The summer of 1967 marked a pivotal moment in American cultural history when San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district became the epicenter of a transformative social movement.

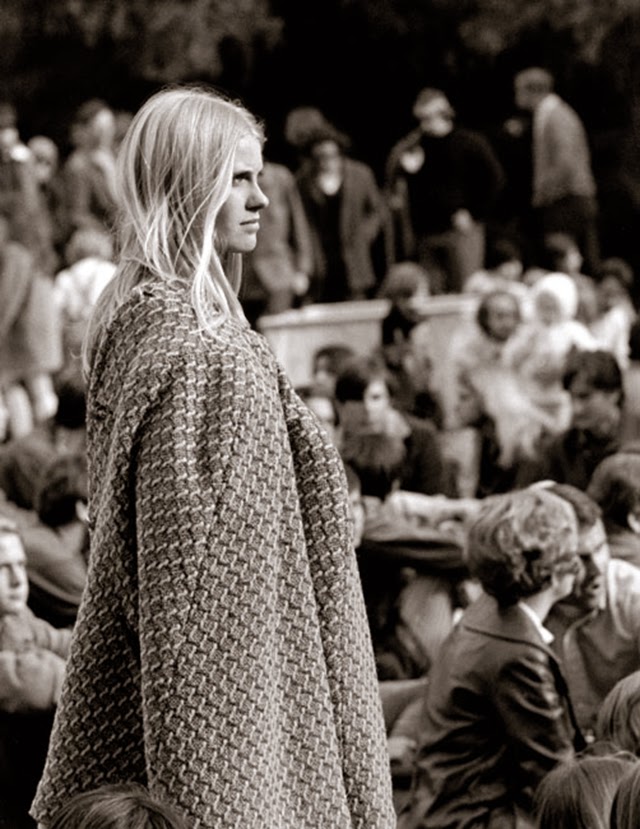

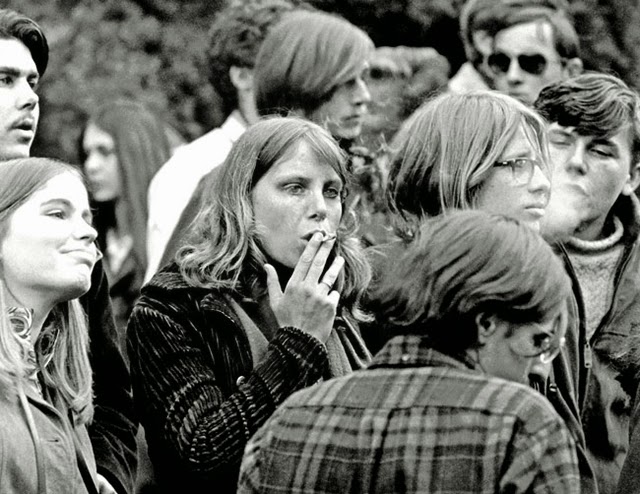

Nearly 100,000 young people—hippies, beatniks, and counterculture pioneers—descended upon this neighborhood and Golden Gate Park, creating what would become known as the Summer of Love.

This massive convergence represented one of the largest youth migrations in American history, rippling across the West Coast and reaching as far as New York City with its message of peace, spiritual awakening, and social revolution.

The roots of this phenomenon stretched back to the post-World War II era, when the Beat Generation first challenged mainstream American values.

The roots of this phenomenon stretched back to the post-World War II era, when the Beat Generation first challenged mainstream American values.

Writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, dubbed “hip” for their embrace of jazz culture, established a bohemian presence in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood.

These literary rebels paddled against the currents of materialistic society, though ironically, they too would eventually be absorbed by the popular culture they opposed.

As the 1960s progressed, this countercultural spirit migrated south to Haight-Ashbury, where it evolved into the hippie movement.

As the 1960s progressed, this countercultural spirit migrated south to Haight-Ashbury, where it evolved into the hippie movement.

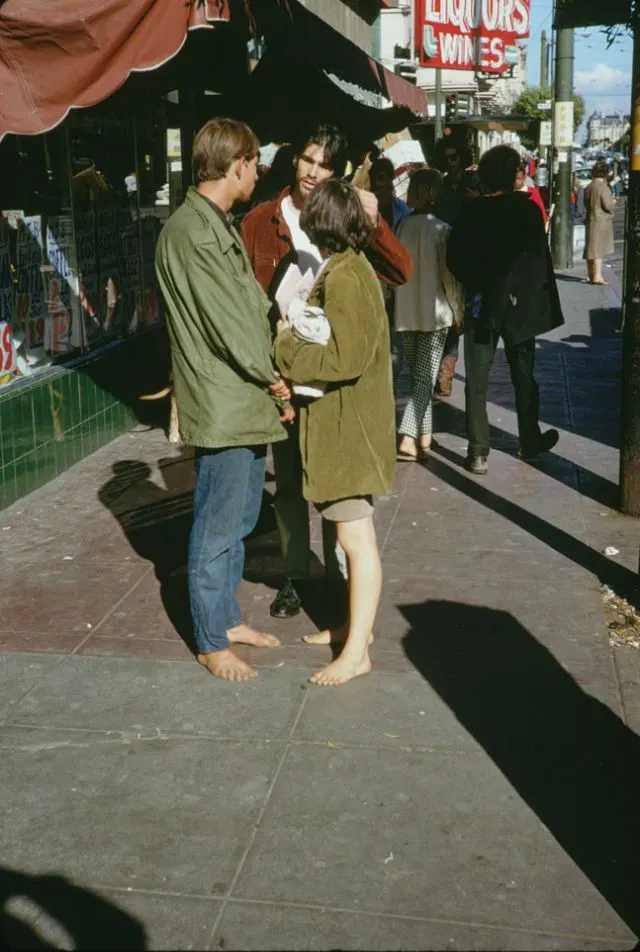

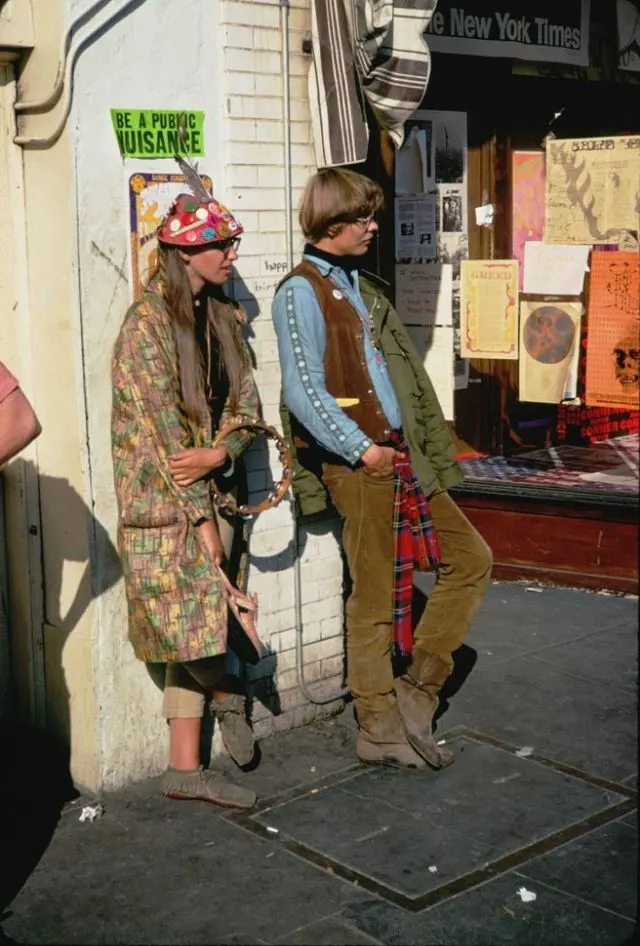

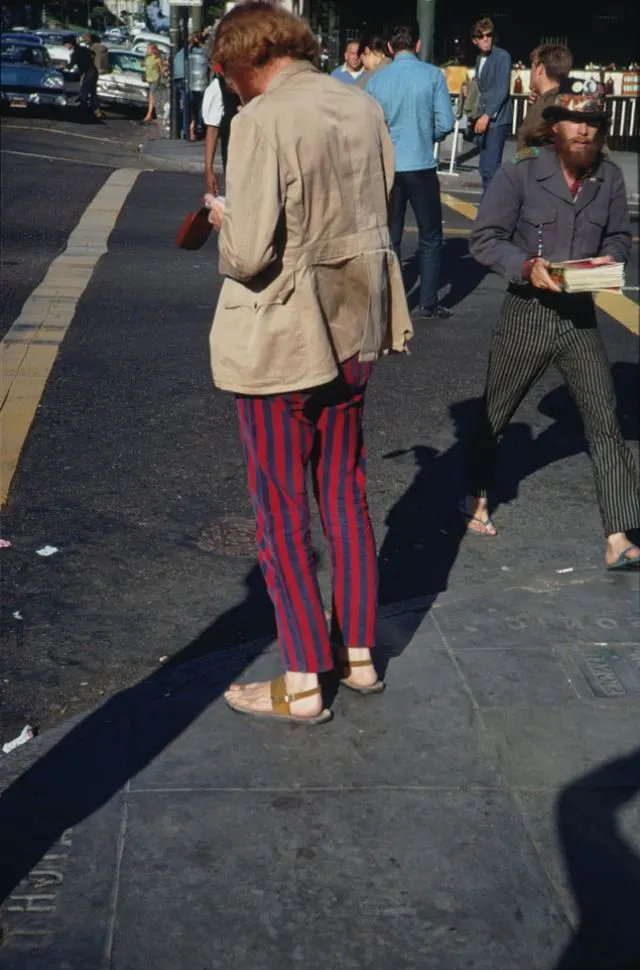

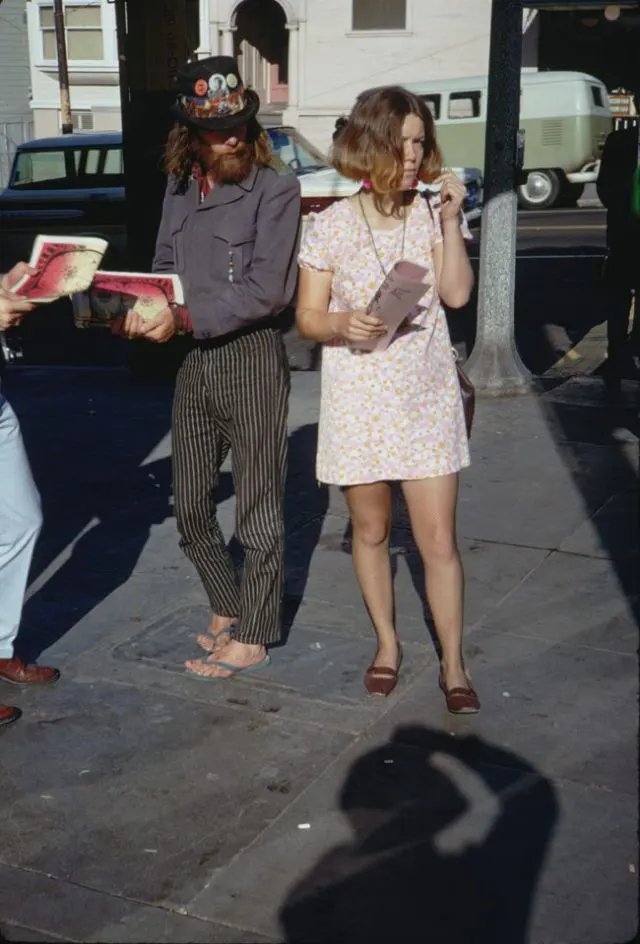

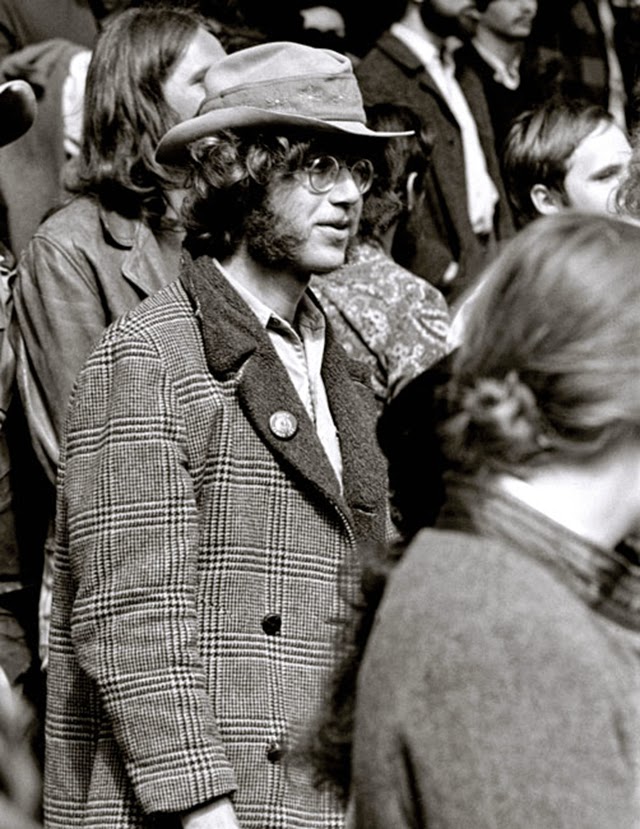

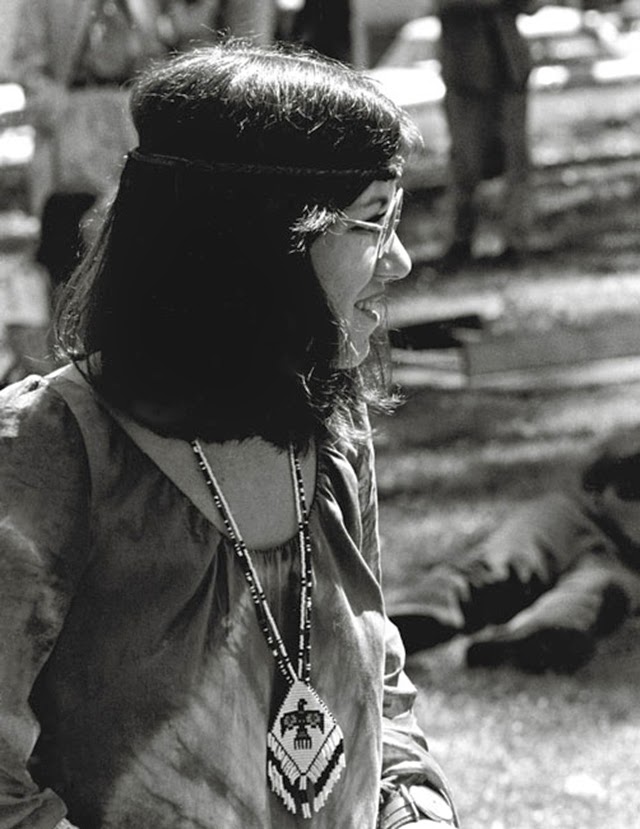

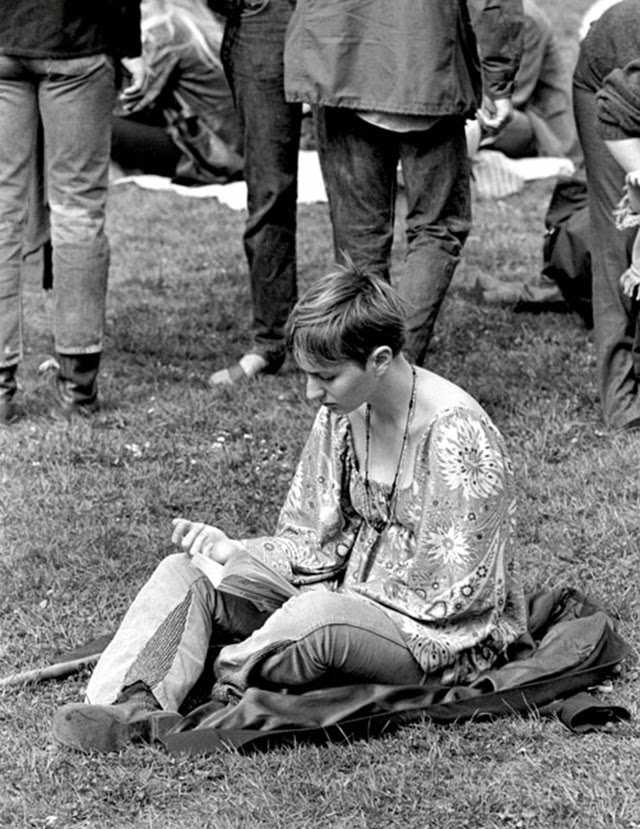

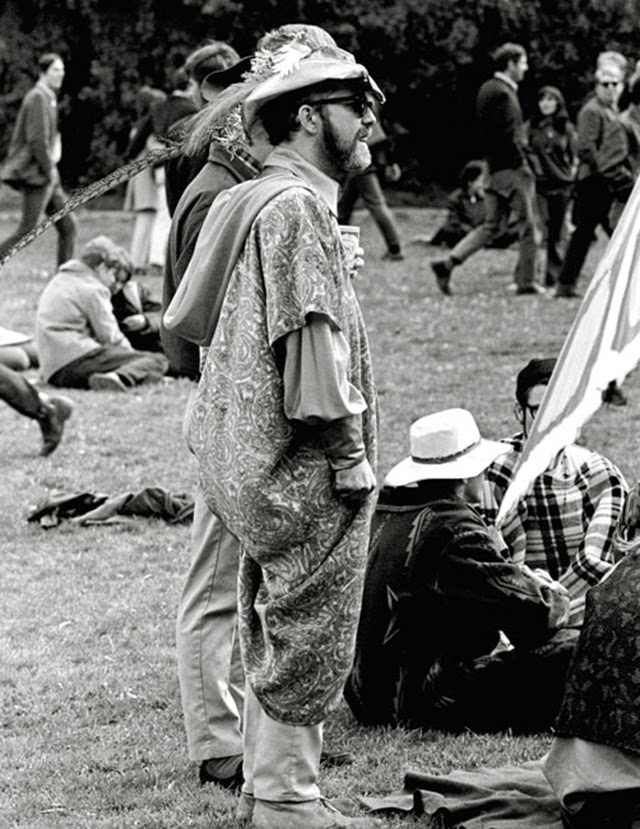

The flower children, as hippies were affectionately called, formed a diverse and eclectic community united by shared values rather than uniform beliefs.

These young people rejected the Vietnam War, questioned governmental authority, and turned their backs on consumerist culture.

Suburban conformity and conventional American lifestyles held no appeal; instead, they gravitated toward communal living arrangements and alternative ways of being.

Suburban conformity and conventional American lifestyles held no appeal; instead, they gravitated toward communal living arrangements and alternative ways of being.

While some channeled their dissent into political activism and organization, others found expression through artistic pursuits—music, painting, and poetry became vehicles for their vision.

Many explored Eastern philosophies, drawing inspiration from Hinduism and Buddhism to inform their spiritual practices and meditative disciplines.

Psychedelic drug culture formed an inseparable thread in the fabric of hippie life. LSD, commonly known as acid, held a particularly sacred status within the community.

Psychedelic drug culture formed an inseparable thread in the fabric of hippie life. LSD, commonly known as acid, held a particularly sacred status within the community.

Believers claimed these hallucinogenic experiences induced euphoric states and visions of “cosmic oneness,” fostering profound connections to the universe and all living things.

Novelist Ken Kesey, fresh from his success with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, pioneered San Francisco’s “acid tests” beginning in 1965, events that would define the psychedelic experience.

Marijuana and cocaine also circulated through hippie circles, though notably, alcohol—the drug of choice in mainstream America—remained largely absent from their gatherings.

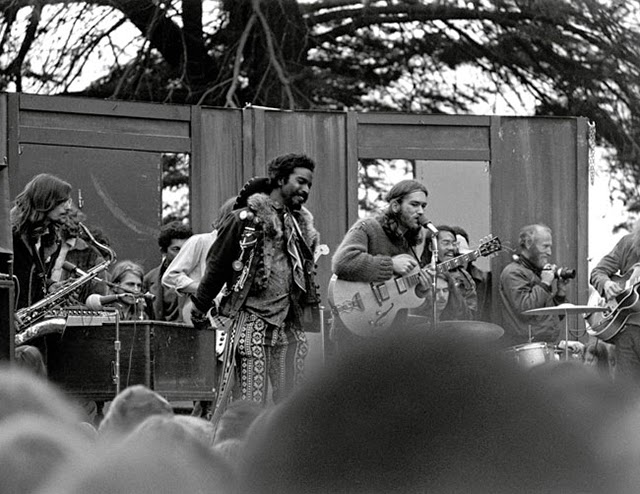

This chemical exploration catalyzed extraordinary creative output. Under the influence of LSD and other substances, hippies pioneered psychedelic light shows that transformed ordinary spaces into kaleidoscopic wonderlands.

This chemical exploration catalyzed extraordinary creative output. Under the influence of LSD and other substances, hippies pioneered psychedelic light shows that transformed ordinary spaces into kaleidoscopic wonderlands.

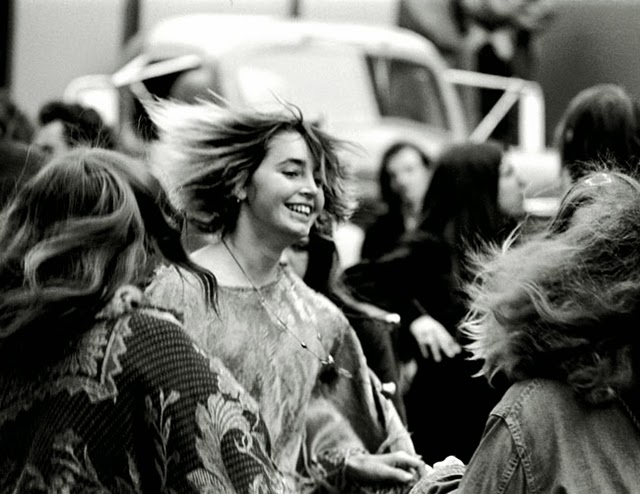

New dance forms emerged spontaneously, while musicians developed improvisational genres like “fo-jazz,” blending folk traditions with jazz sensibilities.

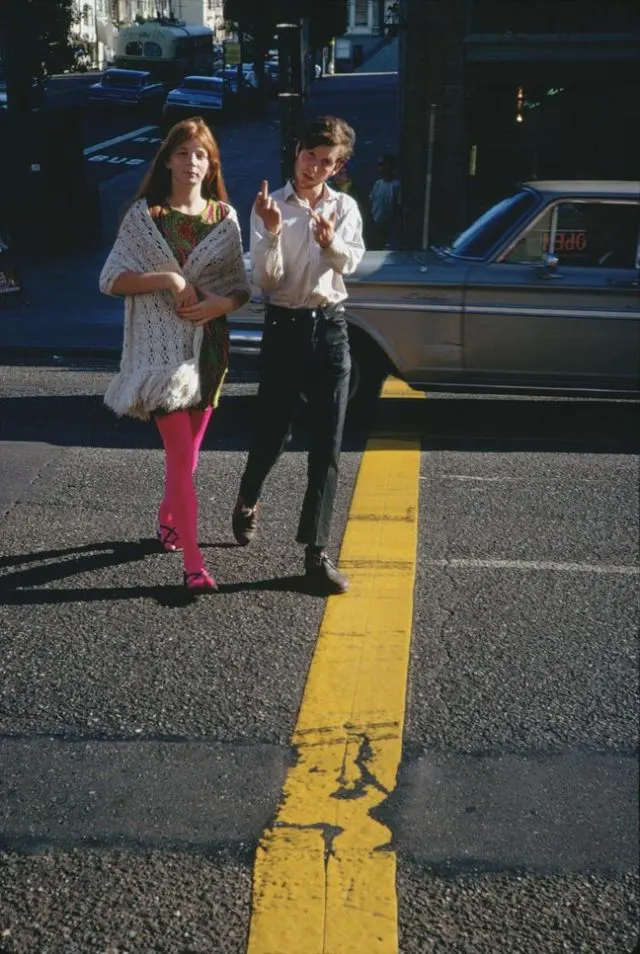

Fashion became a statement of rebellion, with vibrant colors and unconventional designs challenging conservative dress codes.

Poster art flourished, capturing the movement’s aesthetic in eye-catching designs that remain iconic today.

Poster art flourished, capturing the movement’s aesthetic in eye-catching designs that remain iconic today.

The subculture expanded beyond mere artistic expression, intertwining spirituality with radical politics.

Groups like the Diggers exemplified this fusion—they were actor-anarchists and community organizers who championed anti-capitalist principles and challenged establishment power structures throughout Haight-Ashbury’s multifaceted youth movement.

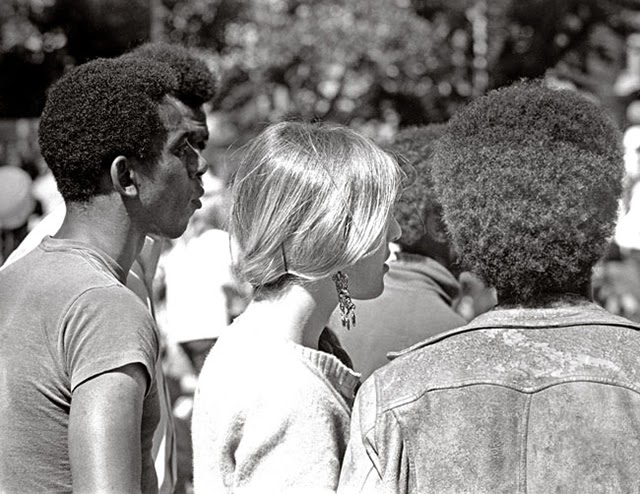

The summer of 1967 revealed a nation fractured along multiple fault lines. While San Francisco celebrated love and unity, other American cities burned during what became known as the “long, hot summer.”

The summer of 1967 revealed a nation fractured along multiple fault lines. While San Francisco celebrated love and unity, other American cities burned during what became known as the “long, hot summer.”

Civil rights activists fought desperately for equality and inclusion, sparking nearly 160 riots across the country.

The contrast proved stark and uncomfortable: predominantly white, middle-class hippies rejected the material prosperity and social privileges their backgrounds afforded them, even as Black Americans struggled violently for access to those same opportunities.

Detroit witnessed one of the most devastating riots in American history that July, with 43 fatalities, 1,189 injuries, and roughly 2,000 buildings destroyed by fire or looting.

Detroit witnessed one of the most devastating riots in American history that July, with 43 fatalities, 1,189 injuries, and roughly 2,000 buildings destroyed by fire or looting.

Days earlier, Newark had endured five days of chaos that left 26 dead, over 700 injured, and entire city blocks reduced to rubble.

Chicago, Atlanta, New York City, and Boston joined the list of major urban centers consumed by unrest. Anti-war sentiment manifested in different forms across the region. Throughout October 1967, thousands of protesters clashed with police in Oakland, just across the bay from San Francisco’s peaceful gathering.

Anti-war sentiment manifested in different forms across the region. Throughout October 1967, thousands of protesters clashed with police in Oakland, just across the bay from San Francisco’s peaceful gathering.

Officers wielded clubs and deployed tear gas against demonstrators who opposed the Vietnam War, creating scenes of violence that contrasted sharply with the era’s rhetoric of love and peace.

Other protests took the form of teach-ins and peaceful marches, where activists educated the public about the war’s toll and advocated for change through nonviolent means.

As autumn arrived, the dream began to crumble. Police presence intensified throughout Haight-Ashbury, with law enforcement conducting frequent drug raids on neighborhood residences.

As autumn arrived, the dream began to crumble. Police presence intensified throughout Haight-Ashbury, with law enforcement conducting frequent drug raids on neighborhood residences.

Even members of the Grateful Dead, icons of the movement, faced arrest on drug possession charges. The idealistic hippies gradually departed, leaving behind a vacuum that harder elements quickly filled.

Dropouts and drug dealers replaced the flower children, transforming the once-vibrant neighborhood into a shadow of its former self.

The Summer of Love had ended, but its cultural impact would reverberate through American society for generations to come, reshaping attitudes toward authority, community, creativity, and consciousness in ways both profound and enduring.

(Photo credit: The black and white photos by Dennis L. Maness – dennismaness.net / Color photos via Flickr / Wikimedia Commons).