During the depths of the Great Depression, American cities witnessed mass expulsions that would tear apart families and communities for generations.

Between 1929 and 1939, somewhere between 300,000 and 2 million people of Mexican descent were forced or pressured to leave the United States—and shockingly, forty to sixty percent of them were American citizens, predominantly children.

While the federal government supported these actions, the driving force behind the Mexican Repatriation came primarily from city and state authorities, often backed by local private organizations.

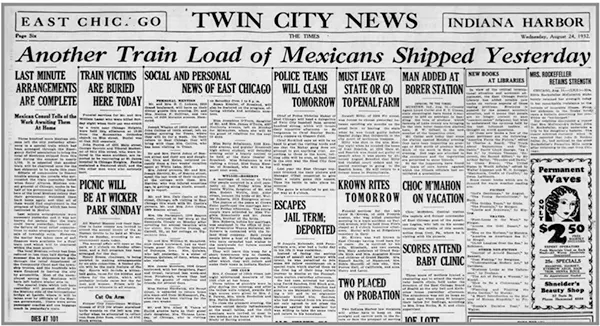

People of Mexican descent, including U.S.-born citizens, were put on trains and buses and deported to Mexico during the Great Depression.

Voluntary departure vastly outnumbered formal deportations, with federal officials playing a surprisingly minimal role in the process.

Many people left hoping to escape the economic devastation gripping the nation. The government formally deported at least 82,000 individuals, with the overwhelming majority of these deportations concentrated between 1930 and 1933.

Mexico itself encouraged this exodus, enticing returnees with promises of free land.

Mexicans travel back to Mexico after being deported from Los Angeles in 1931.

Scholars argue that the surge in deportations during this period reflected a deliberate policy under President Herbert Hoover’s administration, which had adopted increasingly restrictive immigration measures.

Hoover first referenced this approach in his 1930 State of the Union Address, setting the stage for what would become the peak years of forced removal.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1933, his administration relaxed immigration enforcement, leading to a notable decline in both formal and voluntary departures.

Illegal immigrants being escorted back across the border to Mexico.

As scapegoats for the Great Depression’s economic catastrophe, Mexican workers found themselves systematically stripped of employment opportunities.

Their targeting intensified due to what historians describe as “the proximity of the Mexican border, the physical distinctiveness of mestizos, and easily identifiable barrios.”

While estimates vary widely—from 300,000 to 2 million people moved to Mexico during this decade—most researchers place the figure between 500,000 and 1 million.

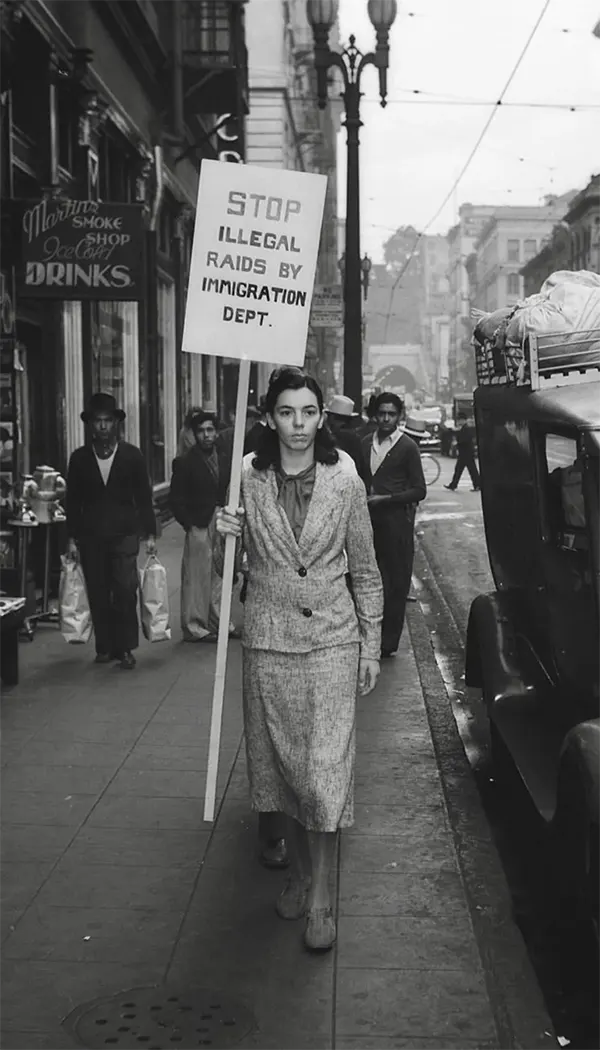

A lone woman picketing against immigration raids in 1937, Los Angeles, USA

The highest numbers come from contemporary Mexican press accounts. The exodus peaked dramatically in 1931, with the vast majority of removals occurring in the early years of the Depression.

Census data reveals the impact: the Mexican-origin population in the United States dropped from approximately 1,692,000 in 1930 to 1,592,000 by 1940. By 1934, up to one-third of all Mexicans living in the United States had been repatriated.

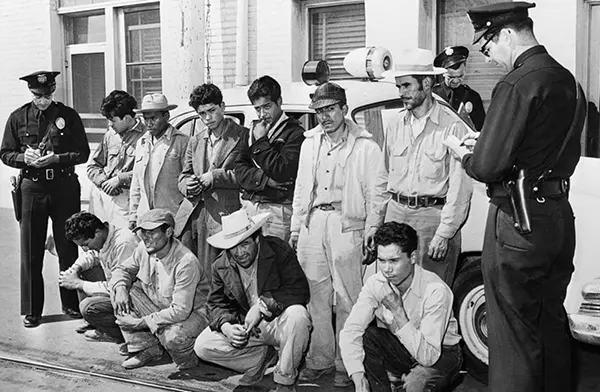

A group of Mexicans who were taken off freight trains in Los Angeles, after two days without food or water, in 1953.

The methods employed during these operations were particularly disturbing. In Los Angeles, immigration raids swept through neighborhoods, with agents and deputies sealing off entire districts.

In East Los Angeles, authorities descended on Mexican communities, “riding around the neighborhood with their sirens wailing and advising people to surrender themselves to the authorities.”

The raids often netted hundreds of people at once, with all escape routes deliberately blocked.

Agricultural workers of Mexican descent await deportation in 1950 in California.

Those detained faced a deeply flawed legal process. While requesting a hearing remained technically possible, immigration officers routinely failed to inform individuals of this right.

The hearings themselves were “official but informal,” with immigration inspectors simultaneously serving as “interpreter, accuser, judge, and jury.”

Legal representation was rare, available only at the discretion of the immigration officer handling the case.

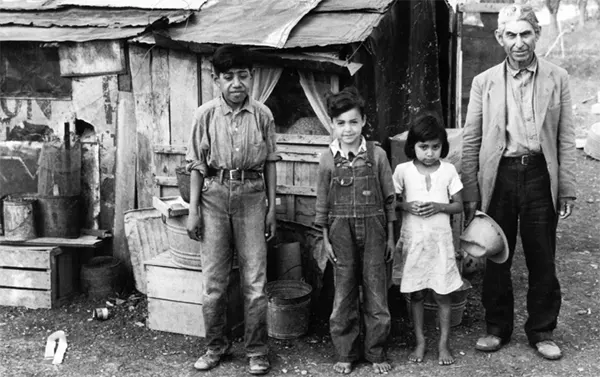

The Vigues, an immigrant family from Mexico, stand outside their dilapidated shack in Austin, Texas, in the early 1940s.

This entire process likely violated fundamental constitutional protections, including federal due process guarantees, equal protection principles, and Fourth Amendment rights.

For those apprehended who chose not to request a hearing, voluntary self-deportation presented itself as an alternative.

In theory, this option would preserve their ability to return legally to the United States later, since “no arrest warrant was issued and no legal record or judicial transcript of the incident was kept.”

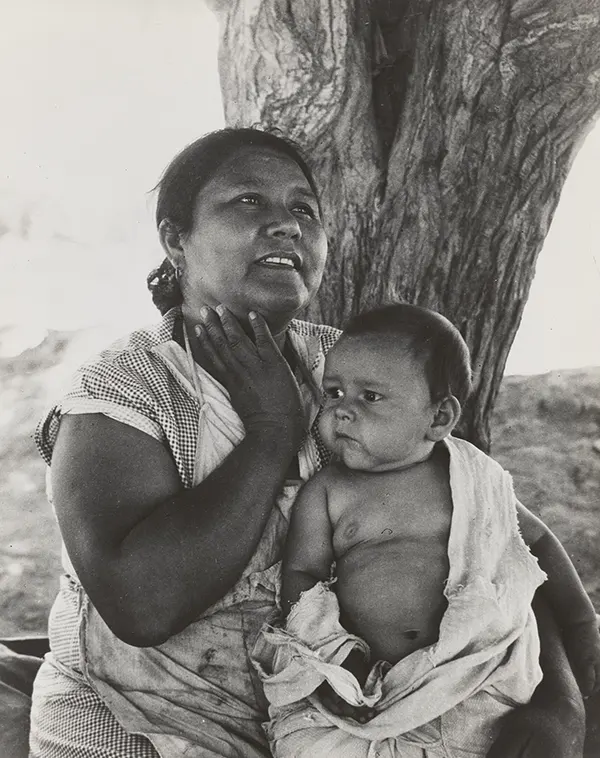

California mother describes voluntary repatriation: “Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me, ‘We don’t want to go, we belong here.’” (1935 photograph by Dorothea Lange).

However, many people were deceived. Upon departure, they received a “stamp on their card [which showed] that they have been county charities”—a designation that would bar their readmission on grounds that they would be “liable to become a public charge.”

Decades would pass before any official acknowledgment of these injustices emerged.

People waving goodbye to a train departing Los Angeles with 1,500 Mexicans on August 20, 1931.

In 2006, Congressional representatives Hilda Solis and Luis Gutiérrez introduced legislation calling for a commission to examine this dark chapter, with Solis also advocating for a formal apology.

California had already taken a significant step the previous year, passing the “Apology Act for the 1930s Mexican Repatriation Program” in 2005.

Mexicans aliens on the road with tire trouble (California, 1936).

This landmark legislation officially recognized the “unconstitutional removal and coerced emigration of United States citizens and legal residents of Mexican descent”.

It apologized to California residents “for the fundamental violations of their basic civil liberties and constitutional rights committed during the period of illegal deportation and coerced emigration.”

Mexican citizens entering the United States at an immigration station in El Paso, Texas, 1938.

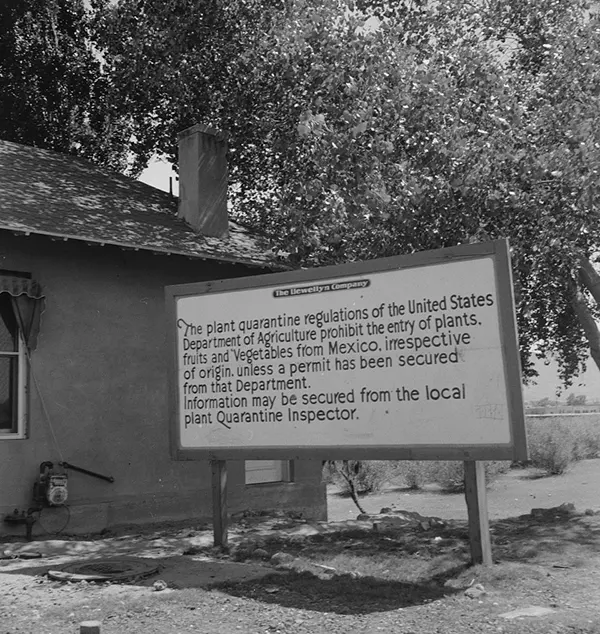

Sign at bridge between Juarez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas. (1937)

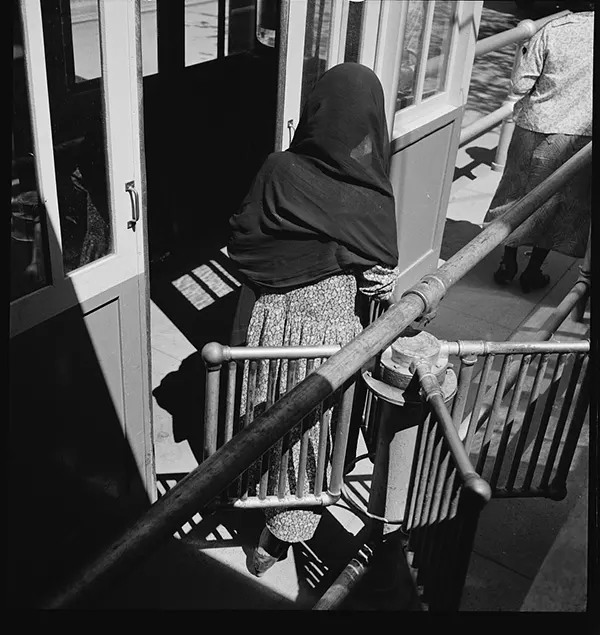

Mexican woman entering the United States. United States immigration station, El Paso, Texas. (1938)

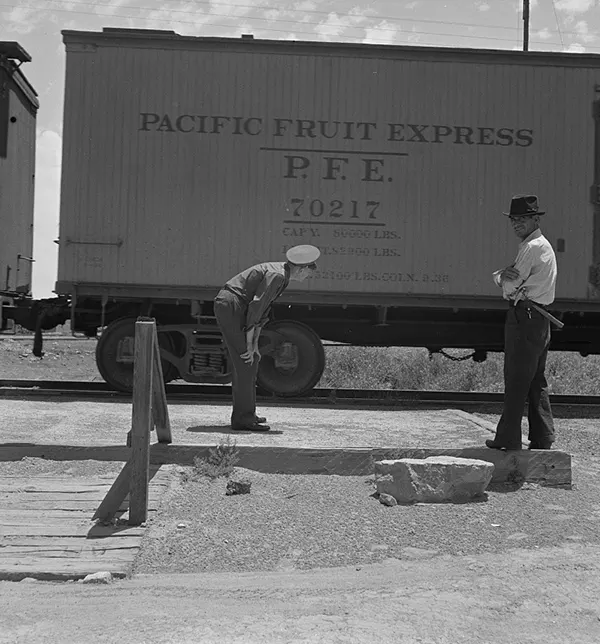

Inspecting a freight train from Mexico for smuggled immigrants. El Paso, Texas. (1937)

Emilio Cabrera and his wife Maria Asuncion in 1934. Although a U.S. citizen, Cabrera was deported to Mexico at age 12, but later returned.

Two armed American border guards deter a group of illegal immigrants from attempting to cross a river from Mexico into the United States on 1 January 1948.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Britannica / Flickr).