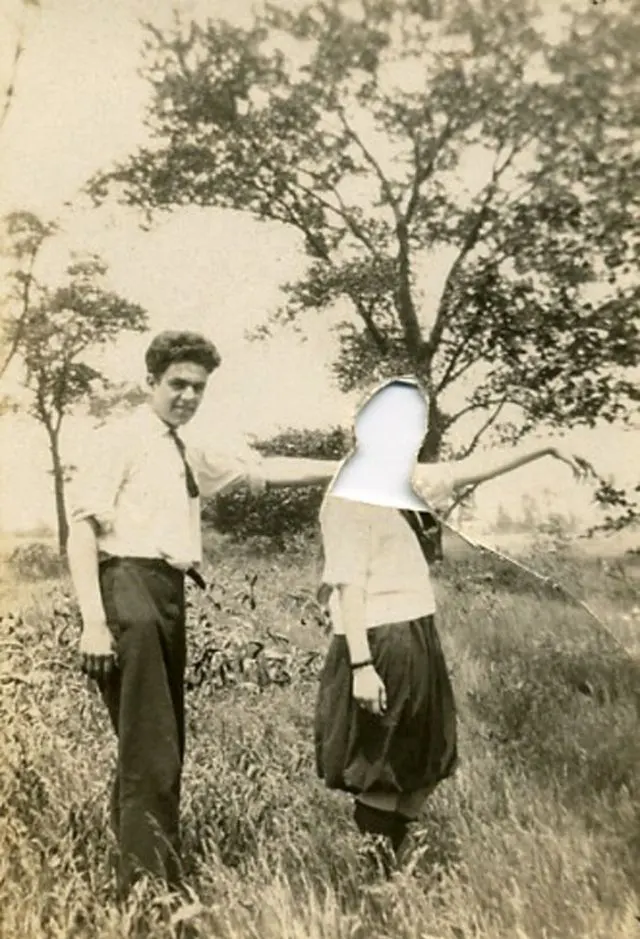

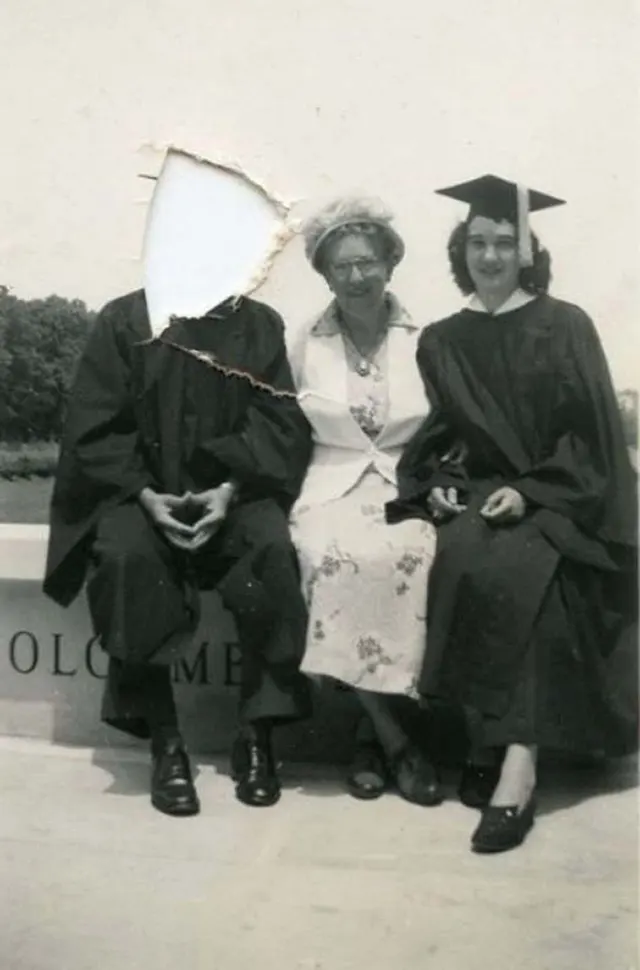

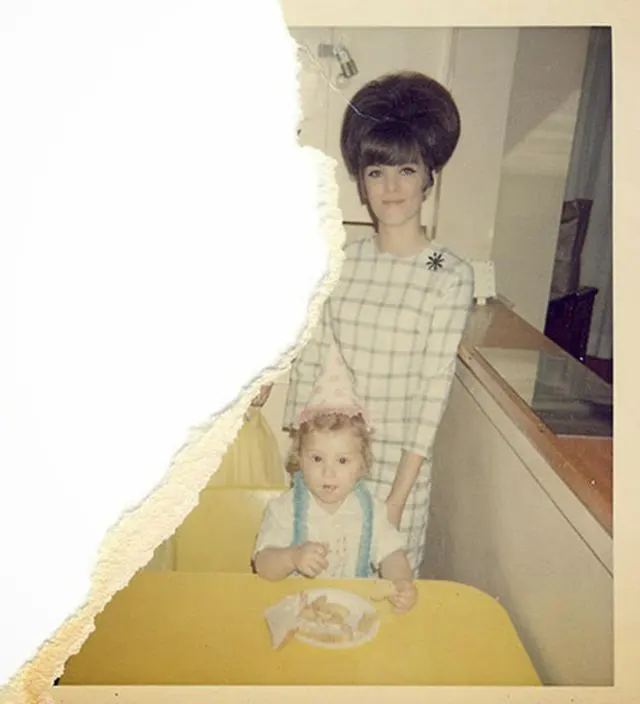

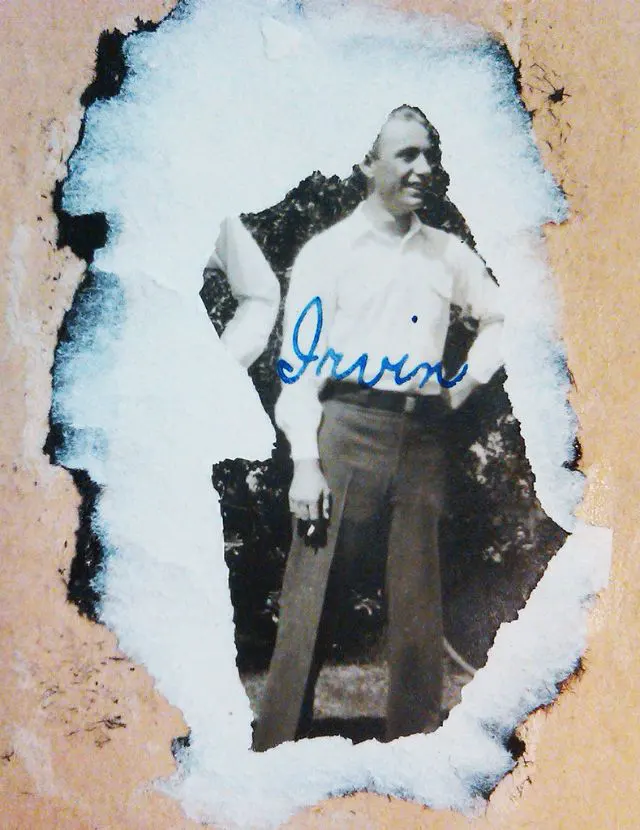

Cutting ties often meant literally cutting people out. Some would carefully trim around a figure, leaving the rest of the photo intact but with an empty gap where a familiar face once smiled.

Others were less precise, hacking out entire portions of the image so that a body or group shot looked strangely incomplete.

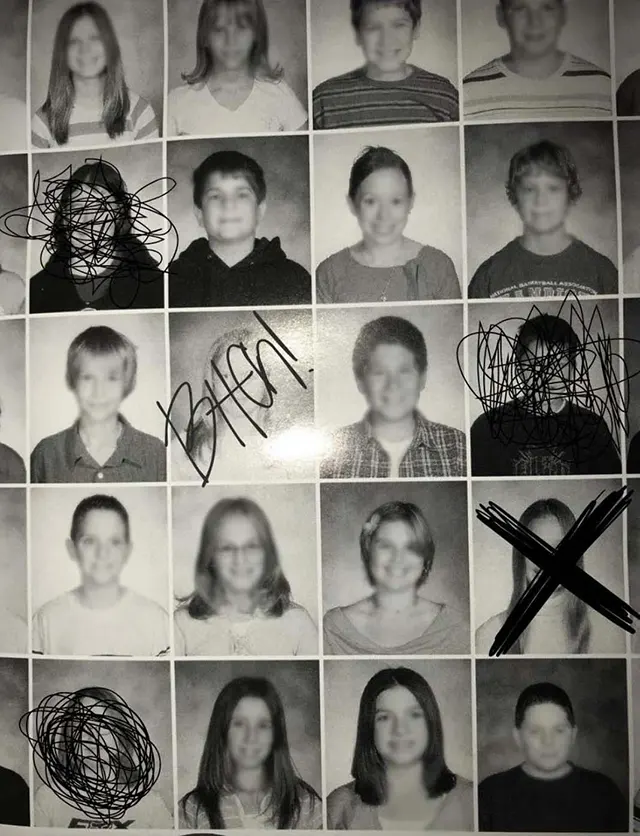

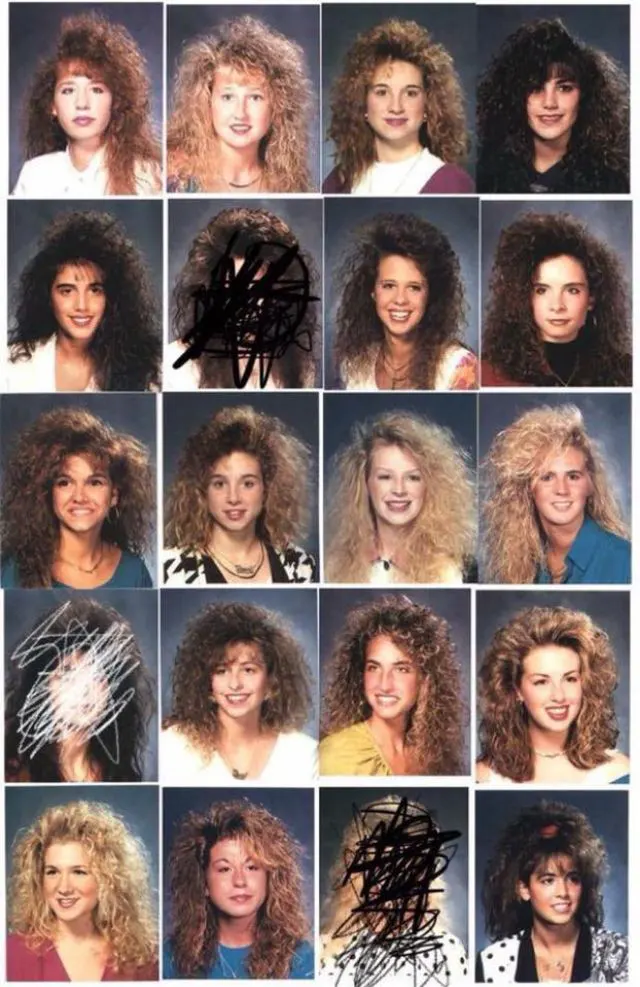

Ink was another popular weapon. Black stains blotted out unwanted faces with a kind of finality that scissors couldn’t achieve, sometimes spreading across the photograph like a shadow.

Ink was another popular weapon. Black stains blotted out unwanted faces with a kind of finality that scissors couldn’t achieve, sometimes spreading across the photograph like a shadow.

In other cases, the erasure was more deliberate and almost performative—crossing someone’s face with a thick pen stroke, scribbling over their head in frustration, or scratching until the surface of the photo was permanently scarred.

There were subtler methods, too. Some people blurred a figure by smudging the print, leaving behind a ghostly outline instead of a clear portrait.

There were subtler methods, too. Some people blurred a figure by smudging the print, leaving behind a ghostly outline instead of a clear portrait.

Others wrote over a person’s face with angry notes or mocking words, transforming the photograph into a personal statement as much as a keepsake.

Even a simple line drawn through someone’s image carried a sharp message: this person no longer belonged in the frame of memory.

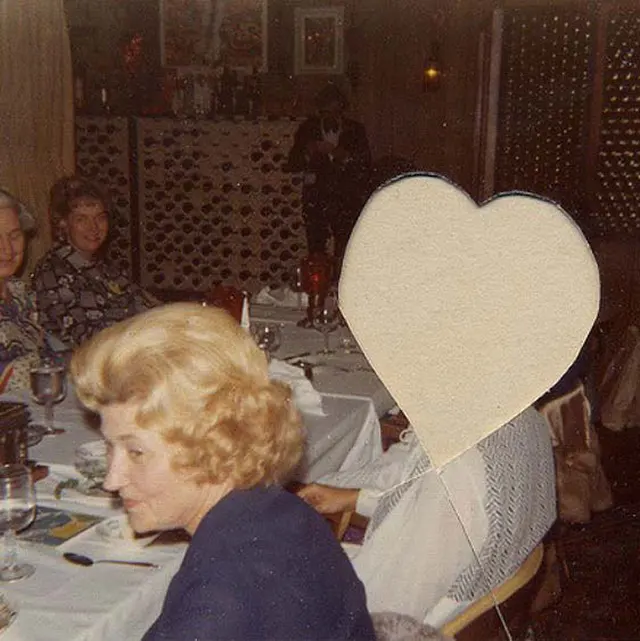

Looking back, these altered photographs offer more than just curiosity value. They are reminders of how seriously people once treated the images they kept.

Looking back, these altered photographs offer more than just curiosity value. They are reminders of how seriously people once treated the images they kept.

Unlike today, when thousands of pictures can be stored and deleted with a tap of a finger, every photograph once mattered.

To take the time to destroy or disfigure one was to make a statement, however small, about memory, belonging, and loss.

(Photo credit: RHP / Flickr via RHP).